(8 min read) Durham Cathedral — number 28 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is one of Europe’s most interesting medieval buildings and represents an early stage in the transition from Romanesque to Gothic.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Durham Cathedral

Official Name: Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham

Location: Durham, UK

Primary Dates of (Romanesque &) Gothic Construction: 1093-1490

Why It’s Great

Durham Cathedral represents the crucial transition between Romanesque and Gothic architecture, featuring the world's earliest pointed transverse ribbed vaulting — a technical innovation that would become fundamental to all subsequent Gothic construction. The cathedral's remarkable architectural unity, combined with its pioneering structural achievements and dramatic hilltop setting, makes it one of Europe's most influential and aesthetically powerful medieval buildings.

Why It Matters: History and Context

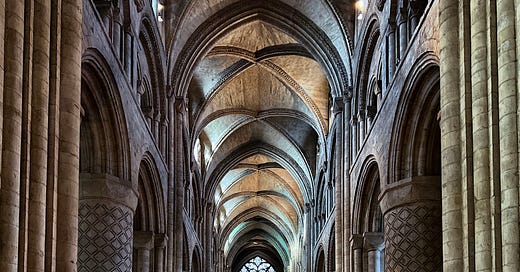

If this were a list of the world’s greatest cathedrals, regardless of style, Durham would appear much higher in my rankings. At the same time, the church is largely Romanesque (often called Norman in England), with just a few later Gothic additions and overlays, and a first look at the nave and choir (figure 2) might suggest that it is barely Gothic at all.

Look closely at the ceiling, however, and you will see the earliest pointed transverse ribbed vaulting in the world (figures 2 above and 3, 12-13 below). This was an important technical achievement made by the Norman builders here, and became two of the three key elements of Gothic architecture that would be brought together the influence the choir of St-Denis (see my essays “Two Short Histories” and “Evolution, Part I”) — and thus the shape of all future Gothic architecture.

Before the Norman Conquest, a succession of Saxon churches stood on this dramatic site above the River Wear, housing the shrine of St. Cuthbert since 995.

The current cathedral began construction in 1093 under the direction of Bishop William de St-Calais, just twenty-seven years after the Norman Conquest. The builders worked with remarkable speed and consistency of vision — the nave was completed by 1128, and the entire Romanesque structure was substantially finished by 1133. This forty-year construction period represents one of the most cohesive building campaigns of the medieval period, resulting in an architectural unity that few cathedrals can match.

The Norman architects and masons at Durham were innovators of the highest order. While the overall aesthetic remains thoroughly Romanesque — with its massive cylindrical piers, round arches, and geometric ornamentation — the builders here pioneered the pointed transverse ribbed vaulting that would become fundamental to Gothic architecture. This technical breakthrough, completed around 1100 in the choir and extended to the nave by 1135, preceded similar innovations at St-Denis by several decades. The Durham masons had discovered how to distribute the tremendous weight of a stone ceiling through a skeletal framework of ribs, allowing for both greater structural efficiency and the visual lightness that would define Gothic space.

Later in the twelfth century a Lady Chapel (now called the Galilee Chapel; figures 9-10) was added in a late Norman style, and at the end of the 12th century a cloister was added in an early Gothic style (figure 26).

The most significant Gothic addition came in the 13th century with the construction of the Chapel of the Nine Altars (figures 4 & 22-25), built between 1242 and 1280 to provide a more fitting eastern termination for St. Cuthbert's shrine. This Early English Gothic addition creates a dramatic contrast with the Norman work.

The western towers received their upper stages in the early 13th century, while the central tower (figures 6 & 15) was rebuilt in a later Gothic style around 1465-1490 after the original Norman tower showed signs of structural weakness. The Perpendicular Gothic design of this final tower, with its large windows and vertical emphasis, provides a fitting culmination to the cathedral's vertical composition.

Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, in 154, Durham's monastic community was disbanded, but the cathedral survived as a secular cathedral church.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw various “improvements” — including the insertion of classical fittings and the removal of medieval furnishings — that somewhat diminished its medieval character.

The Victorian period brought extensive restoration under George Gilbert Scott, who removed much of the Georgian work and attempted to return the building to its medieval appearance. While some of Scott's interventions were heavy-handed by today's standards, his work largely succeeded in restoring the cathedral's Romanesque grandeur.

The 20th and 21st centuries have seen more careful conservation efforts, including the ongoing preservation of the medieval stonework and the maintenance of this UNESCO World Heritage Site as both an active place of worship and one of Europe's most important architectural monuments.

Photo Tour

Whether because of the steeply sloping site or the relationship to the Castle to the north, Durham’s exterior is unusual in not having a proper west facade, and its main entrance (figures 7-8) are on the north side of the church, towards the westernmost end.

