(7 min read) Freiberg Minster — number 35 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is remarkable for its preservation, range of styles, openwork spire, and vast collection of sculpture.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Freiberg Minster

Official Name: Muenster Unserer Lieben Frau (The Cathedral/Minster of Our Lady)

Location: Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: c1230-c1530

Why It’s Great

One of the earliest major Gothic projects in southern Germany, Freiburg is remarkable for its exceptional level of preservation. Its openwork stone spire was the first of its kind, setting a precedent that would influence many churches over the next several centuries. The building also presents a complete progression of styles, from late Romanesque to late Gothic, and contains a wealth of outstanding medieval statuary and stained glass.

Why It Matters: History and Context

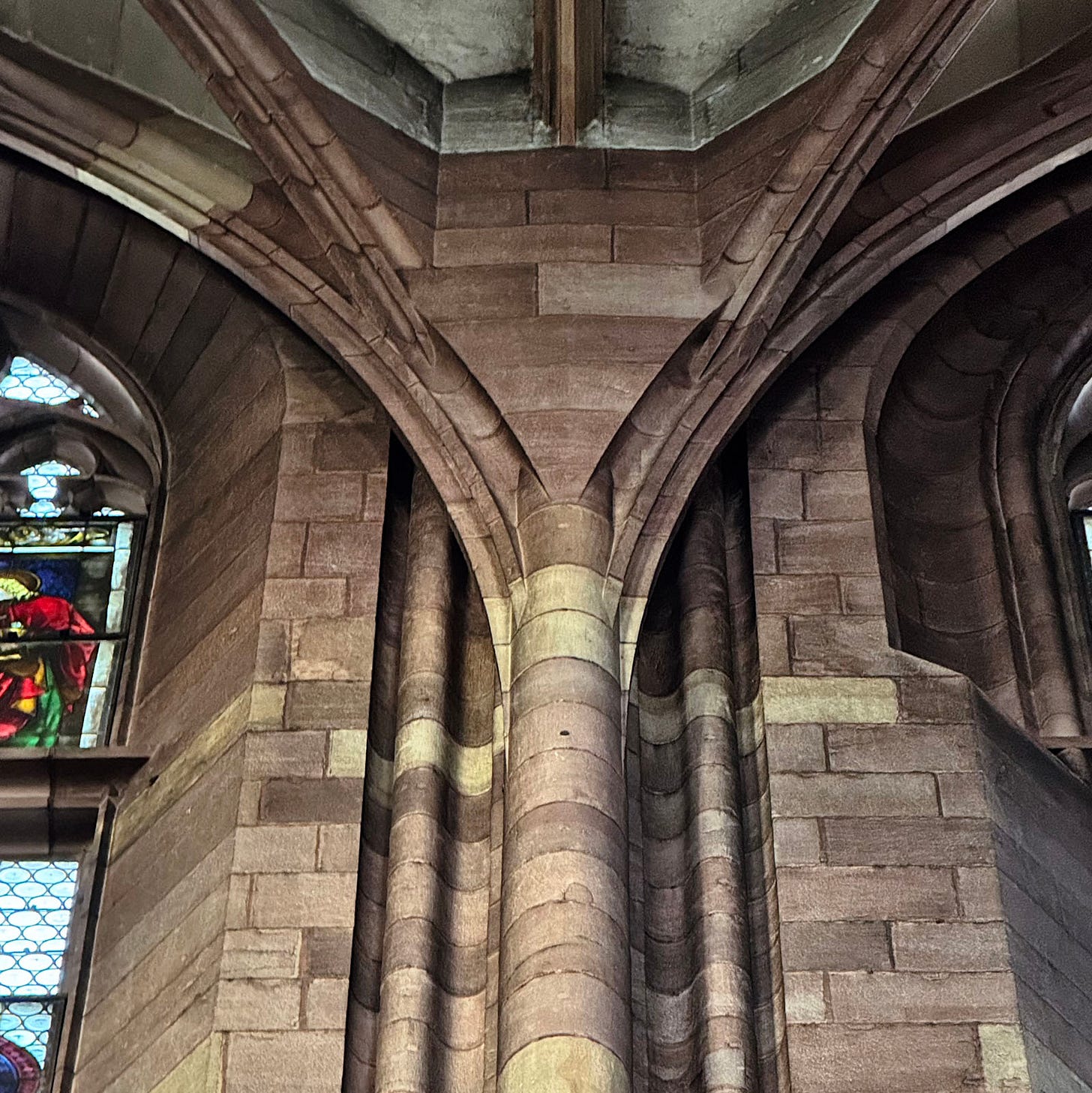

Construction of the Freiburg Minster began around 1200 as a late Romanesque church commissioned by Duke Berthold V of Zähringen. In the 1230s, the project underwent a dramatic shift, abandoning its Romanesque plan in favor of the emerging Gothic style spreading from northern France and the Upper Rhine. Much of the Romanesque nave was dismantled, and new work began using pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses—resulting in a visible “seam” where earlier and later phases meet.

The eastern nave bays were completed by the mid-13th century in a transitional Gothic style. Over the next several decades, construction moved westward. The western nave bays, completed between roughly 1260 and 1300, show increasingly sophisticated Gothic detailing. Each bay reflects a subtle stylistic evolution, visible in the vaulting, tracery, and sculpture.

The cathedral’s iconic west tower was constructed in two main stages. The massive square lower section was raised between 1270 and 1290. Then, from the 1290s to around 1330–1340, builders added the octagonal belfry and the revolutionary 46-meter openwork spire—a stone lattice of intersecting ribs and tracery. It remains the first fully openwork spire in Gothic architecture and one of the most influential.

Work on the eastern choir progressed more slowly. Around 1354, Johannes von Gmünd (grandfather of Peter Parler, whom we will meet later in this series) began construction of a new high choir with radiating chapels. This phase stalled during the crises of the late 14th century, including plague and economic strain, and resumed only in 1471 under Hans Niesenberger of Graz.

