(10 min read) Albi Cathedral — number 27 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — showcases spectacular Late Gothic artistry in a monumental building intended to reassert the Church’s authority following the Albigensian Crusade.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Albi Cathedral

Official Name: Cathedrale Sainte-Cecile d’Albi (Cathedral of Saint Cecilia of Albi

Location: Albi, France

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1282-c1510

Why It’s Great

Albi Cathedral represents a fascinating synthesis of late Gothic architecture and early Renaissance decoration, creating one of Europe's most visually overwhelming sacred interiors through its extraordinary painted ceiling and intricate stone screens. Beyond its artistic achievement, the cathedral serves as a powerful architectural manifesto — its fortress-like exterior and sensuous interior decoration working together to reassert Catholic orthodoxy in a region still haunted by the brutal suppression of Cathar heresy.

Why It Matters: History and Context

The previous entry on Durham Cathedral showcased a Romanesque building with early Gothic overlays. This week’s entry examines the opposite end of the Gothic timeline — Albi Cathedral, a late Gothic structure whose interior is enlivened with the Renaissance-style paintings which cover almost every ceiling and wall surface (figures 1 & 3).

But to fully understand this church, especially its fortress-like appearance (figure 2) and the rationale behind its over-the-top interior, we need to first have a short digression about Catharism.

Sidebar: Catharism and the Albigensian Crusade

Catharism was a dualist Christian movement that flourished in southern France during the 12th and 13th centuries, particularly in the Languedoc region around Albi — hence the alternative name “Albigensian heresy.” Cathars believed in two opposing divine principles: a good God who created the spiritual realm, and an evil demiurge responsible for the material world. It’s essentially a form of Gnosticism, related to ancient movements like Manichaeism, which the Church had largely suppressed in late antiquity, but whose ideas continued to resurface in various forms throughout the medieval period.

This led them to reject the physical world as fundamentally corrupt, including the Catholic Church’s sacraments, clerical hierarchy, and emphasis on material wealth. They practiced extreme asceticism, rejected marriage and procreation, and believed that only through spiritual purification could souls escape the material prison. The movement attracted not only religious seekers but also local nobility who resented northern French political interference, making Catharism both a theological and political challenge to orthodox authority.

(Coincidentally, there’s an article from earlier this month over at Via Mediaevalis about the Cathars with much more detail, if you are interested.)

The Catholic Church’s response was swift and brutal. Pope Innocent III launched the Albigensian Crusade in 1209, promising the same indulgences offered to those fighting in the Holy Land. The twenty-year campaign devastated the region, culminating in infamous massacres like the one at Beziers, where Papal Legate Arnaud Amalric allegedly declared “Kill them all; God will recognize his own.” By 1229, the Treaty of Paris had effectively ended organized Cathar resistance, incorporating much of the Languedoc into the French crown and establishing the Inquisition to root out remaining heretics.

Albi Cathedral

It was against this backdrop of recent trauma and ongoing suspicion that Bishop Bernard de Castanet began construction of the new cathedral in 1282, replacing an earlier Romanesque structure. The timing was deliberate — the Church needed to reassert its authority in a region still recovering from the crusade’s devastation and the systematic elimination of its distinctive religious culture.

The cathedral’s design reflects this imperative. Rather than the soaring, light-filled spaces typical of High Gothic architecture, Albi presents an almost military appearance from the outside (figures 2, 4, 7-10). The massively thick brick walls — constructed from local red clay — rise without buttresses, their surfaces broken only by narrow windows placed high above ground level. The west’s single great tower, completed in the 1480s, dominates the skyline like a keep, while the original southern entrance portal (figure 4) resembles a fortress gate more than a traditional church front.

The builders created a structure that projected unassailable strength and permanence, a visual reminder that the Church had triumphed over heresy and would brook no further challenges to its authority.

The choice of brick, while partly an economizing practicality, also created a distinctly southern Gothic aesthetic that differentiated Albi (and much of Languedoc) from the limestone cathedrals of northern France.

Though the exterior projects defensive strength, the interior overwhelms through sensory abundance. Beginning in the late 15th century and continuing through the early 16th, the cathedral’s interior was transformed through an extraordinary decorative campaign that covered virtually every surface with paintings, sculptures, and ornamental work.

