(9 min read) Seville Cathedral — number 24 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is a massive complex built when Spain was on the verge of becoming the first empire “on which the sun never sets.”

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Seville Cathedral

Official Name: Catedral de Santa María de la Sede (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See)

Location: Seville, Spain

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1401-1519

Why It’s Great

Seville Cathedral is the largest Gothic cathedral in the world (by volume), and its construction spans from the early 15th to late 16th centuries — a period during which the city became the heart of the first worldwide imperial power. Built on the remains of a mosque, and with gold and silver coming in from the New World, the massive complex showcases the city’s ambition with a combination of late Gothic construction alongside earlier Mudejar elements and later Plateresque and Renaissance additions.

Why It Matters: History and Context

When Ferdinand III of Castile conquered Seville in 1248, he transformed the greatest city of Islamic al-Andalus into the crown jewel of Christian Spain. The Reconquista was reaching its zenith, and Ferdinand — later canonized as San Fernando — converted the city’s magnificent Almohad mosque into a cathedral. For over a century, this converted mosque functioned as the seat of Seville’s bishopric, a powerful symbol of Christian triumph over Islamic rule.

But by 1401, the cathedral chapter had grander ambitions. According to legend, they declared their intention to build something so massive and magnificent “that those who see it completed will think we were mad.” The old mosque was demolished — save for the mosque’s beloved bell tower (la Giralda; figure 13 and “In Detail” below) and northern courtyard (the “Court of Oranges”; figures 3 & 14-15) — and construction began on what would become the largest Gothic cathedral in the world.