The timber roof over the chancel was in place by 1481, and the vaulting completed by 1510. In 1513, after more than three centuries of intermittent building, the Freiburg Minster was formally consecrated. Final work on the chapel ring continued into the 1530s, with the last stones laid in 1536.

In the post-medieval centuries, the minster saw significant adaptation. Renaissance additions included a new chapel (1555), a richly carved stone rood screen (1579–1583), and sculptural epitaphs in the classical style. The 18th century brought Baroque interventions—whitewashed walls, gilded altars, and simplified glazing. After Freiburg was elevated to an episcopal seat in 1827, a Gothic Revival campaign stripped away most Baroque additions and reintroduced medievalizing elements, often informed more by 19th-century ideals than original design.

Freiburg Minster was nearly lost during the Allied air raid of November 27, 1944, which obliterated much of the city center. Miraculously, the minster escaped direct hits. Though the roof was torn off and windows blown in, the structural skeleton held firm. Rapid action by clergy and citizens saved the exposed vaults from collapse, and the building was largely restored by the 1950s.

Today, Freiburg Minster remains one of the few large Gothic cathedrals in Germany completed largely according to its medieval plan. Its remarkable architectural coherence—achieved over three centuries—makes it a vivid document of Gothic evolution, from early experiments to late flamboyance.

The church continues to serve as both a functioning cathedral and a living monument of medieval ingenuity. Ongoing conservation efforts focus on replacing decaying sandstone, restoring sculpture, and managing environmental damage without compromising historical integrity.

Photo Tour

The minster’s exterior is richly ornamented, especially on the south side (figures 7-9), where Gothic sculptural programs and structural innovations like flying buttresses converge. Some of the figures here are original, others replaced by hand-carved replicas in ongoing conservation efforts.

The west front of the Freiburg Minster (figures 3 & 10) is its most iconic face — dominated by a single, soaring spire of openwork tracery. Beneath it, the deep portal porch (figures 11-12) teems with narrative sculpture, a visual catechism of medieval theology and civic pride.