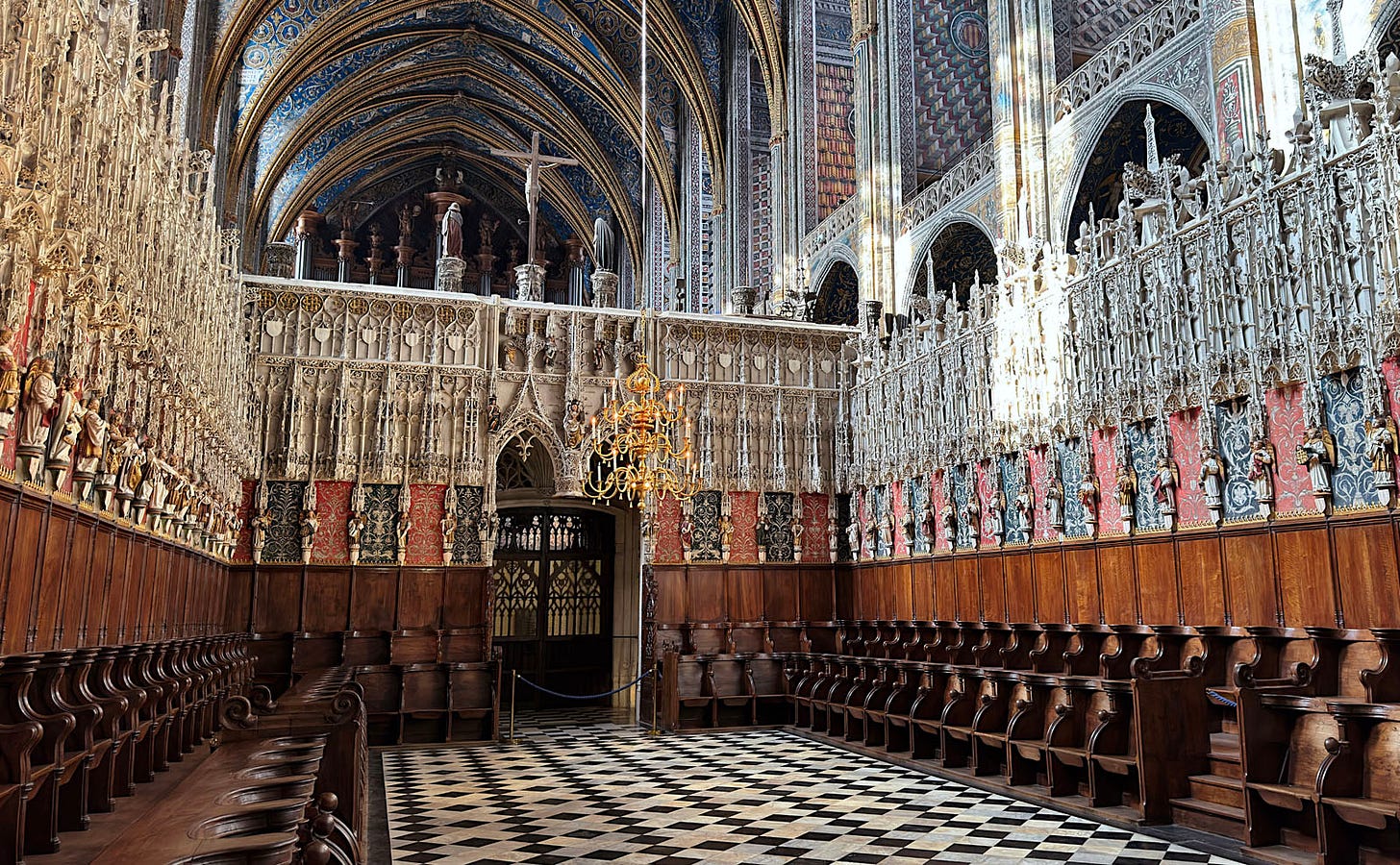

The cathedral’s interior is dominated by an extraordinary rood screen and choir enclosure, completed in the late 15th century. This elaborate stone screen system creates a church within a church, separating the choir from the nave while providing a dramatic backdrop for the liturgy.