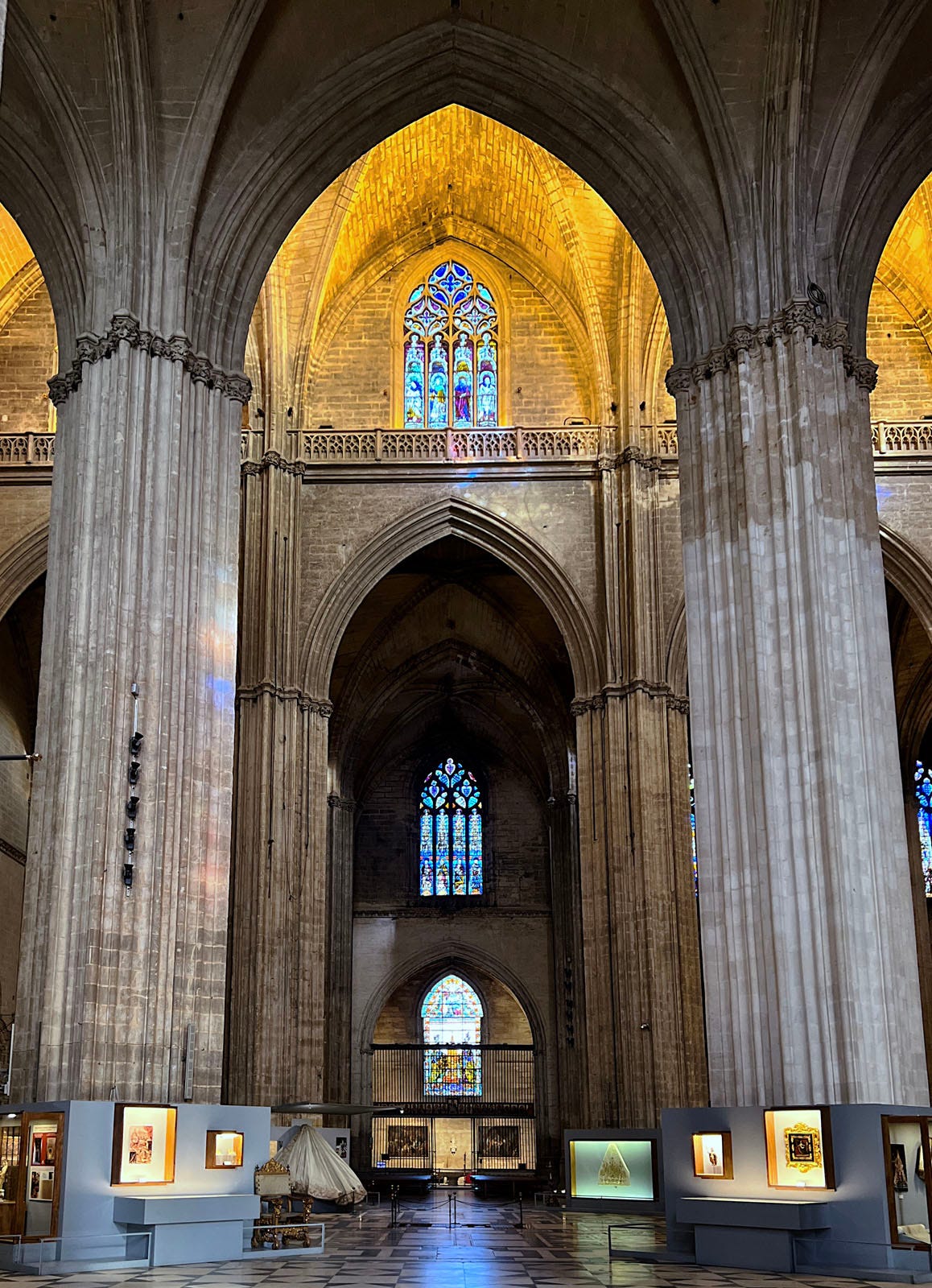

Work commenced in 1402 under Master Alonso Martinez, who established the cathedral’s basic plan: a massive five-aisled hall church with an unusually wide nave and exceptionally tall vaults. The project was deliberately ambitious — the chapter wanted their cathedral to rival any in Europe while asserting Seville’s growing importance as a commercial center.

