(13 min read) A visual introduction to one of the most pradigmatic art form of medieval Europe.

Tapestries were the most monumental and multi-sensory form of two-dimensional art in the Gothic world, developing into their most elaborate and culturally dominant form during the High and Late Middle Ages — as paradigmatic of medieval aesthetics as illuminated manuscripts and Gothic cathedrals.

This essay offers a brief introduction to the medium, designed to help you appreciate the subtleties of form, theme, and style when you encounter tapestries in museums. It is illustrated with over thirty examples from my own collection of photos taken across museums and historical sites in Europe.

And if those images don’t fully sate your appetite for woven wonders, there are ten Substack Notes embedded at the end of this essay — each showcasing a single tapestry in detail, with multiple photos and extended commentary.

Introduction: What Is a Tapestry?

A tapestry is a textile in which the image is woven directly into the fabric itself, rather than embroidered or painted on top. Unlike embroidery — such as the famous but mis-named Bayeux Tapestry (figure 2), which narrates the Norman conquest in stitched wool — true tapestries are produced on looms, with warp threads held taut and weft threads manipulated by hand to form pictorial designs. The distinction is more than technical: woven tapestries were more durable, more monumental, and more complex to produce.

While fragmentary examples exist from earlier periods (eg, figure 3), showing that figural tapestry weaving predates the Gothic period, it was in medieval Europe that the form reached its full narrative and artistic maturity.

Sidebar: Only the cultures of pre-Columbian Peru (see Note below) approach medieval Europe in using large-scale woven textiles as a narrative medium — a remarkable parallel development across time and space.

Though the sections below organize examples by function, style, and theme, many of these tapestries blur those lines. I may show each as an example of a single region or function, but most of the works below could be provided as examples of both a specific region and theme, and/or of multiple themes, motifs, and functions.

I may not mention them all, but you’ll find overlaps throughout the categories and examples.

The Tapestry as Object: Function and Context

Tapestries were not just art — they were status symbols, storytelling media, and tools of institutional identity. Hung in castles, churches, and guildhalls, they served to insulate stone walls, shape acoustics, and stage ideology. Royal patrons commissioned cycles to assert power and cultivate prestige: for example the vast Apocalypse Tapestries (figure 1), created for Louis I of Anjou, dramatized divine order and dynastic legitimacy amid a chaotic age.

Royal and noble households used them to display lineage and heraldry, as in the tapestry bearing Edward IV’s coat of arms and given to a local nobleman (figure 4) , or as backdrops for thrones, like the woven panel behind Charles VII (figure 5).

Churches and cathedral chapters, commissioned them, or were given them as donations, to glorify saints and sacraments (figure 6).

