(7 min read) Tours Cathedral — number 34 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — synthesizes a wide range of Gothic styles with exceptional unity and grace.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Tours Cathedral

Official Name: Cathédrale Saint-Gatien de Tours (Cathedral of Saint Gatianus of Tours)

Location: Tours, France

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1170-1547

Why It’s Great

Built over nearly four centuries, Tours Cathedral contains the full gamut of French Gothic styles — from late Romanesque to Flamboyant, even edging into Renaissance. But unlike many cathedrals built over a similar duration (eg, Ely), it achieves a rare stylistic unity. Nothing feels stitched together: the proportions are balanced, the rhythm is steady, and the transitions are seamless.

Achieving such architectural coherence across such a long timespan is its quiet triumph. Add to that one of the finest ensembles of 13th-century stained glass in France, and you have a cathedral that rewards both the sweeping view and and close study.

Why It Matters: History and Context

Tours Cathedral is a rare example of Gothic architecture that was realized over four centuries without losing its compositional clarity.

Construction began around 1170, following a devastating fire that destroyed the earlier Romanesque cathedral. That fire, set during one of the many flare-ups between Henry II of England and Louis VII of France, didn’t just clear the ground — it reset the architectural ambitions of the city. What followed was one of the most prolonged and layered cathedral projects in France.

Work began with both the west towers and at the eastern end, with the chevet and choir laid out in the early 13th century.