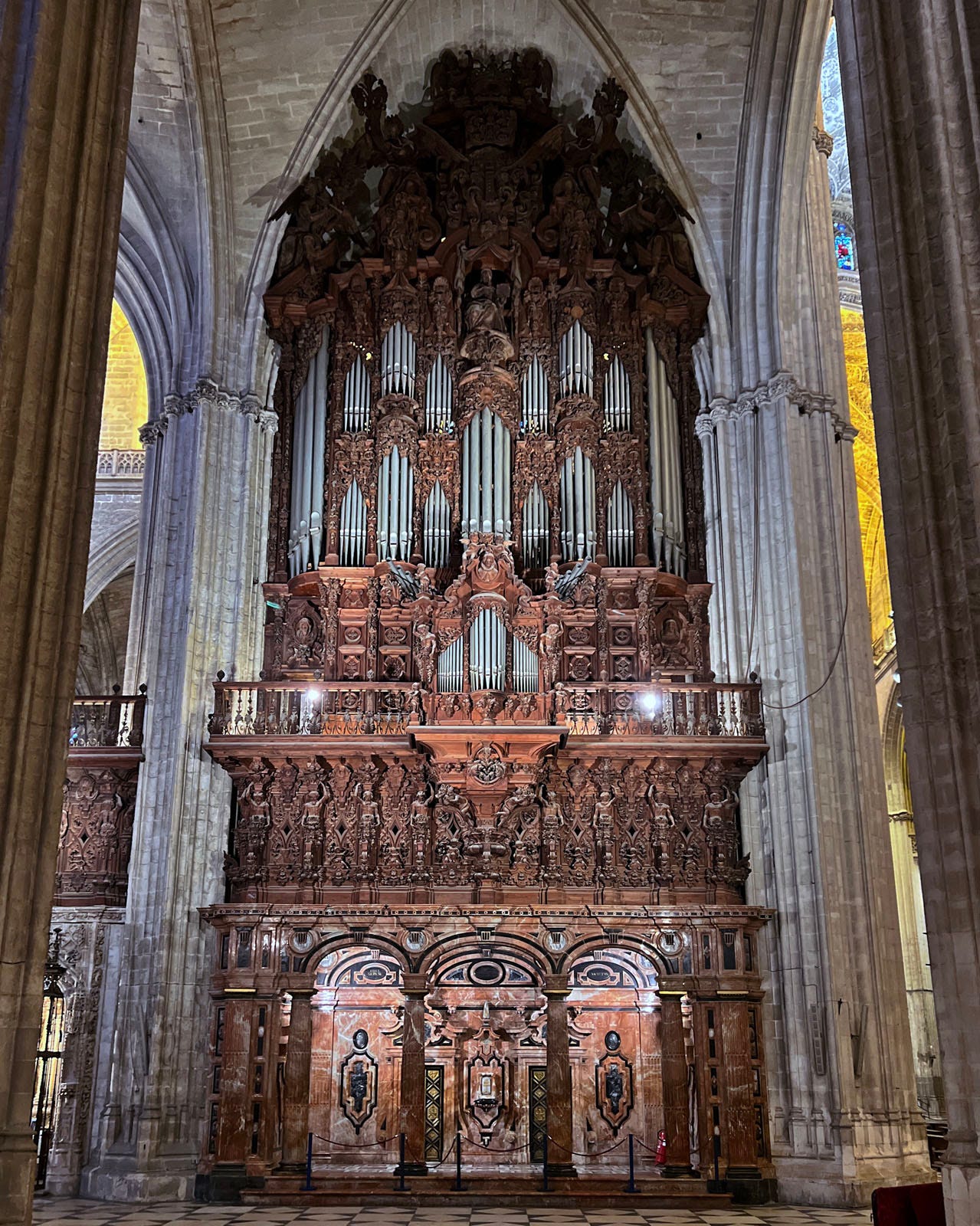

Construction proceeded rapidly through the 15th century, driven by Seville’s increasing prosperity from Atlantic trade. The main structure was largely complete by 1506, though work continued on details and furnishings for decades. The builders employed a late Gothic style, but one heavily influenced by the decorative traditions that had flourished in Islamic Spain. Mudejar craftsmen, working alongside Gothic masters, created a uniquely Spanish synthesis of Christian and Islamic artistic traditions.

The cathedral’s enormous scale reflected both religious devotion and civic pride. At 135m (440ft) long and 100m (330ft) wide, and with vaults soaring almost 40m (130ft) high, it dwarfed even the great French cathedrals.

As construction neared completion in the early 16th century, Seville’s role as the exclusive port for New World trade transformed both the city and its cathedral. Gold and silver from the Americas flowed through Seville’s docks, making it perhaps the most important city in Europe for a time. The cathedral became both a symbol and beneficiary of this wealth, its treasuries filling with precious objects while its chapels hosted the funerals and celebrations of Spain’s imperial elite.