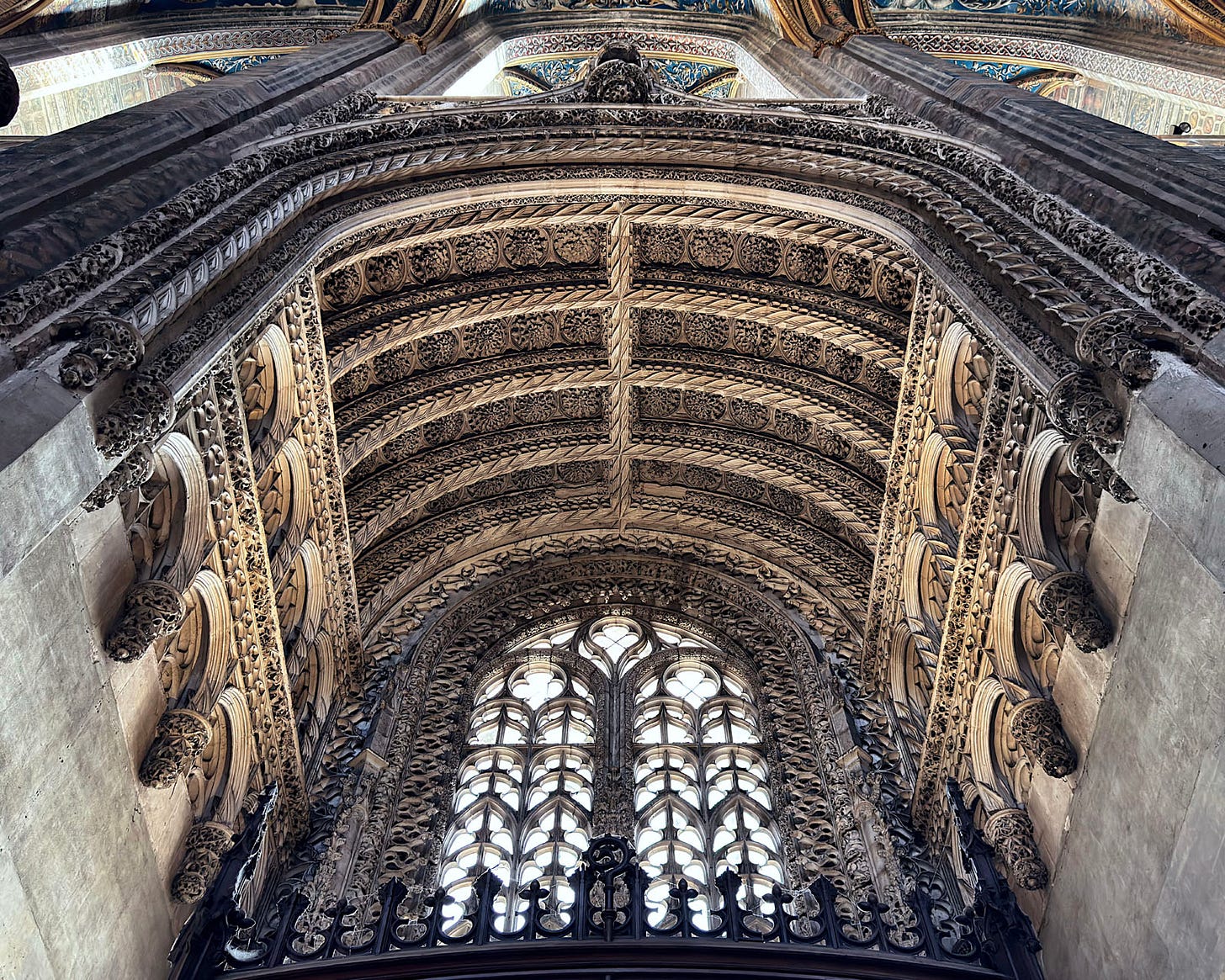

The rood screen itself — spanning the full width of the nave — is a masterpiece of Flamboyant Gothic stonework, its intricate tracery and sculptural program also wrapping around the entire chancel, creating an enclosed sanctuary that heightens the sense of sacred mystery.