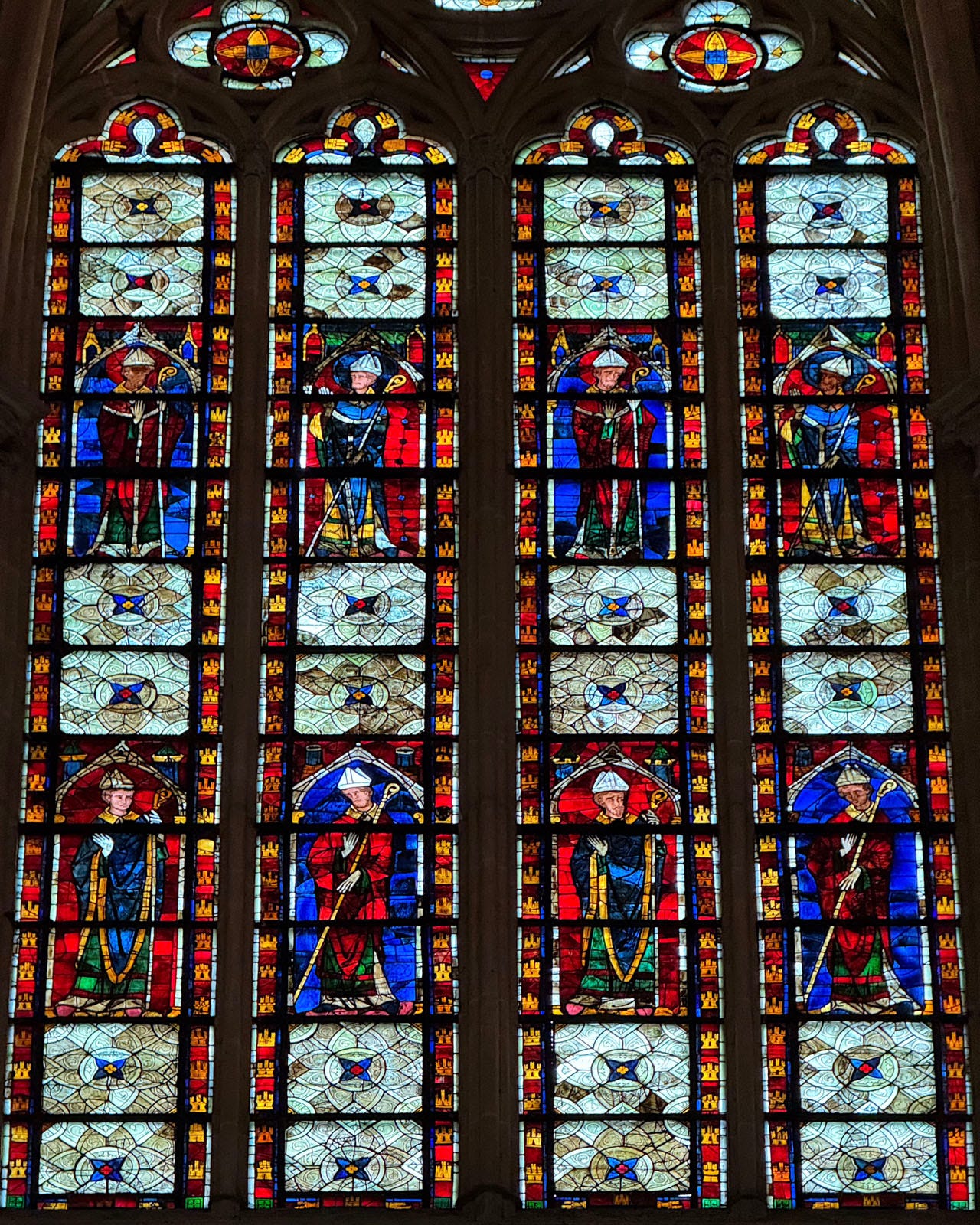

The east end is pure High Gothic: soaring arcades, slender shafts, and luminous clerestory windows. The ambulatory and radiating chapels — home to some of the best-preserved 13th-century stained glass in Europe — set the tone not only for Tours but for the whole Loire Valley.

The transept came next, around the early 14th century, followed by an agonizingly slow westward crawl of the nave. Delays were frequent — wars, plagues, economic downturns, shifting political patronage — and yet the building campaign never entirely stalled.

Remarkably, as the project evolved, the builders didn’t veer off into an assemblage of distinctly different parts and pieces. Instead, they adapted: adding Flamboyant details in the 15th century without disrupting the earlier massing and rhythms. They capped it all in the 16th century with a western facade and twin towers that reach from Flamboyant Gothic overlays on a Romanesque base at the bottom, to an almost proto-Baroque top.

By the time the final stone was laid in 1547, the Renaissance had already arrived in the Loire Valley. You can see it in the very tops of the towers — delicate pilasters, classical motifs — a clear departure from the Gothic vocabulary below. And yet somehow it all coheres.