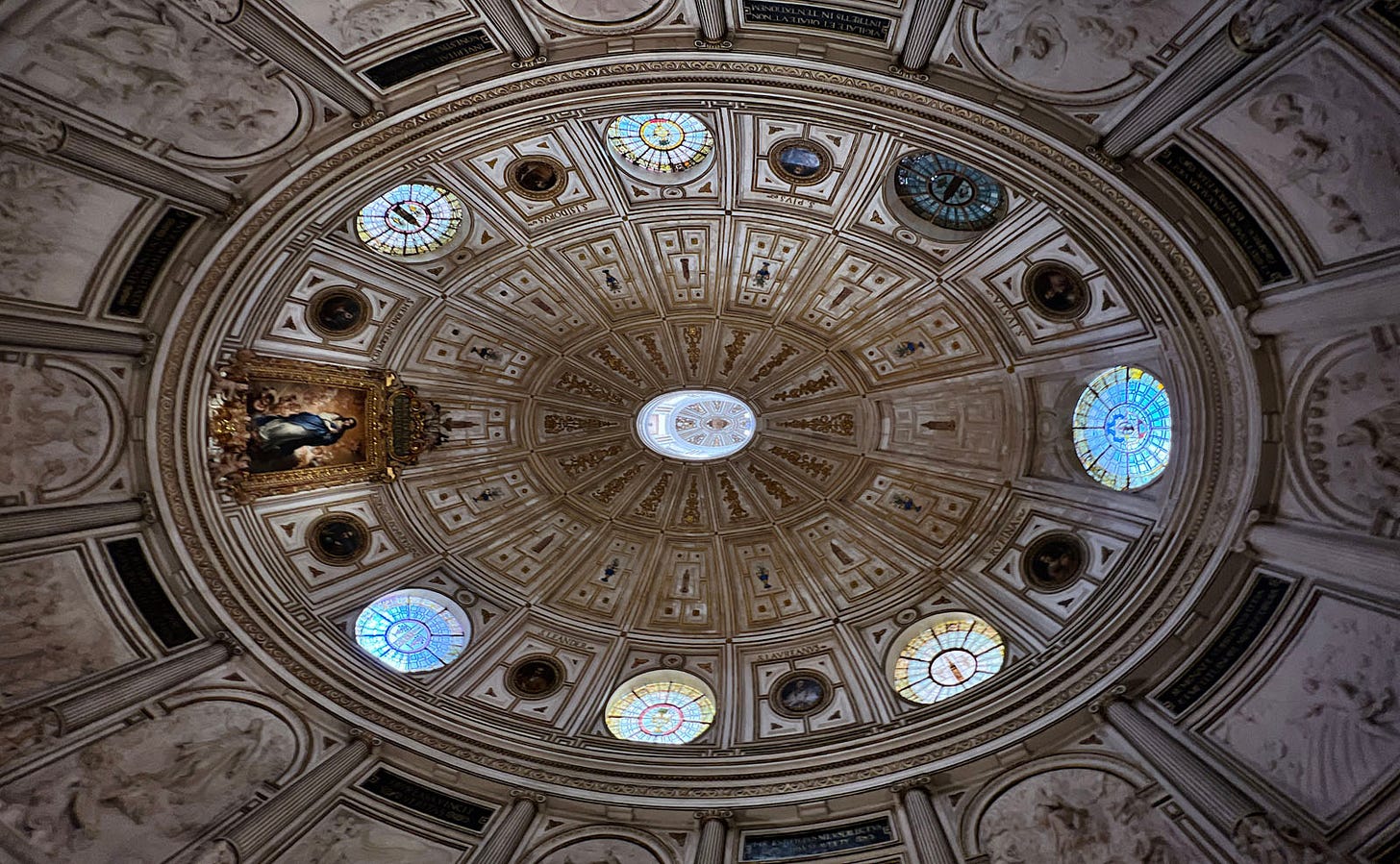

This imperial period brought new construction campaigns that reflected changing architectural tastes. The chapter house (figure 4) is an elegant Renaissance number and the sacristy (see “In Detail” below) exemplifies the ornate Plateresque style — a Spanish mode that could lean either (or both) Gothic or Renaissance, combining architectural forms with the intricate ornamentation associated with Spanish silverwork. The Baroque period brought new altarpieces and decorative schemes, while the 18th and 19th centuries saw various restoration campaigns and monument installations.

Each era left its mark, creating the complex palimpsest of styles visible today. And while the installation of so many monuments inside the main church — along with the many later accretions added to the sides — threatens to overwhelm, the underlying Gothic structure shines through, both inside and out.

Photo Tour

In addition to having several additions on the south side and a walled in courtyard to to the north, Seville’s cathedral is fairly hemmed in on most sides by other buildings. So getting a sense of the whole requires a walk around the entire place and a lot of imagination. Photos 7-14 below go counterclockwise from the west to the north, looking at important or photogenic elements.

Unusually for a cathedral, there are several portals on the east end, including one whose c1520 tympanum has made one of the Magi out to look like Christopher Columbus (so it seems to me) in an Adoration scene (figure 12).

The majority of the bell tower (figure 13 and “In Detail” below) was constructed in the late 12th century as a minaret for the mosque. In the mid-16th century a Renaissance style belfry was added along with a statue called “El Giraldillo” — installed in the year 1568.

Likewise, the entrance gate to the Court of Oranges (figure 14) includes original elements of the mosque, such as the tell-tale horseshoe arch.

Given all its interior installations, the cathedral is as hard to get a full handle on inside as out, though figure 1 — taken from the west end of the nave looking east — is a good view, even showing hints of the five-aisle design’s outermost side aisles at the edges.

A tomb monument to Ferdinand III stands in the center of the nave at its west end, looking up towards the crossing tower and apse (figures 17-18).

Figures 19-23 show views from the south side of the cathedral.