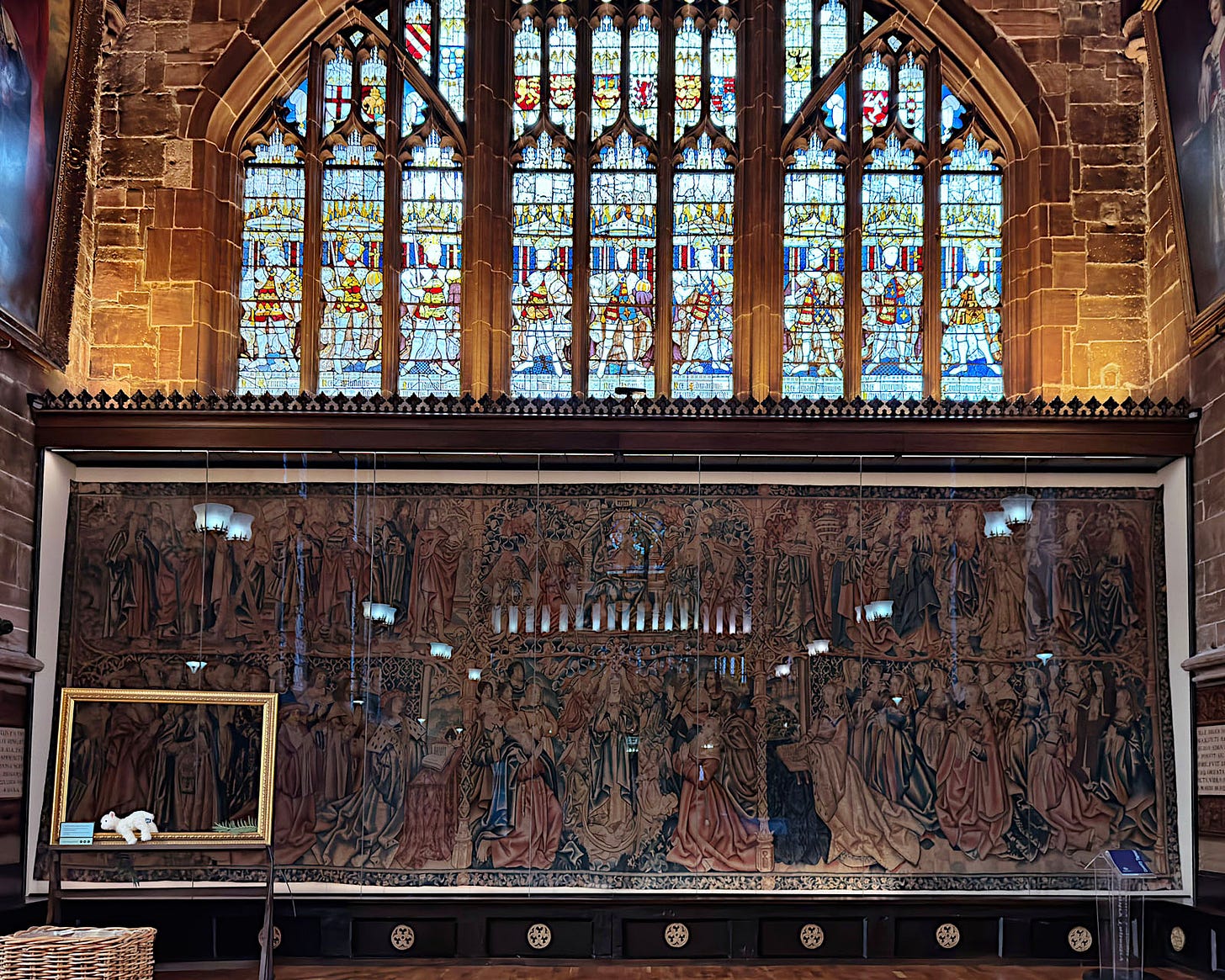

The grand Coventry Tapestry (figures 7–8), displayed in the guildhall of a prosperous English town, exemplifies how secular institutions also harnessed the medium’s visual power. These works were portable, reusable, and often narratively rich — designed to impress, instruct, and perform presence in spaces where stone and paint could not.

Technique & Production: The Loom & the Workshop

Tapestries were woven on vertical or horizontal looms, with the image built thread by thread as colored weft yarns passed through a grid of fixed warp threads (figure 9). Since the image was often created in reverse, detailed cartoons (full-scale drawings) were used as guides behind or beneath the threads. Monumental pieces exceeded the limits of a single loom, so panels were woven separately and stitched together later.

By the late Middle Ages, professional workshops had emerged in cities like Paris, Arras, Strasbourg, Basel, and Brussels. By the 15th century, Brussels had become the undisputed capital of tapestry production.

The word “workshop” can be misleading: in cities like Arras and Brussels, it rarely meant a single room. A master weaver or merchant managed a team of artisans working across multiple buildings — each handling different stages, from dyeing and spinning to weaving individual panels. These ateliers functioned more like decentralized manufactories, with shared cartoons and tight guild regulation. By the 15th century, Brussels had become the tapestry capital of Europe, renowned for its scale, coordination, and artistic excellence.

Styles: Regions & Motifs

While full scenes dominate many tapestries, specific motifs became widespread, especially in decorative or allegorical works.

The mille-fleurs style — a scattered field of tiny plants and animals on a single-color ground — adds both whimsy and symbolism (figures 10–11). Heraldic devices are ubiquitous, proclaiming lineage, allegiance, or commission (figure 11). Scrolls or banderoles with text often accompany figures, functioning like speech bubbles or labels (figure 12).