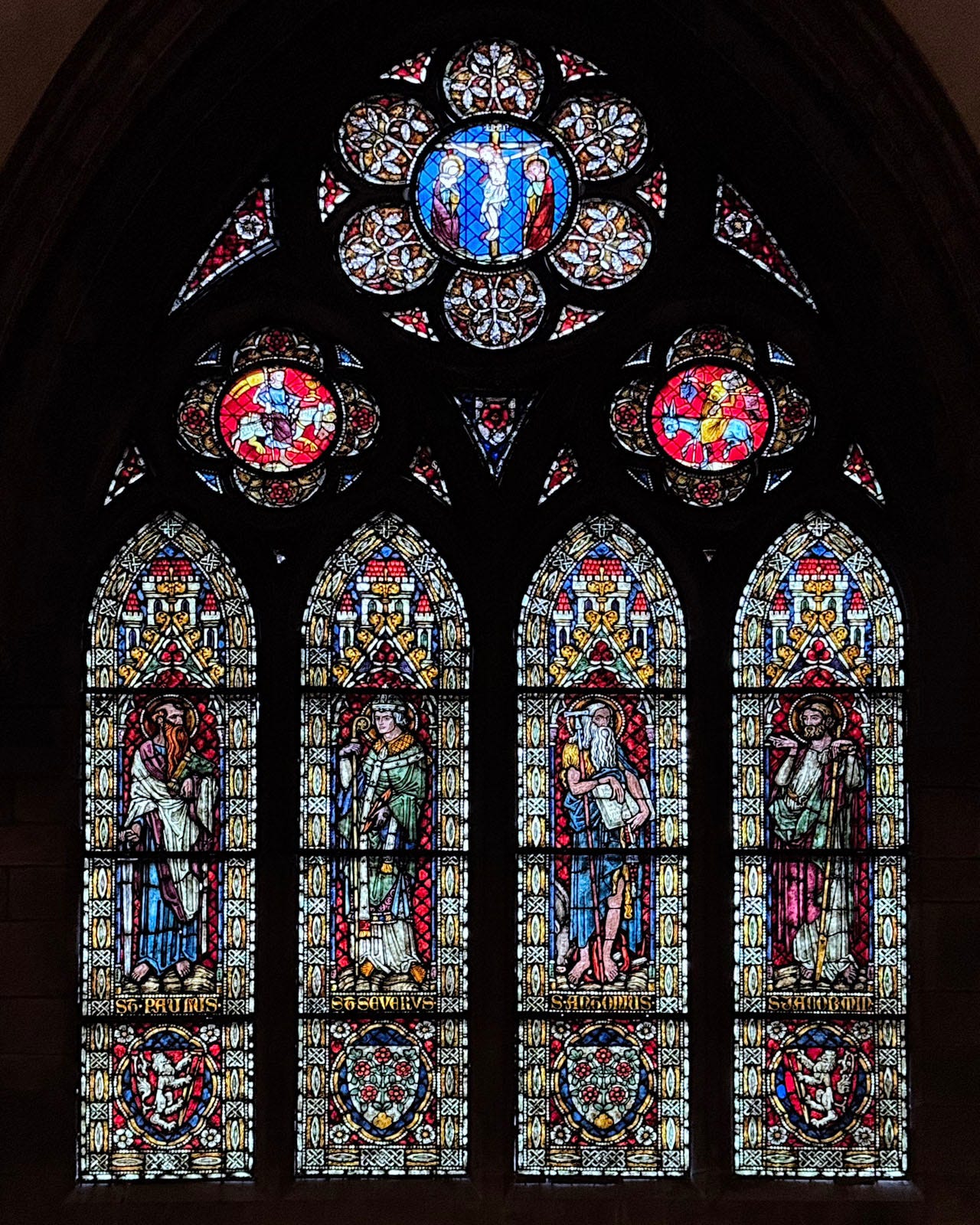

Inside, the nave (slides 1, 13, 15-17) reveals the layered chronology of construction — from the relatively restrained early Gothic bays in the east to the more elaborate tracery and vaulting of the west.

Art and architecture meet in the nave’s sculptural details: devotional figures at column capitals, a magnificent stone pulpit from the late Gothic period, and moments of iconography placed at the intersection of movement and liturgy.