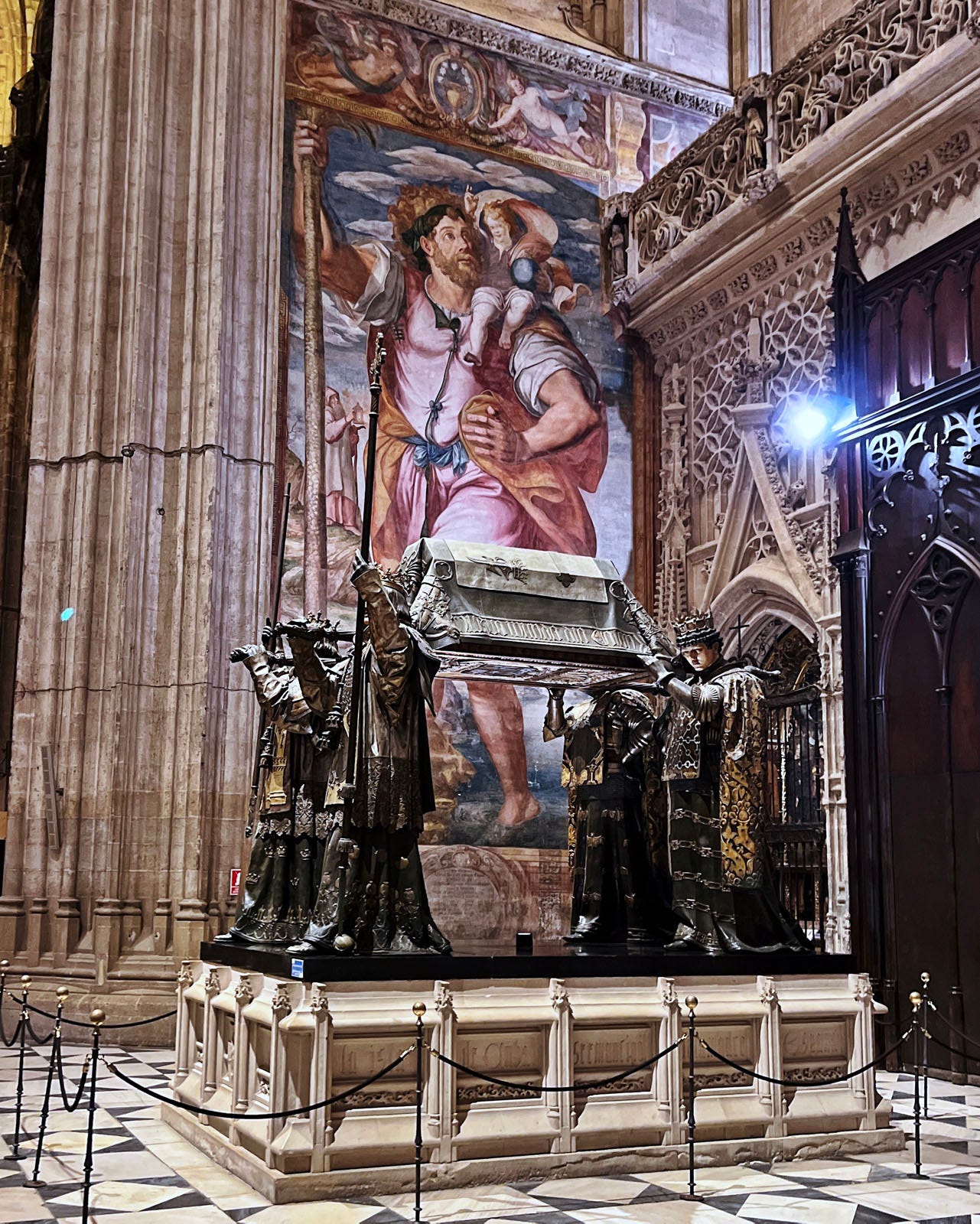

The tomb of Christopher Columbus (figure 23 and “In Detail”) is in the south transept, next to — appropriately enough — a massive fresco of St Christopher (patron saint of travelers in addition to charing Columbus’ name). The tomb was installed in 1899, after having first been in Havana Cuba, and whether the remains are indeed Columbus’ is contested.

Figures 26-67 show the north transept.

Figures 28-30 show various side chapels and side buildings (as does one of the Notes inmbedded in “In Detail” below). These contain an impressive collection of Spanish art from the 13th to 19th centuries.

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

In Detail

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 12 January 2023

Seville has a lot to offer and is worth a visit of at least several days, if not a full week.

The Real Alcazar is as impressive as the cathedral, and the Plaza de Espana — built in spectacular Neo-Mudejar style in 1929 — is an amazing place to take in the golden hour and sunset. Plus there are a dozen or more art museums and additional historical buildings whose interiors you can tour spread around the old city center.

Seville Cathedral is at the heart of the city, however, and a visit to it will remain with you long after you leave. It stands as more than just the world’s largest Gothic church: it embodies the ambitions of a city that briefly stood at the center of global empire, where New World wealth funded Old World artistic traditions, and where Christian and Islamic cultures combined to create something entirely new. The result is unmistakably Spanish — grandly scaled, richly decorated, and utterly confident of its own magnificence.

Informative, well-considered commentary as usual. Another winner! Thank you.

Incredible! I’m seeing some Moorish influence.?