(13 min read) A visual essay tracing the many lives of the unicorn across medieval Europe — from fantastical beast to erotic allegory, from royal heraldry to sacred symbol.

Real unicorn horns were rare in the Middle Ages, but not unheard of. For example, on feast days two of them (figure 2) would be placed on the high altar of Utrecht’s Mariakirche as a symbol of the Virgin’s chastity.

Rudolph II — the alchemically-inclined Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor who surrounded himself with wonders mechanical and natural in Prague Castle — had a scepter made from one, which can now be seen in Vienna’s Imperial Treasury (figure 3).

Unicorn horns were useful as well. They could purify water, and in powdered form neutralize poison and cure disease. So even in the 18th century a unicorn horn could still appear on a pharmacy sign — affixed to a carved horse’s head in Bavaria (figure 4).

Origins

The unicorn may feel like a quintessentially medieval invention, but the impulse to imagine horned or hybrid beasts is far older — and strikingly global. Among the earliest known depictions of such animals are the so-called “unicorn seals” of the Harappan civilization (figure 5), dating to the third millennium BCE.

While these images likely portray stylized versions of real animals, they were carved in profile, often with only a single horn visible and have become knows as “unicorn seals.” In the same period, sculpted figures like the terracotta rhino (also figure 5) show the Harappans were intimately familiar with the region’s large, horned fauna.

Such early works, as well as references by ancient Greek and Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder, show that the unicorn emerged from a cross-cultural, ancient tradition of stylizing and sacralizing powerful, elusive animals.

By the early Middle Ages, unicorns had begun to surface in the visual culture of Europe — not yet frequent, but present. A remarkable example is a carved ivory oliphant made in southern Italy and gifted to York Minster in 1030 (figure 6). Drawing on Near Eastern and Islamic motifs, this horn features a composite beast with a clear, singular frontal horn — surrounded by other chimeric animals.

By the 12th century, unicorns appear more clearly in manuscripts, especially bestiaries, which mingled animal lore with moral allegory. The Aberdeen and Ashmole Bestiaries (figure 7) both contain vivid illustrations of the unicorn, and the latter shows an early version of the “unicorn hunt” in which a beast can be tamed only by a virgin, and which hunters capture through her guileless charm.

In a misericord from Lausanne Cathedral (figure 8), carved around the same time those bestiaries were made, a knight battles a unicorn like any other monstrous beast — not an allegory of purity, but a test of martial skill. It’s a reminder that before the unicorn was domesticated by courtly love or elevated into Marian iconography (as we will soon discuss) it remained wild, ambivalent, and strange: part of a larger medieval fascination with creatures at the edge of the known world.

In Popular & Chivalric Culture

To understand the unicorn’s place in the medieval imagination, one must begin in the court, where the unicorn became a fixture in chivalric romance. They shared conceptual space with wildmen, dragons, lions, lovers, and ladies-in-gardens — icons for a social elite obsessed with taming the untamable, whether in war, in love, or within themselves.