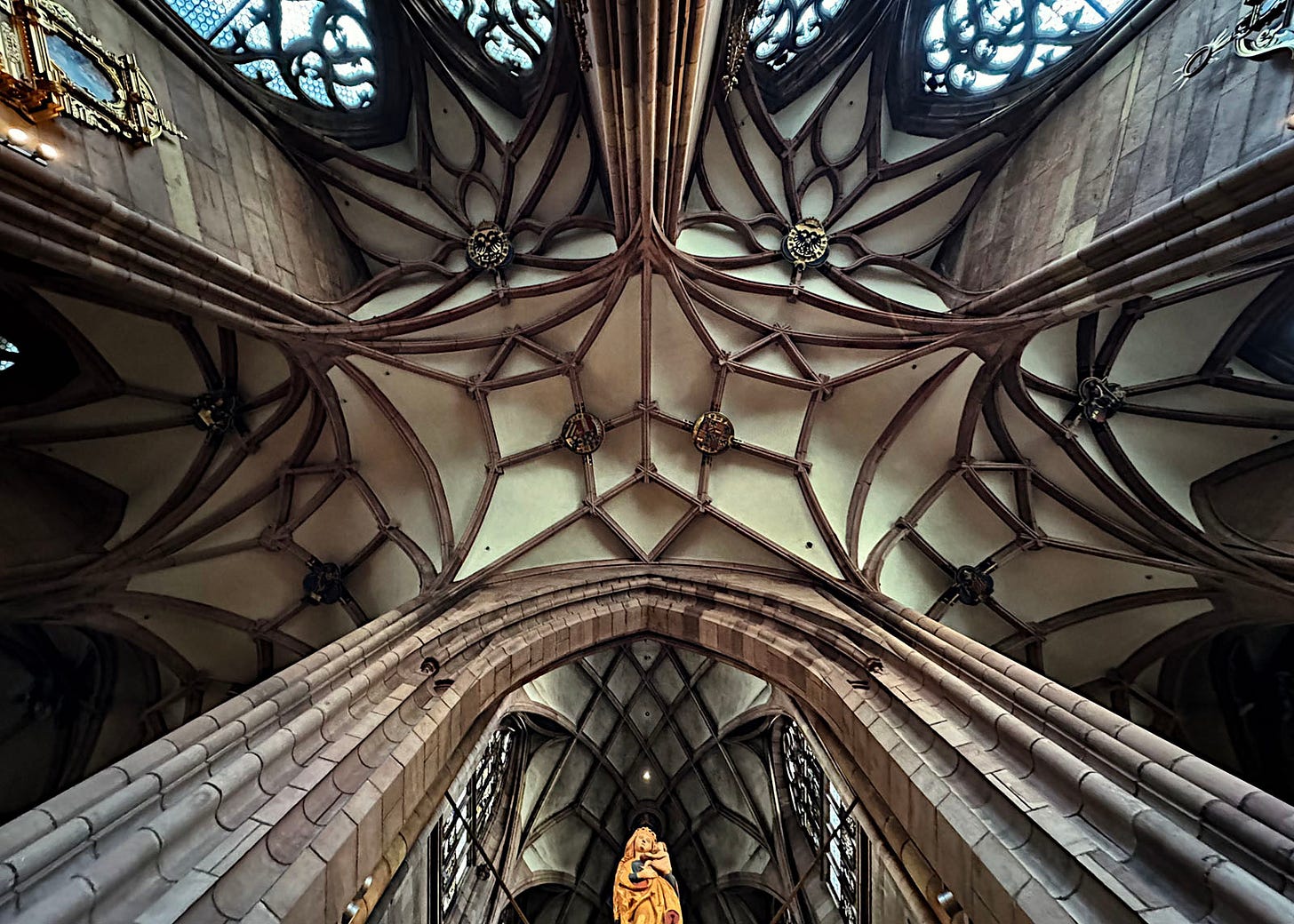

The chancel (figures 19-20), begun in the mid-14th century and completed in the early 16th, embodies the late Gothic style in its height, light, and intricate ceremonial focus.