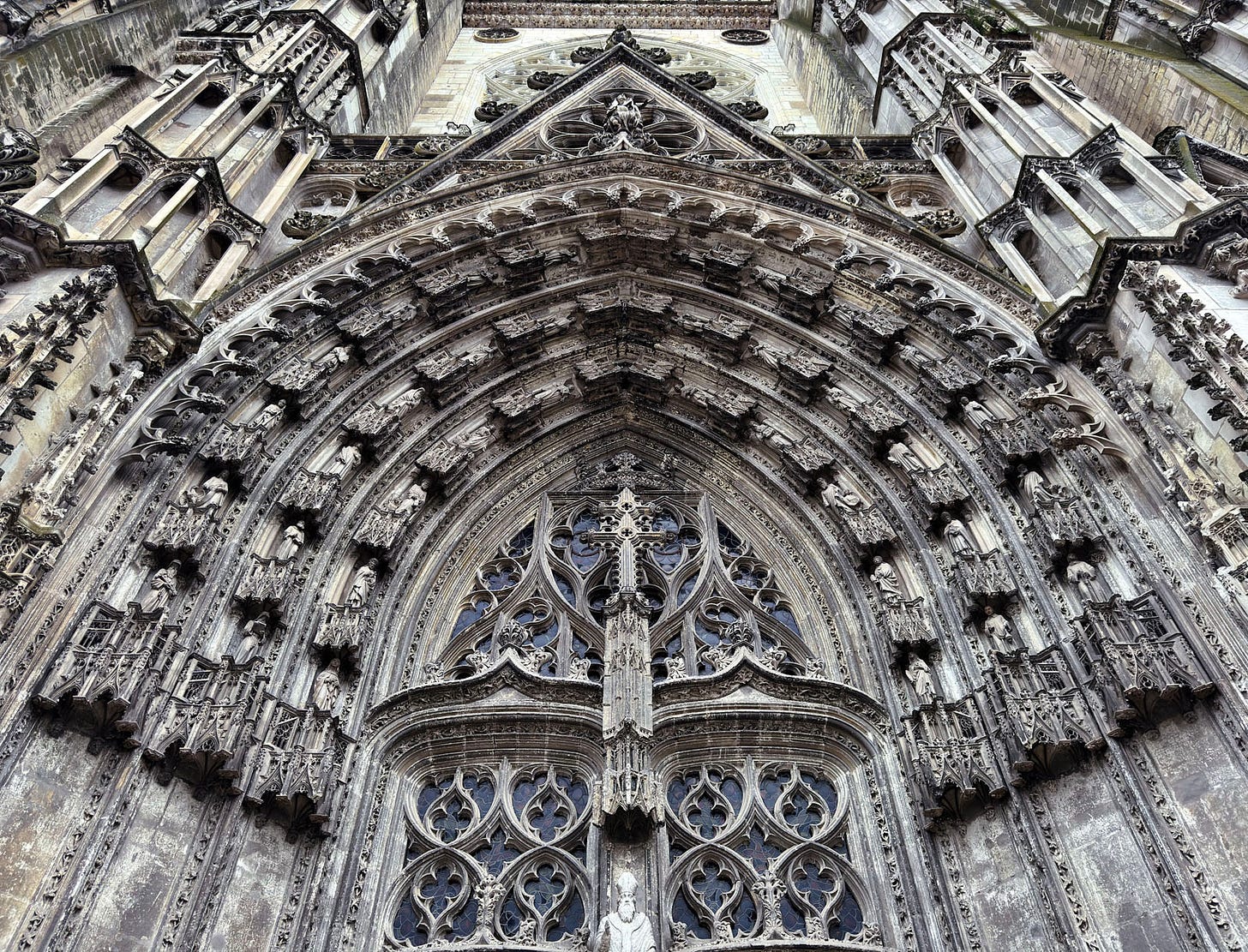

Historical forces continued to shape the building after completion. During the Wars of Religion, Protestant forces sacked the cathedral, smashing much of the facade sculpture. The damage is still visible: niches stand empty, heads are gone. And yet the structure held. And remarkably much of the medieval stained glass was spared.

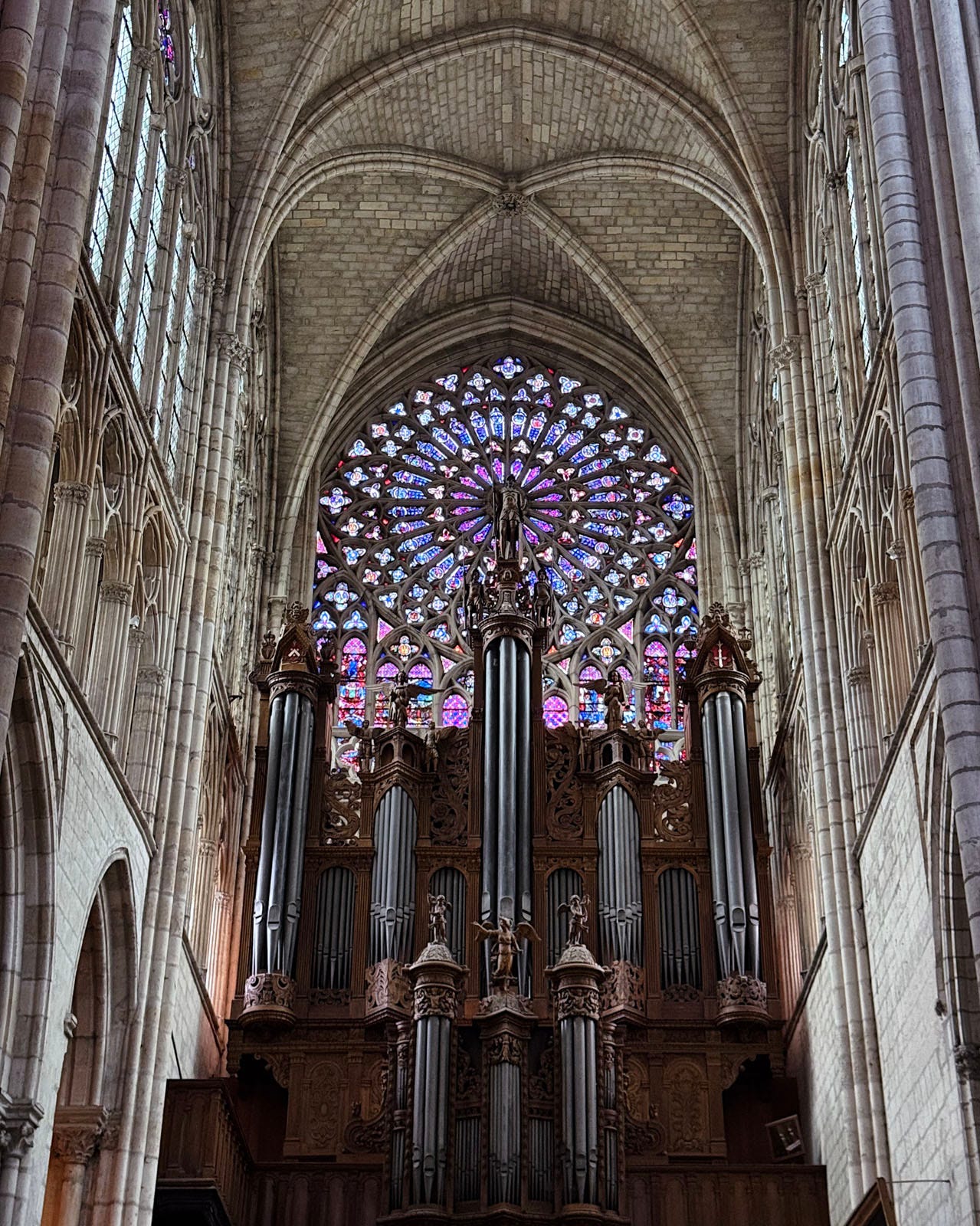

In the 17th and 18th centuries, minor additions and restorations were made — new organs, chapels, and furnishings — but the Gothic fabric remained largely untouched. During the Revolution, the building was de-Christianized but spared destruction, and in the 19th and 20th centuries, it underwent restoration without the overzealous interventions that plagued some of its peers.