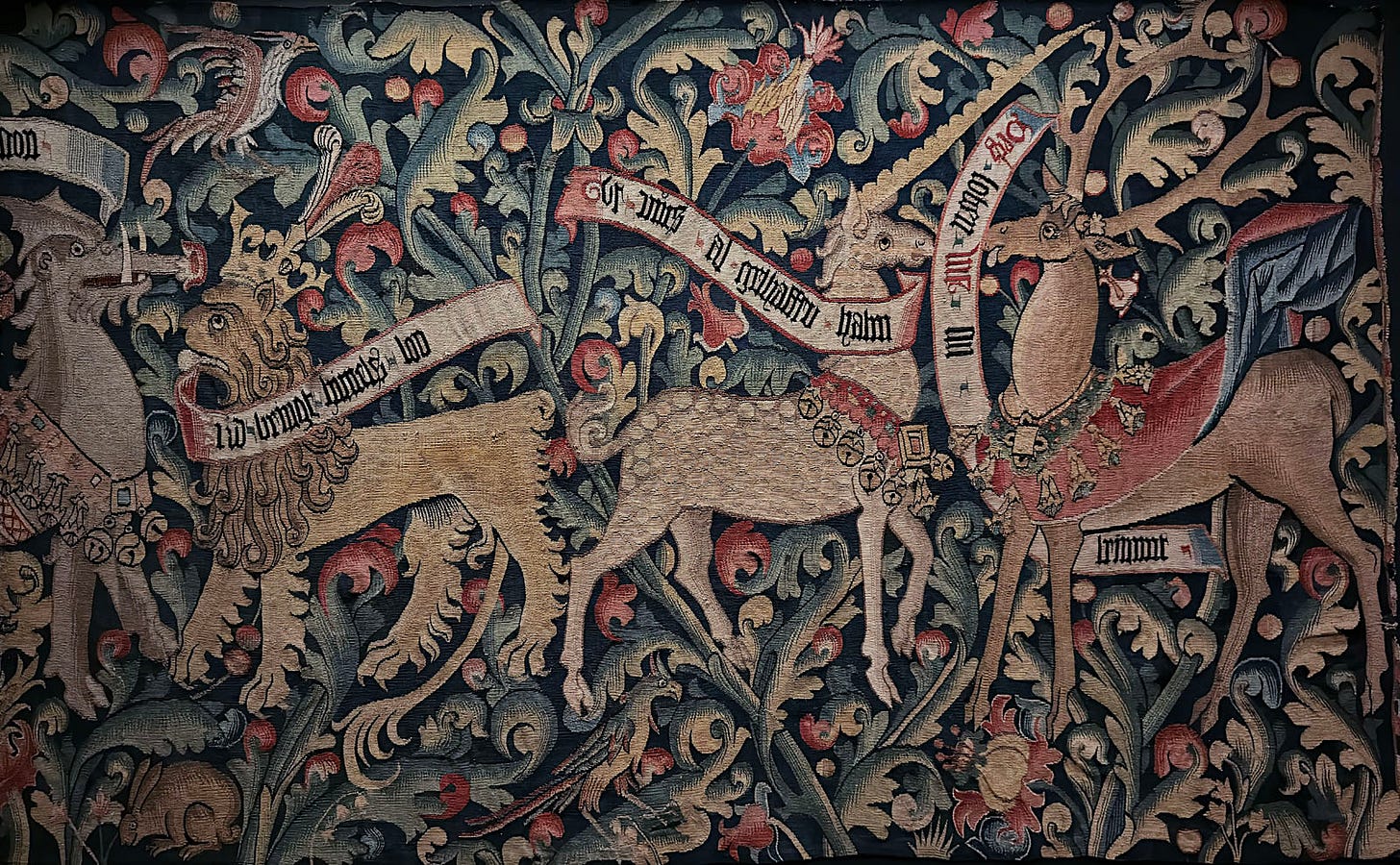

In many tapestries of the period, unicorns appear among both real and fantastic animals. In a woven scene from Basel (figure 9), they share a crowded pictorial field with lions, stags, and other hybrid beasts, suggesting that the unicorn was no longer an exotic anomaly but a naturalized part of the imagined menagerie. By contrast, in a mille-fleurs tapestry from Hainault (figure 10), the unicorn lounges in a flowering field, aloof but unmistakable — a courtly version of Eden’s innocence.

By the late Middle Ages, unicorns were not only familiar — they had become entangled in the erotic imagination.

In a tapestry from Basel (figure 11), a young woman reaches forward and caresses the unicorn’s horn with deliberate intimacy, while the unicorn bows slightly. The eroticism is hard to miss. The unicorn, here, is a proxy for desire itself — held but not yet consumed.

A tapestry from Strasbourg offers a broader — and rowdier — fantasy. In “The Wildfolk Storming the Castle of Love” (figure 12), wildmen attack a garden of noblewomen while riding an entire bestiary of leering mounts. The scene is absurd and theatrical, but unmistakably erotic in tone. One of the attackers straddles a unicorn, which has become not a sign of chastity but a vehicle for lust. These images were popular precisely because they were outrageous — a courtly inversion of virtue, performed with a wink. The unicorn plays along, quite literally carrying the charge — and with a flower it his horn’s/charge’s tip.

Yet not all unicorn scenes are so chaotic. In another tapestry from Basel (figure 13), the tone shifts to courtly devotion. A man presents a flower to a woman beneath a tree; a unicorn waits patiently nearby. The presence of a monkey suggests mischief, but this scene is controlled, idealized. It’s no longer about physical contact or siege — it’s about vows, restraint, and symbolic fidelity. The unicorn has gone from object of erotic fantasy to witness of courtly order.

“The Triumph of Chastity” (figure 14) points towards the role unicorns played as a symbol of purity and eventually religious devotion,. In this monumental allegory, unicorns draw the chariot of Virtue across a field of floral emblems and noble onlookers. The message is clear: desire, once wild, has been sublimated. The unicorn has completed its journey — from hunted beast, to lover’s double, to beast of burden in the service of purity.

Virgin & Unicorn

By the late Middle Ages, the unicorn had not only been moralized, but sacramentalized. In the “Virgin & Unicorn” motif — one of the most enduring and iconic pairings in medieval visual culture — the beast becomes a creature of stillness, no longer wild or even courtly, but spiritually tamed. Almost invariably, the unicorn is shown curled beside a seated woman, often nestled into her lap.