Flanders

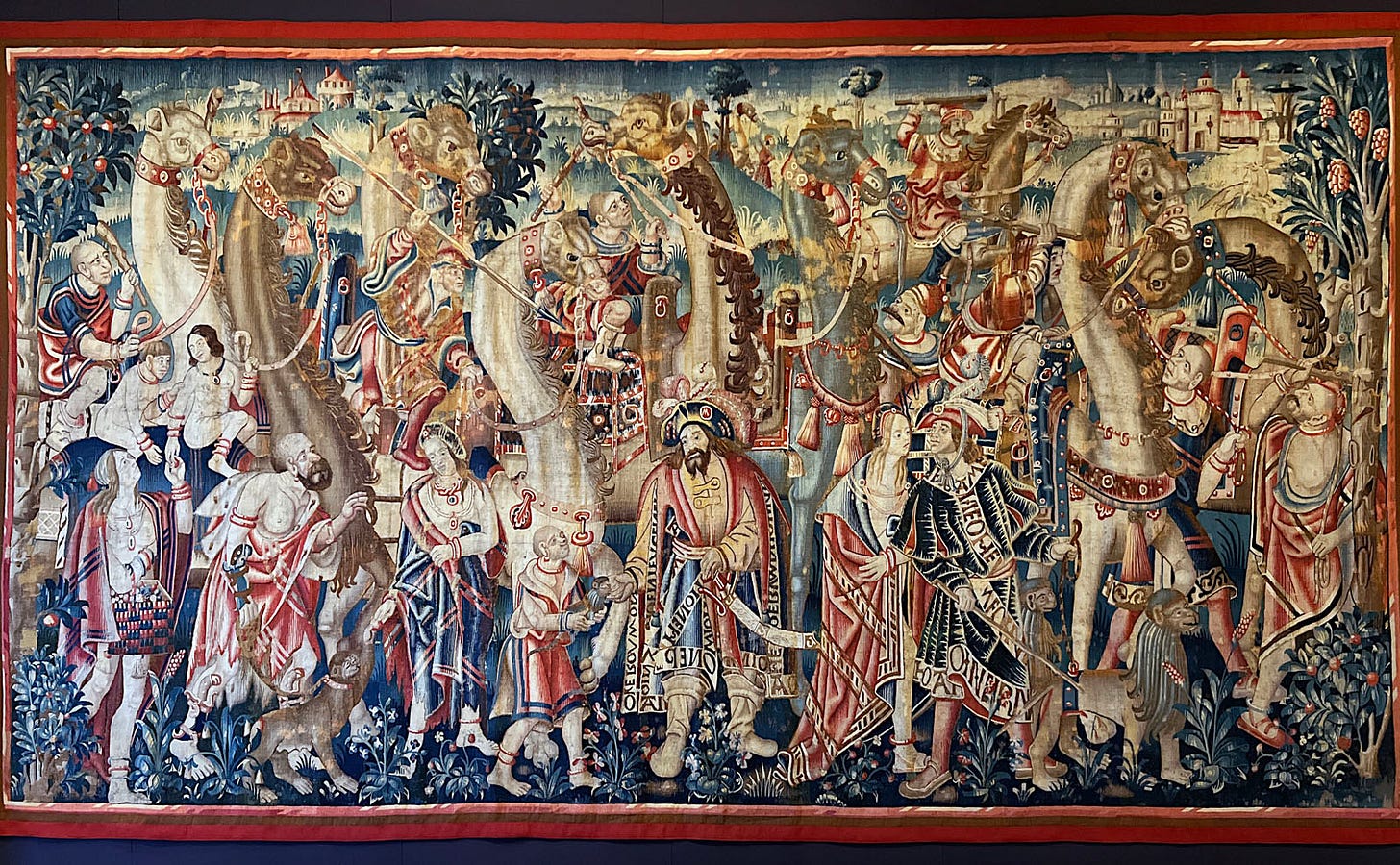

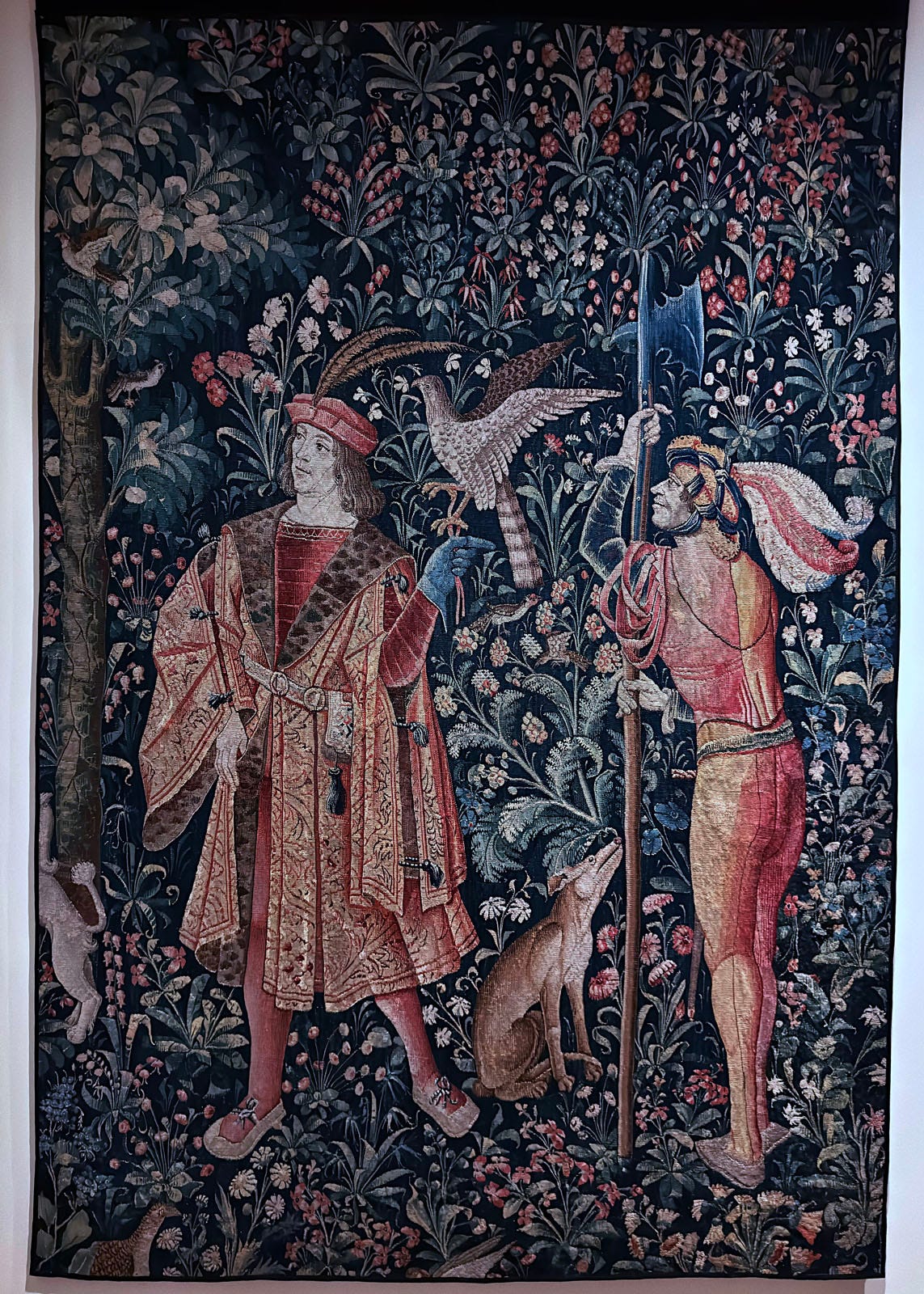

Flemish workshops — especially in Brussels and Tournai — produced the most ambitious, technically accomplished tapestries of the late Middle Ages. Their works are often larger, more “realistic,” and classically themed than their French or German counterparts.