Tours shows how a cathedral can grow slowly, absorb centuries, and still emerge as a unified whole. It’s not just a record of Gothic style — it’s a meditation on continuity.

Photo Tour

Figures 8-11 show the east and southern sides of the cathedral. The eastern end of Tours Cathedral reveals the elegance of its early Gothic design. The chevet, ambulatory, and radiating chapels form a clean, cohesive ensemble characteristic of the 13th century’s High Gothic.

The flying buttresses really stand out here, especially at the south transept the cathedral’s supports for the south transept they leap across the narrow street, tying into adjacent structures. This is a visible reminder of how the medieval city and cathedral were entangled — spiritually, socially, and even physically.

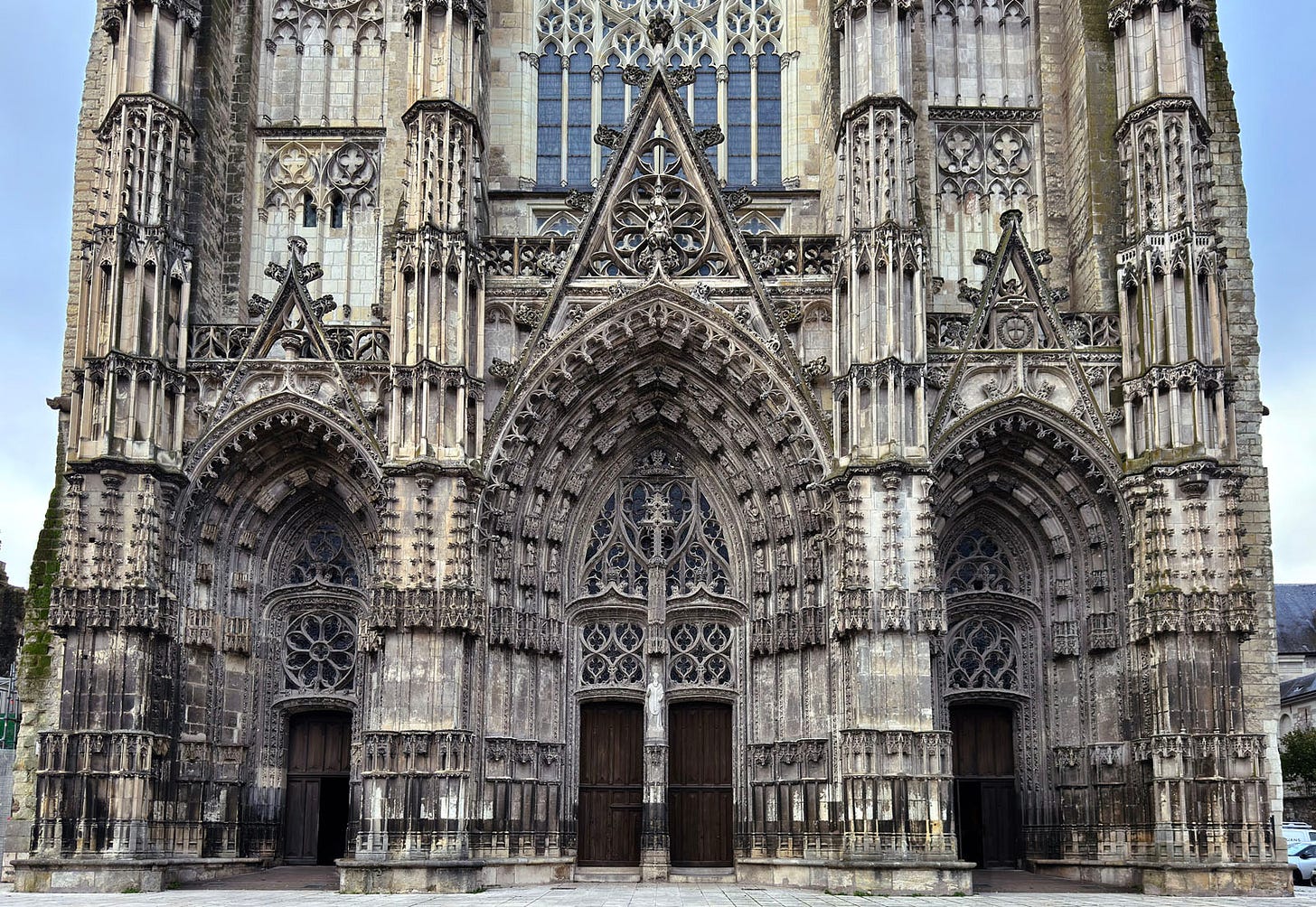

The west facade (figures 3, 6 & 12-13) is one of the last great Gothic facades created in France, and also one of the most architecturally peculiar. Its Flamboyant tracery and ornament don’t simply cover the surface — they seem to animate it, with filigreed forms thrusting upward. Vertical acceleration is amplified by the towers, which begin as solid Romanesque volumes and end — nearly four centuries later — with delicately layered Renaissance crowns.