From the entrance, you first go into the Galilee Chapel (figures 9-10), a late Romanesque structure with remarkably slender columns and a wide open feel. The tomb of St Bede — “Father of English History” — is here (figure 10).

The Galilee Chapel leads to a tight narthex (figure 11), which was the original western end of the church before the Galilee Chapel was constructed.

The narthex opens into the massive nave (figures 2, 12-13), whose bays contain a wonderful alternating pattern of huge, chunky columns at ground level (see “In Detail” below for more) and slender composite columns which rise from the ground all the way up to the vault springs.

The crossing and transepts (figures 5, 14-17) continue the heavy Norman structure, though punctuated by larger Gothic windows and a late Gothic central tower.

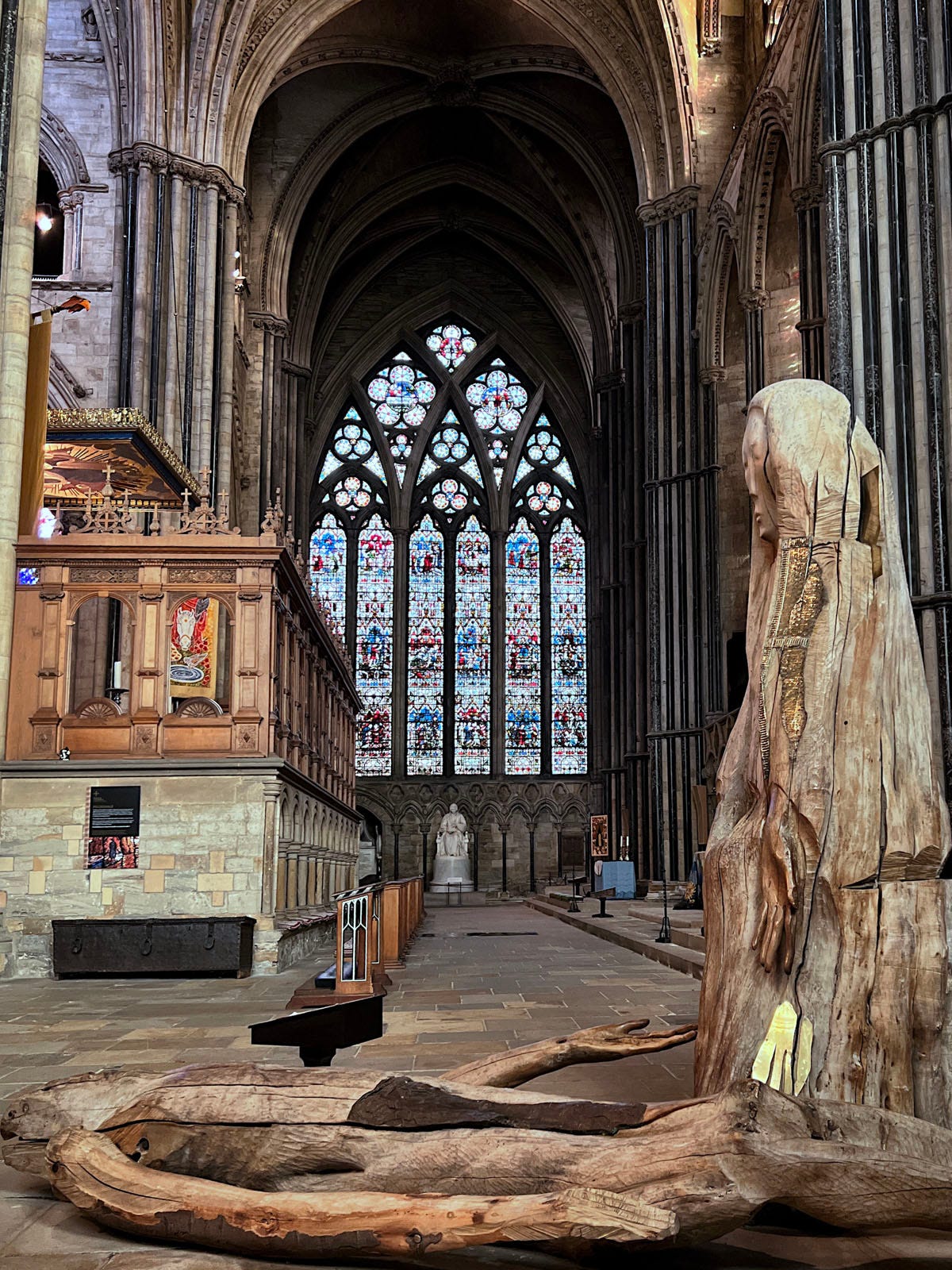

From the crossing you can pass through an open Gothic screen into the chancel (figures 18-21).