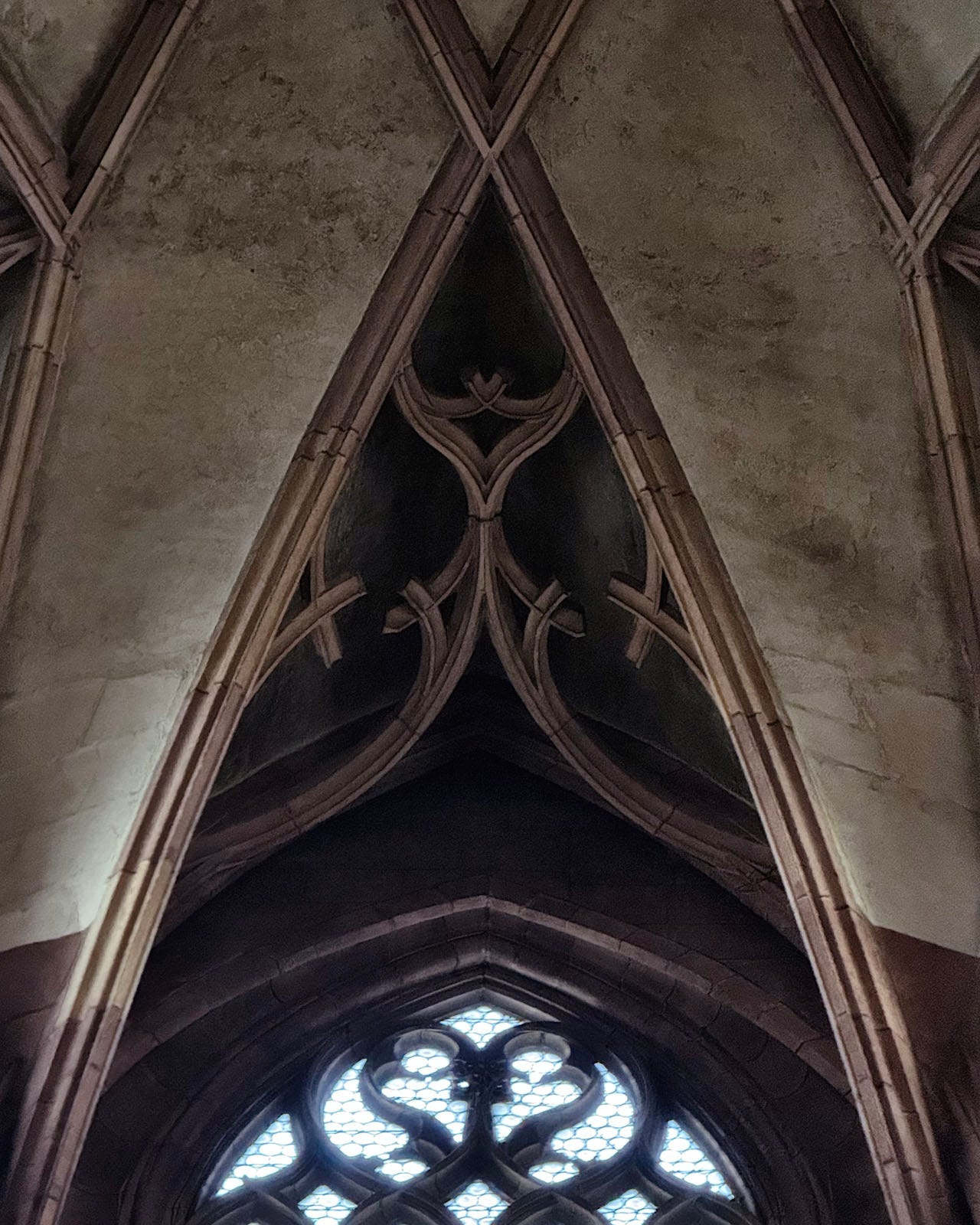

Vaulting in the chancel (figures 5, 21-22) achieves an organic grace, where ribs seem to grow from columns like vines. Here, structure becomes ornament — and vice versa.

Circling the apse is the ambulatory (figures 23-25), a ring of space behind the high altar that connects a series of chapels. It offers intimate glimpses of both architecture and devotion.