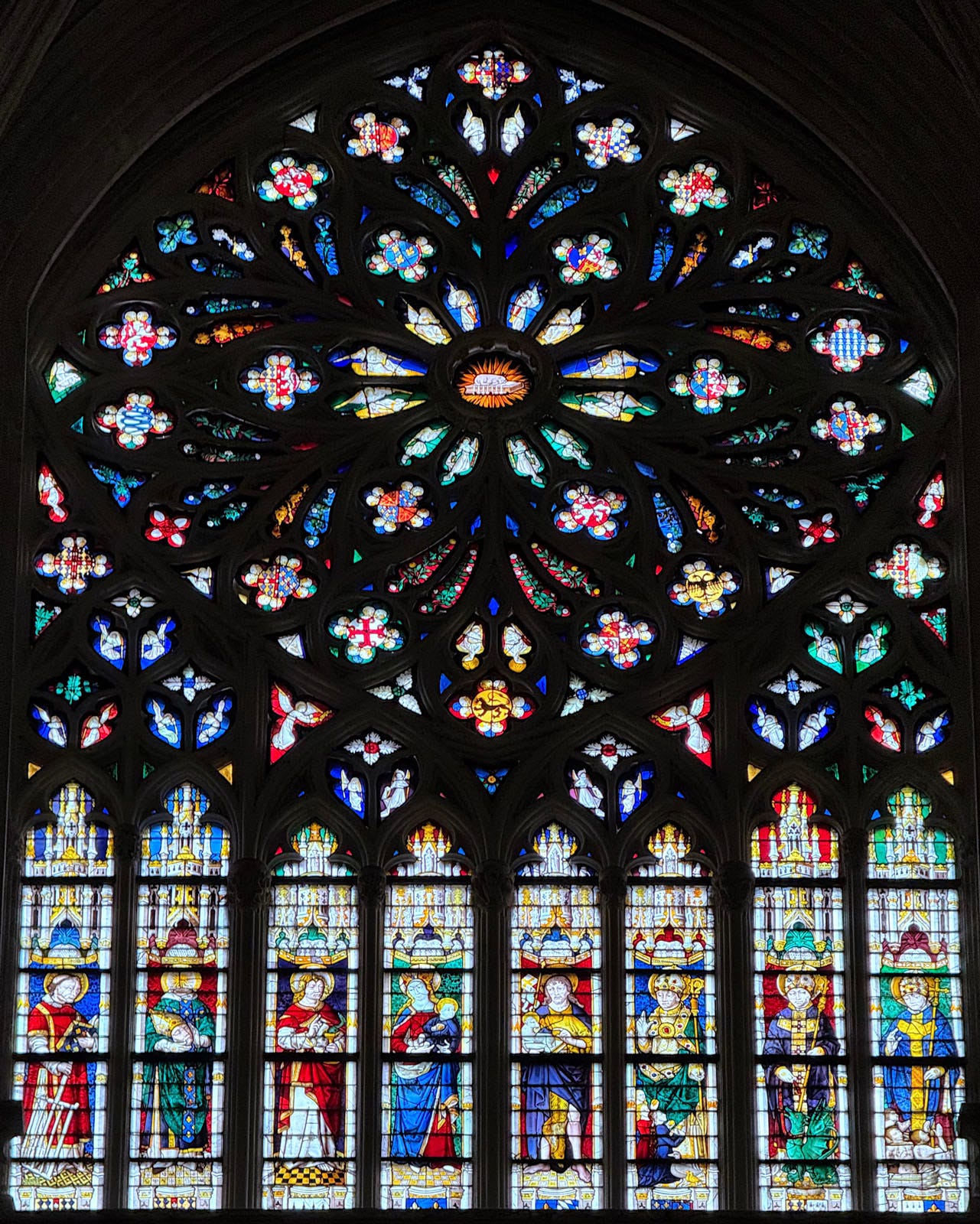

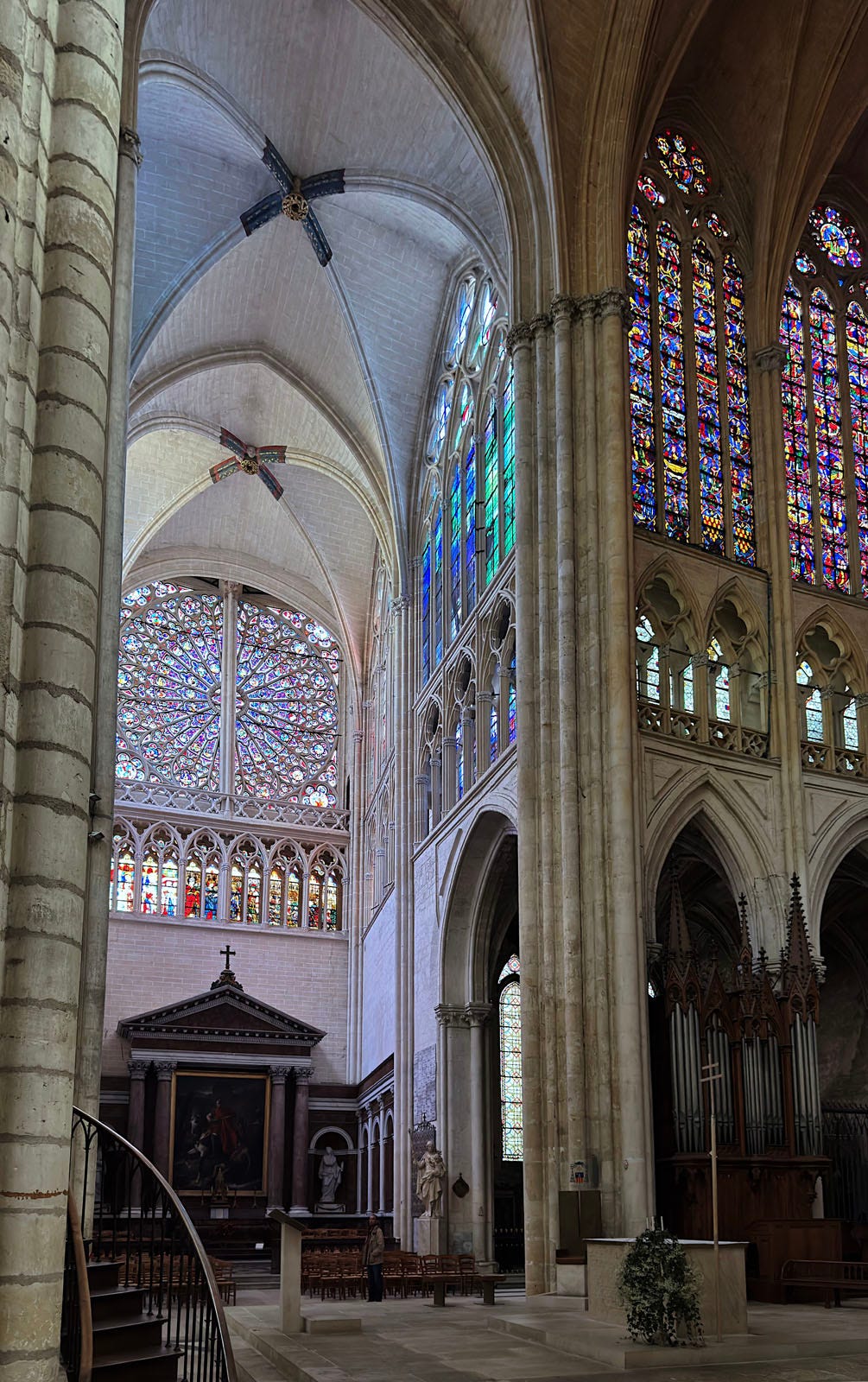

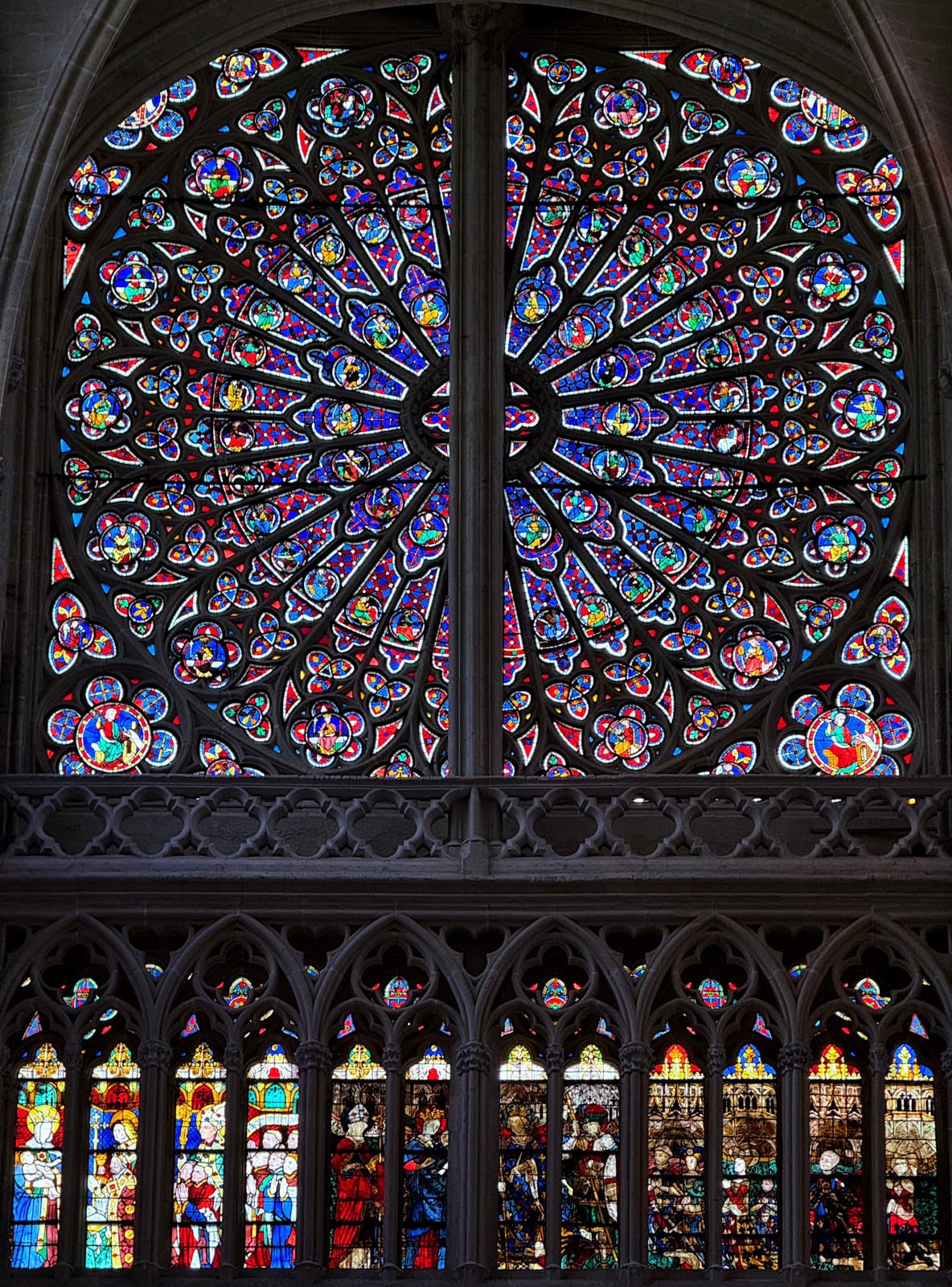

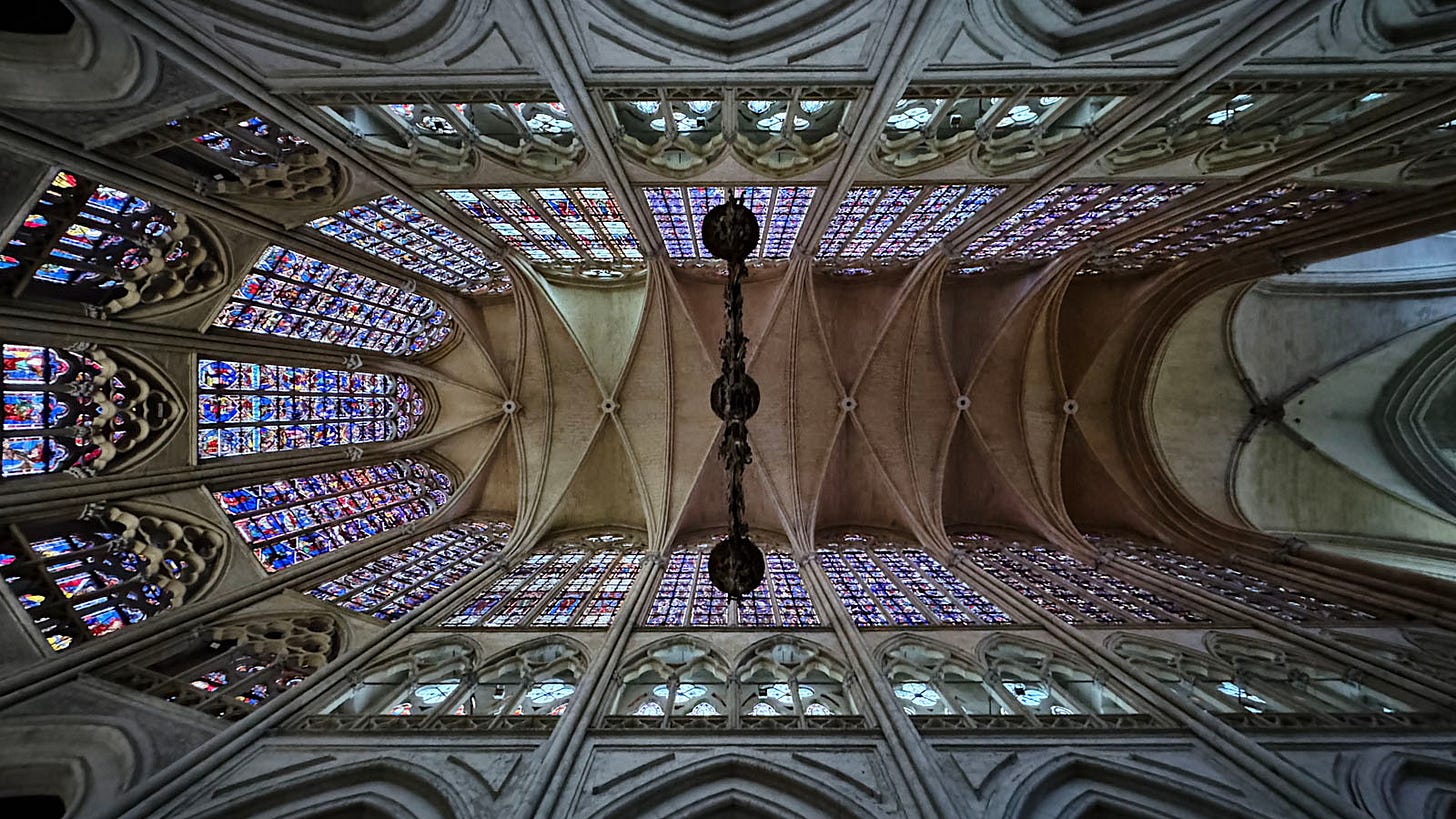

The nave (figures 14-17) is a clean example of late Gothic interior rhythm. It’s long, high, and harmonious, which is especially remarkable given how long it took to complete. While construction began eastward in the 13th century, the nave took shape mostly in the 15th. The west rose window, above the central doors, is late — probably mid-15th century — and bears the hallmarks of that era’s expressive tracery.