While many French cathedrals lost their rood screens during later renovations, Albi’s survival provides a rare glimpse into how medieval cathedrals actually functioned liturgically, with their carefully orchestrated separation between clergy and laity.

This architectural framework would prove the perfect canvas for the painted decoration that followed, creating a unified artistic environment where Gothic structure and Renaissance ornament work together to overwhelming effect. The masterpiece of this program is the magnificent painted ceiling, completed between 1508 and 1512 by Italian and Flemish artists working in a Renaissance style. The vault displays an intricate program of biblical scenes, saints, and decorative motifs rendered in brilliant blues, reds, and gold. The walls received similar treatment, with painted architectural elements creating the illusion of carved stone tracery and sculpture.

This overwhelming decorative scheme served multiple purposes. Like the later Counter-Reformation artistic programs, it aimed to inspire awe and reinforce orthodox doctrine through visual splendor. But it also represented a deliberate rejection of Cathar antipathy toward material beauty — where the heretics had spurned worldly magnificence, the triumphant Church embraced it as a reflection of divine glory.

The cathedral survived the Wars of Religion relatively intact, though it lost some of its treasures during the Revolution. The 19th century brought controversial restoration work under architect César Daly, who added neo-Gothic elements to the exterior and restored much of the painted decoration — work that, while well-intentioned, has been criticized for its heavy-handed approach to the medieval fabric.

Today, Albi Cathedral stands as both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a powerful reminder of how architecture can serve ideological purposes.

Photo Tour

Albi Cathedral appears like a fortress as you approach it, and it is highly unusual in having no entrance on the west side — a trait it shares with Durham, by the way. Instead the entrance is on the south side, through an elaborately sculpted Flamboyant porch and portal (figure 10 and “In Detail” below) — a hint of what you will find inside.

Upon entering into the nave, the sensory overload is immediate — not through stained glass and light, as is typical for Gothic, but through brightly painted ceilings and walls and the elaborately carved rood screen that forms the eastern end of the nave (figures 5, 18-20, 24).

The west end of the nave has a late 15th century Last Judgement painted directly on the brick base of the west tower, below the organ (figure 12 and “In Detail” below).

Side chapels here are essentially carved into the thick brick walls, forming a series of niches between buttresses along the north and south sides, as well as around the eastern apsidal end (figures 13, 15-17, 21).

The rood screen, as mentioned above, was created in the late 15th century and the same style and workmanship extends behind it to surround the chancel. It is, in fact, primarily this screen and the spaces it encloses that make Albi Cathedral worthy of such a high ranking on the list — the detailed filigree is exquisite and much of the sculpture is original.

Figures 20-30 show the eastern end of the cathedral (along with several “In Detail” Notes below). First we explore the ambulatory, surrounded more side chapels on the exterior side and the carved screening on the interior.

The coup de grace, though, is the choir and high altar within the chancel — the inner sanctum where both the Mass and the Divine Office are celebrated — appropriately surrounded by a sensational series of sculptures and exquisitely detailed wall surfaces and ornamentation, as well as brightly colored ceilings (figures 25-29 & “In Detail” below).

The cathedral’s treasury (figure 30) is off the north ambulatory and features. Some of its holdings are shown in the “In Detail” section below:

In Detail

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 8 November 2024

It is free to enter the nave, but payment is required to pass from the rood screen into the ambulatory, chancel, and treasury. I do not recall the price, but — given the extradordinary beauty of those spaces — I am certain it is a bargain.

Albi Cathedral stands today as both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a powerful reminder of how architecture can serve ideological purposes. Its fortress-like exterior and sumptuous interior represent the Church’s determination to rebuild its authority through both intimidation and seduction — a strategy that would find fuller expression in the Counter-Reformation art and architecture of the following centuries.

This article is an absolute revelation. I had no idea that Albi Cathedral was so astonishing. I had seen pictures of it, but only showing thee rather forbidding and uninspiring fortress-like brick exterior. I've never seen the interior before. now very high on my list of places to visit - thank you Ben!

One of my personal favourites... It's difficult to convey with photographs just how stunning the exterior is in real life. The contrast between the weathered rose-coloured bricks and the severe 'modernist' shape of the building is very striking. And those shadows!