Mythological cycles like Hercules Founding the Olympic Games (figure 13) or sprawling aristocratic hunting scenes (figure 14) showcase detailed landscapes, expressive anatomy, and a clear debt to contemporary panel painting. Flanders was the only region where tapestry reached something like a proto-Renaissance pictorial realism, while maintaining its woven texture and narrative power.

France

French tapestries, particularly from Paris and the Loire region, often blend decorative charm with narrative sophistication. The mille-fleurs style, though pan-European, became a hallmark of Parisian ateliers.

Scenes of aristocratic life — like the Departure for the Hunt or the rustic but symbolic Wine Harvest (figure 16) — strike a balance between fantasy and realism. French tapestries tend toward elegance over drama, with softer color palettes and stylized figures. Many were intended for private spaces rather than public display, imbuing them with a tone that’s more courtly and contemplative than propagandistic.

Alsace/German/Swiss

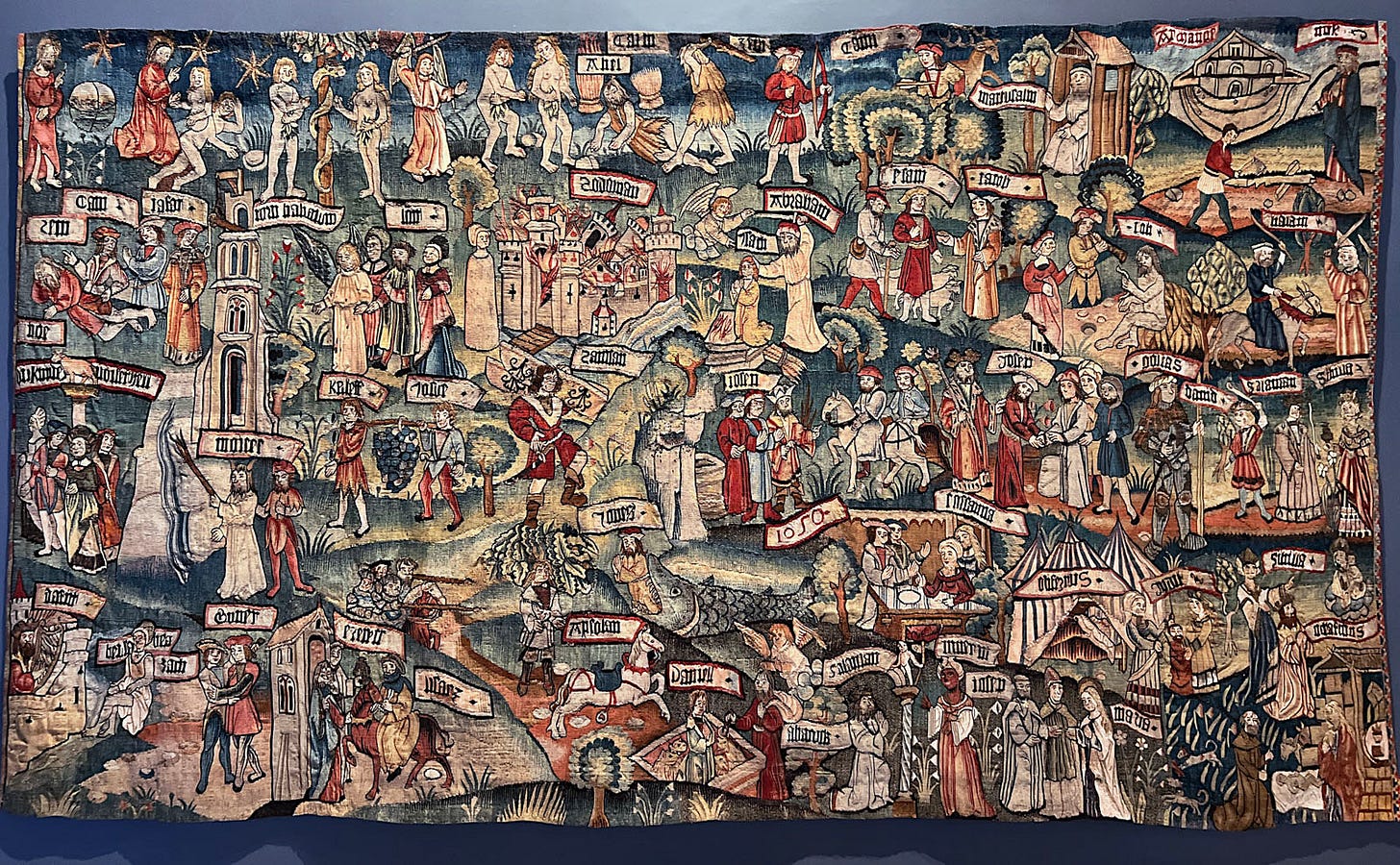

Tapestries from the southern German-speaking world — especially Alsace, the Rhineland, and Swiss cities like Basel — often feel more intimate and idiosyncratic.

Their figures tend toward a blocky, stylized aesthetic (figures 17–18), sometimes bordering on the cartoonish. These works are typically smaller in scale and more regionally inflected in tone, mixing in more folkloric elements.

Themes: Religious, Courtly, and Allegorical

Religious imagery dominated the earliest narrative tapestries and remained a central theme throughout the medieval period. From Passion scenes woven for cathedral treasuries (figure 19) to cycles honoring local saints like St. Attalus (fig. 20), these works served both didactic and devotional purposes. The Adoration of the Magi appears frequently (figures 21, 23), likely due to its associations with gift-giving, kingship, and cosmic recognition. Marian themes, too, were especially popular — the Our Lady of Sorrows panel (figure 22) offers both intimate piety and courtly elegance. These religious tapestries often echoed liturgical rhythms and mirrored the theological calendar.

Tapestries were ideally suited to the self-image of the nobility: expansive, refined, and full of coded meaning. Scenes of dining (figure 24), feudal life (figure 25), courtship, or heraldic romance (figure 26–27) were woven to reinforce class identity and ideals of comportment.

The “Offering of the Heart” turns private emotion into ritual gesture, while the “Love Garden” imagines flirtation within a decorative enclosure of tents, flowers, and symmetry. These were not just depictions of life, but visual performances of aristocratic values — often idealized, sometimes gently satirical, always aspirational.