Figures 4, 7, & 18-20 focus on the transepts and crossing. The crossing of Tours Cathedral is where the layered timeline becomes most legible. Standing beneath it, you feel the convergence of different centuries — the Early Gothic forms below giving way to increasingly ornate vaulting and decorative programs overhead. The north and south transepts each have their own flavor. The north, slightly later, is more intricate, while the south retains more of the plain, early 13th-century massing.

The chancel and apse (figures 1 & 2, 21-26) were the heart of the early Gothic campaign — begun in the 1220s and completed by the mid-13th century.

The clerestory and triforium windows of the chancel (detailed in figures 24-25) are remarkable examples of medieval glass:

The ambulatory and radiating side chapels are shown in figures 27-29, and there are also detailed Notes embedded the in “In Detail” section below featuring detailed looks at some of the medieval stained glass panels in the side chapels here.

In Detail

Here are two notes, each featuring pictures of some of the stained glass in two different side chapels off the ambulatory

~

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 5 November 2024

Tours Cathedral is open daily and free to enter. Late morning or late afternoon gives you the best light for the stained glass, and the place seems to be relatively under-visited, so no need to time a visit based on crowds.

Tours Cathedral doesn’t have the scale or drama of the French cathedrals at the top of my list. What it offers instead is continuity —a four-century commitment to balance, beauty, and compositional clarity.

I visited here about 20 years ago before I had any understanding of what I was looking at. I was in Tours to visit Chambord etc. and happened to pass the cathedral and pop in. I remember being struck by the height (although nothing like as high as many of the other French cathedrals) and the simplicity - probably what you describe as the unified nature of it.

I went at night. The silence was defeaning. The silhouettes of the towers in the dark of night is terrifying. Fond memories!