Across Europe, from Spain to Zurich to Cologne, the composition repeats with minor variations. The cushion cover from Cologne (figure 15), the carved convent panel (figure 16), the Toledo misericord (figure 17), and the stove tile from Zurich (figure 18) all depict the same essential idea: that purity draws power to itself — not through force or conquest but through virtue.

But the motif was more than decorative repetition. It was an emotional theology, encoded in image: the virgin is not just any woman, and the unicorn is not just any beast. What could be a story about seduction — or even trap — can also be a scene of mystical peace. In this context, the unicorn no longer signifies danger or desire, but grace accepted.

On the tomb of Renée d’Orléans-Longueville (figure 19 & “In Detail” below), a unicorn lies faithfully at her feet — replacing the lions, dogs, and dragons that typically appear at the base of funerary effigies. Here the unicorn is not only her companion but her emblem. It tells us who she was — or more precisely, how she was to be remembered: as chaste, noble, and untouchably pure. In a tomb like this, the unicorn becomes the quiet guardian of memory.

Religious Allegory

By the fifteenth century, the unicorn had crossed fully into sacred iconography. Its symbolic power was now redirected toward religious mystery, and most especially toward Christian ideas of purity and incarnation.

In figure 20, we see an especially subtle variation: a statue of St. Barbara adorned with a unicorn pendant at her throat, as a sign of chastity.