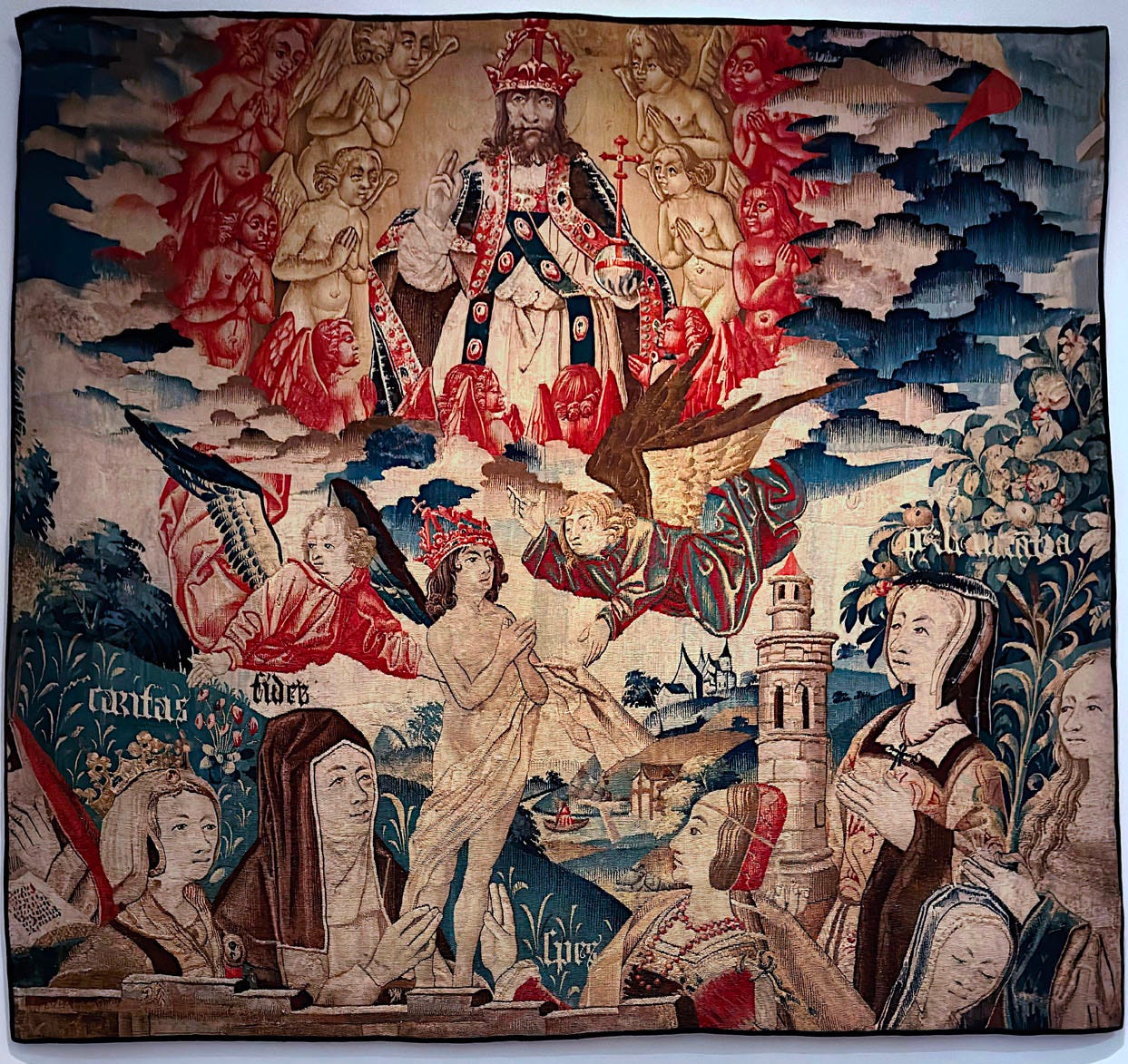

Strict personification-based allegory — with figures like Honor, Fortune, or Chastity — is less common in tapestry than in manuscript illumination or sculpture, but allegorical meaning pervades the medium. The Triumph and Death of Honor cycle (figure 28) is a rare direct example, blending chivalric mourning with moral symbolism.

More often, tapestries dramatized allegorical themes through action and tone: the “Wild People on a Stag Hunt” (figure 29) may look folkloric, but it likely comments on the tension between nature and culture, impulse and restraint. In medieval visual language, almost any hunt, feast, or battlefield could also be read as a metaphor.

Transitions & Traditions: Early Renaissance, Revival, Modern

As oil painting on canvas became more portable, vivid, and spatially convincing, it gradually eclipsed tapestry as Europe’s dominant visual medium. Yet tapestry never disappeared. Early modern workshops adapted by shifting to Renaissance themes — the Age of Exploration (figure 30), designs based on painters like Raphael (figure 31), and more doctrinal works like The Apostles’ Creed (figure 32), reflecting the growing emphasis on confessional clarity in the Reformation era.