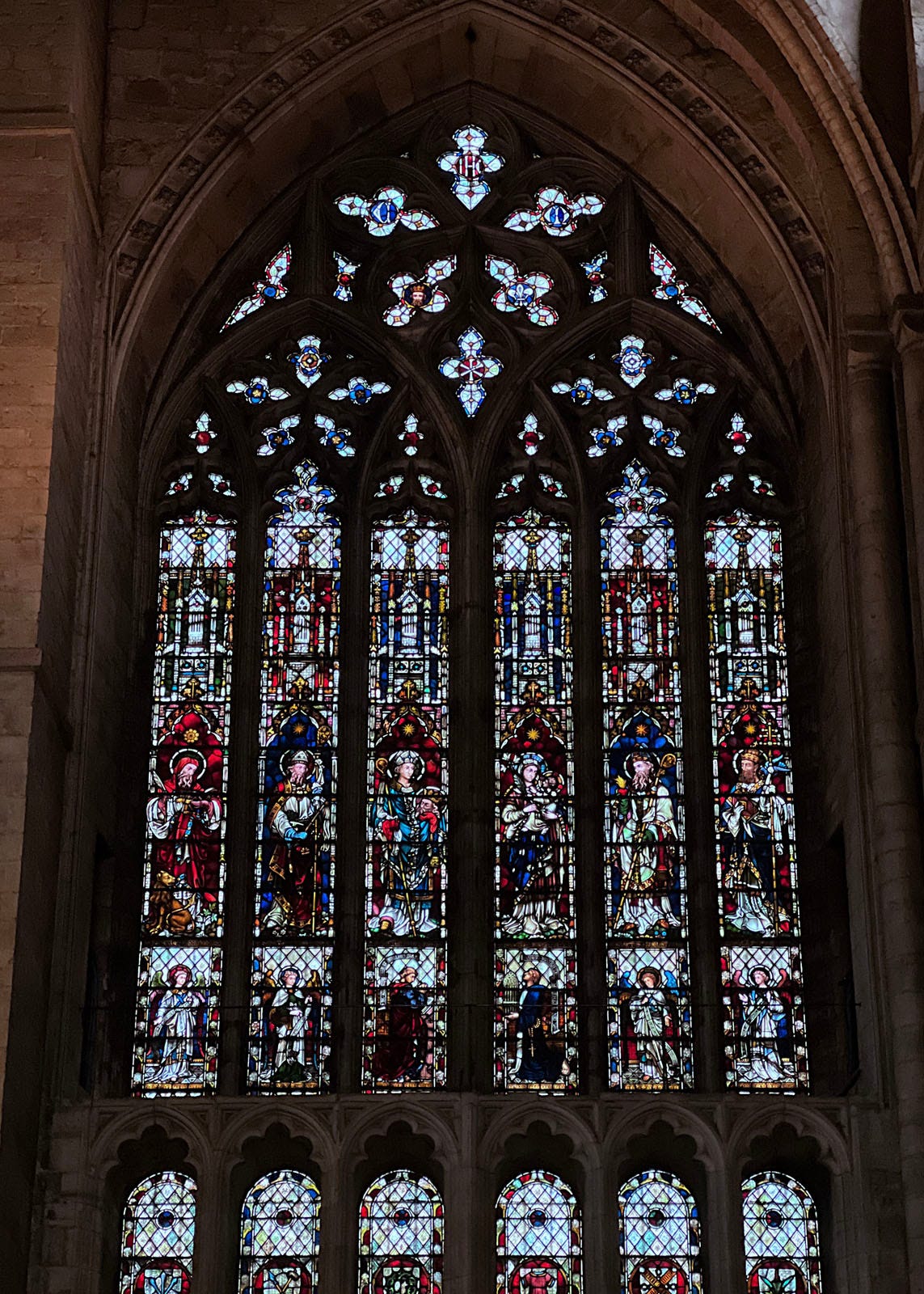

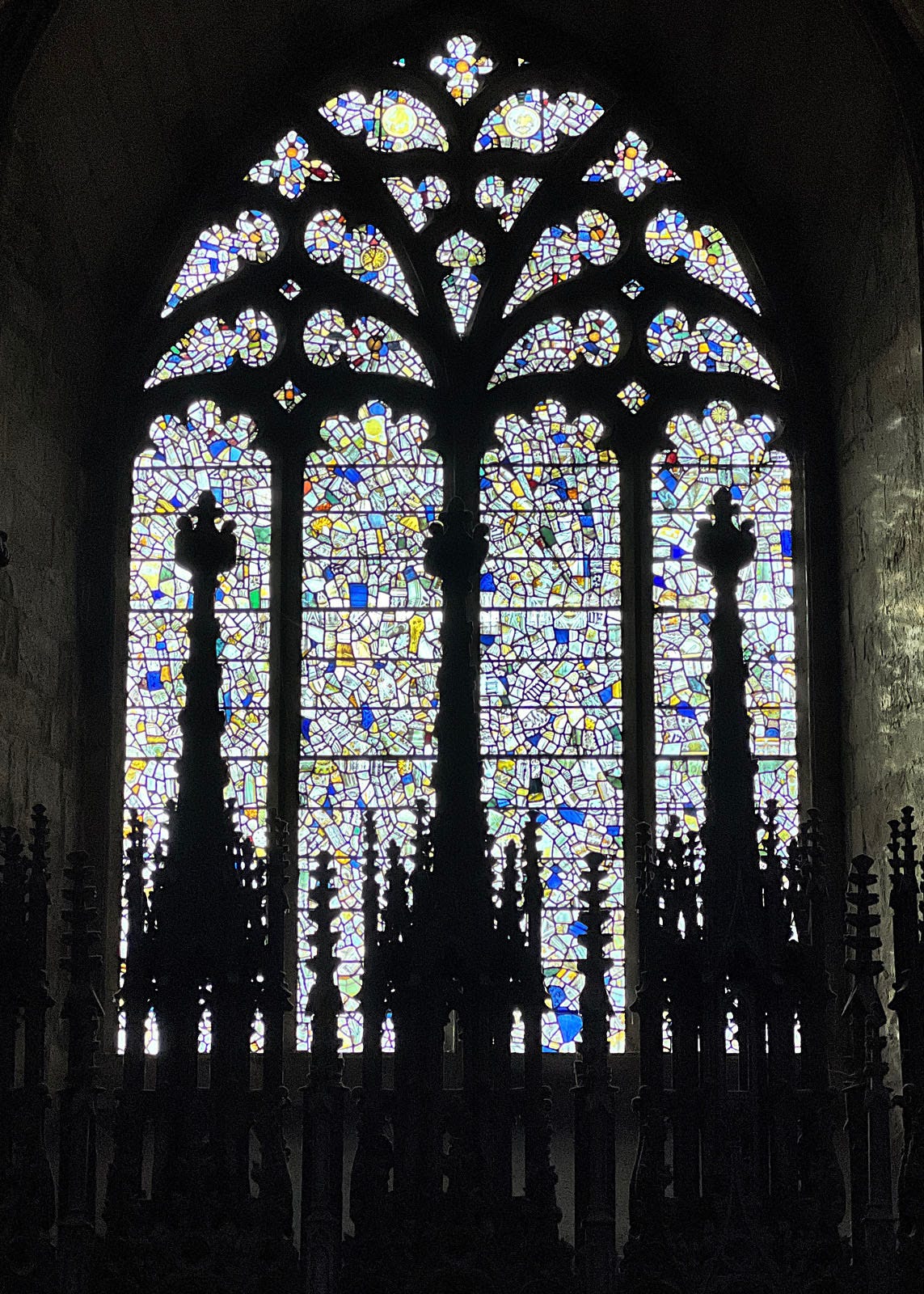

The Chapel of the Nine Altars (figures 22-25) forms the easternmost end of the cathedral and is the only truly Gothic portion of the cathedral. In addition to the Gothic architecture and windows, it contains several contemporary shrines, altars, and works of art.

To the south of the cathedral is the monastic complex (figures 26-27), several buildings of which now house a museum with artifacts from the cathedral and region (see “In Detail” below for more).

Figures 28-30 show various carved details at column capitals and spring points, as well as a stained glass window. I cannot recall exactly where any of these were located, so just enjoy them as isolated works of art.

In Detail

Here’s a Note featuring the great chunky columns in the nave, each bay featuring a different set of patterns:

Some of the artifacts on display in the on-site museum:

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 9 November 2022.

Durham Cathedral has ticketed entry. I do not recall if entering the m museum requires a separate ticket, but if so, I strongly recommend it.

Durham Cathedral stands as a testament to the innovative spirit that drove medieval architecture forward. While its massive Norman piers and round arches firmly root it in the Romanesque tradition, the pioneering ribbed vaulting overhead points toward the soaring Gothic cathedrals that would follow. This unique position — as both a masterpiece of Norman architecture and a crucial stepping stone to Gothic — secures Durham's place not just in my countdown, but in the broader story of how medieval builders learned to reach toward heaven with ever greater structural daring and visual grace.

You can see the powerful Norman Architecture in the structure. A power statement! Love it

I did wonder why you had ranked it so low until your reminder that you are ranking Gothic architecture and most of Durham is pre/proto-Gothic. Just ranking cathedrals, it would probably hit my top 5.