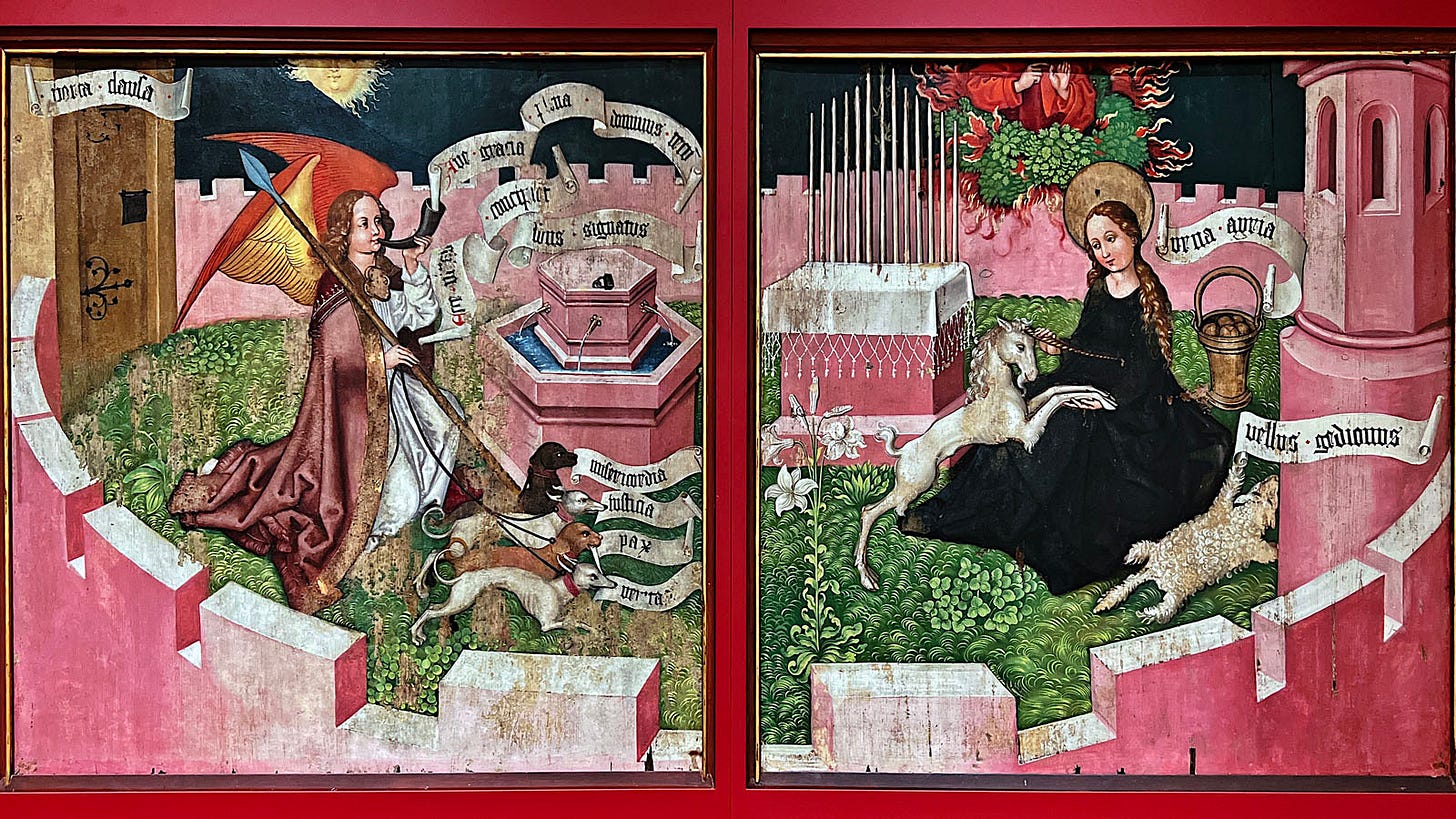

It was in Annunciation imagery (figures 1, 21-23), however, that the unicorn’s spiritual role reached its fullest expression. In this context, the unicorn is not simply with the Virgin — it is the Christ himself, arriving in her garden like the hunted beast of bestiary lore, not fleeing but submitting. In the Basel tapestry shown in figures 22 & 23, the symbolism is clearest. Here, the unicorn has arrived — and in the detail we see it being pierced by a spear, its blood flowing into a chalice. This “blood pouring int o a chalice” is common iconography in Crucifixion scenes, and nothing short of a visual Eucharist.

That sacrificial symbolism reappears, more abstractly, in The Redemption of Man (figure 24 & “In Detail” below), a grand tapestry combining allegory, liturgy, and apocalyptic narrative. Below a Crucifixion scene, the unicorn stands among the personified Virtues as they battle the Vices — its horn aimed directly at the crucified Christ. The geometry of the scene is unmistakable: the unicorn, once a hunted beast, now points unambiguously to the redeemer.

Even in quieter works, the unicorn remained an animal of the sacred threshold. In a panel from the Cluny Museum (figure 25), we see the unicorn among a curious host of protective beasts— lion, porcupine, stag — who stand vigil over the dead body of St. Stephen, Christianity’s first martyr.

Elite Culture

The unicorn was never simply a theological symbol or romantic metaphor — it was also a marker of status. In the courts of late medieval Europe, it signified not just purity, but privilege. Its association with the hunt — a pastime reserved for the aristocracy — reinforced this link. Like the Grail quest, the hunt for the unicorn was understood not merely as sport, but as ordeal: a symbolic pursuit of the unattainable, the divine cloaked in the wild.

In this context, even utilitarian objects became vehicles of myth. The unicorn-shaped aquamanile from Nuremberg (figure 26), a vessel for washing hands during meals, would have been used in elite banquets — a ritual of cleanliness made symbolically resonant by the beast’s purifying connotations. One purified one’s hands with the unicorn’s waters, so to speak.

By the late Middle Ages, the unicorn had become more than an allegorical beast — it was a heraldic statement, adopted by elites who saw in its layered meanings a fitting mirror for their own status. Purity, yes — but also power, rarity, and divine legitimacy. In this context, the unicorn moved beyond tapestries and altarpieces and entered stone and shield, as you can see in the heraldry for Louis Gruuthuse (figure 27) and James V of Scotland (figure 28).

Persistence & Re-Enchantment

With the rise of modern thought, the unicorn faded into fantasy. Yet it never disappeared; instead, it endured — first as dynastic emblem, then as romantic symbol, and finally as something closer to a psychological archetype. When Scotland joined with England, the unicorn remained — its place in the Royal Arms of the United Kingdom (figure 29) is not accidental.

The unicorn remains a staple of fantasy and childhood up into the 21st century. These later incarnations are outside the scope of this essay, but I will still share a painting by Gustave Moreau, whose work you might know I adore. In the unfinished painting of figure 30, Moreau shows his mastery of symbolism — there is not just a comely partial nude next to the unicorn, but the unicorn is wearing a pendant of coral, and coral was in medieval times a common symbol for the Christ, just as the unicorn itself was.

Across more than a millennium of European art and thought, the unicorn has shape-shifted from wild chimera to devotional emblem, from courtly fantasy to sovereign beast. It has been hunted, tamed, adored, allegorized, and institutionalized — yet never quite explained away.

Its power lies perhaps in its slipperiness: whether curled in a virgin’s lap, pulling the chariot of Chastity, or gazing out from the dreamscapes of a Symbolist painter, the unicorn has long marked the place where desire, purity, and the impossible meet.

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

In Detail

Here are some detailed looks at a few of the artworks above, presented in rough chronological order of creation:

Enjoyed this very much. The images I know best are the late 15th century tapestries in the Cloisters in NYC. I will see them with new eyes.

Great article, Ben, thank you! You mentioned Scotland and Bruges so I was surprised that you skipped the Scottish Order of the Unicorn, for which the only extant example is in a glass window portrait of Anselm Adornes at the Jeruzalemkerk in Bruges. I feel like an idiot for not knowing how to add a picture to this comment, but I found an article you may find interesting in this regard:

https://www.the-low-countries.com/article/anselm-adornes-brought-the-holy-land-to-bruges/