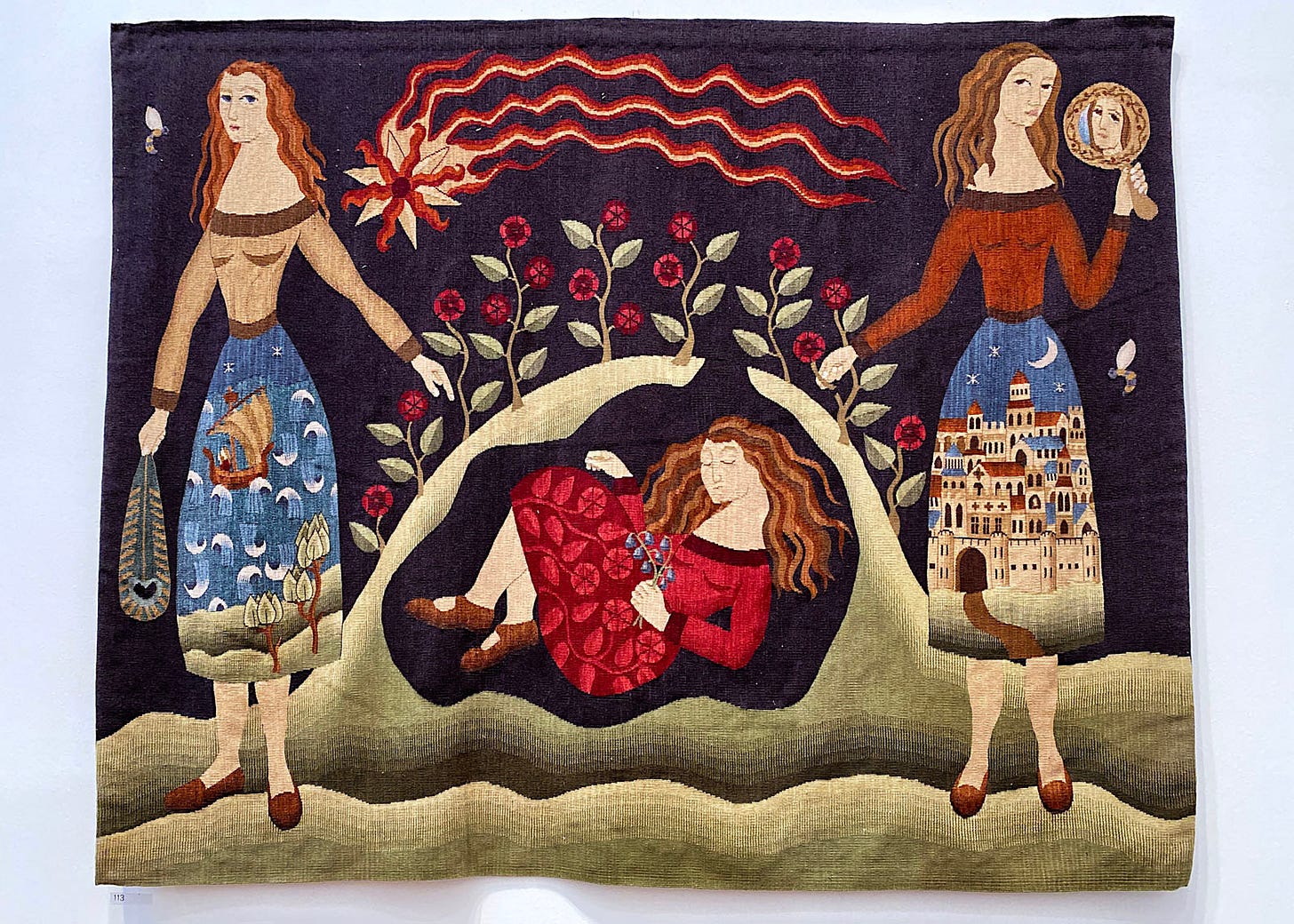

The 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement revived medieval aesthetics, as in William Morris’s Woodpecker Tapestry (figure 33), while contemporary artists like Chrissie Freeth (figire 34) continue to use the medium’s rich textures to explore modern ideas with clear inspiration from medieval motifs and themes.

Though no longer central to elite decoration, tapestry remains one of the most layered and materially rich art forms ever devised. And there’s something otherworldly about them still. More than sculpture or painting, a medieval tapestry can feel like a window into a different reality — one where saints and wildmen, angels and allegories, all move through a woven world of wonder.

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Postscript

You may have noticed that some of the most famous tapestry cycles — The Hunt of the Unicorn, the Lady and the Unicorn, and the Apocalypse Tapestries — are only briefly mentioned here or not included at all. That’s intentional. I’ve photographed and documented those in detail and will be publishing a dedicated essay on the two unicorn tapestry cycles next month, and on the Apocalypse Tapestries in due time.

In Detail

Here are ten Substack Notes describing in detail a number of the tapestries above that I happen to particularly like. They are presented in chronological order.

This might be one of the best posts I have ever seen. The attention to detail, the image clarity, and the essay itself..it’s a masterclass in putting together an engaging piece.

Fascinating ,- I'll look more closely. But aren't those early Latin American ones extraordinary!