Side chapels (figures 26-27) vary in age and style, but many were completed in the 15th and 16th centuries and feature elaborate vault bosses, sculptural cycles, and late medieval stonework of remarkable delicacy.

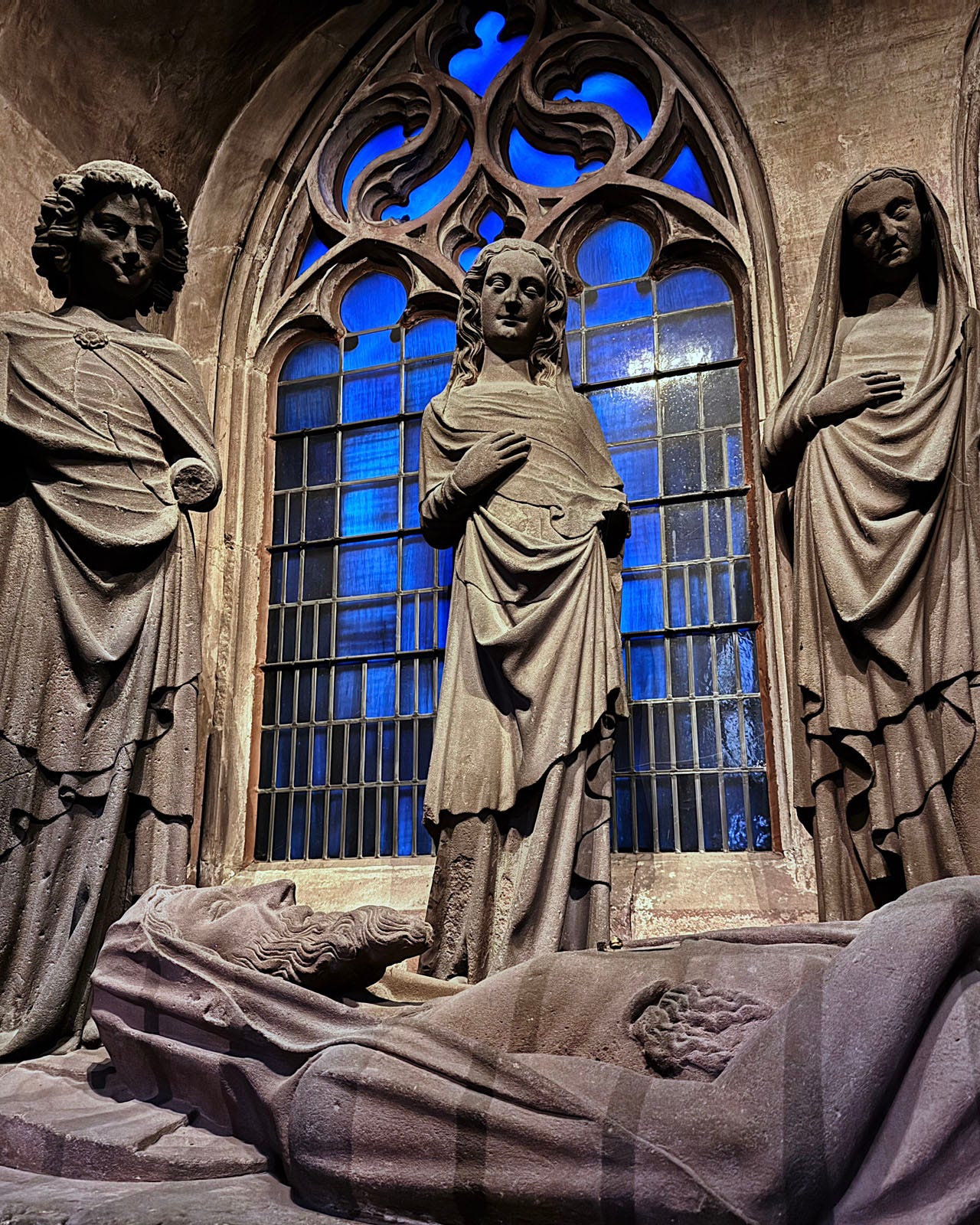

Among the chapels are expressive sculptural groups depicting scenes from the Christ’s Passion (figures 28-29).

Don’t Miss

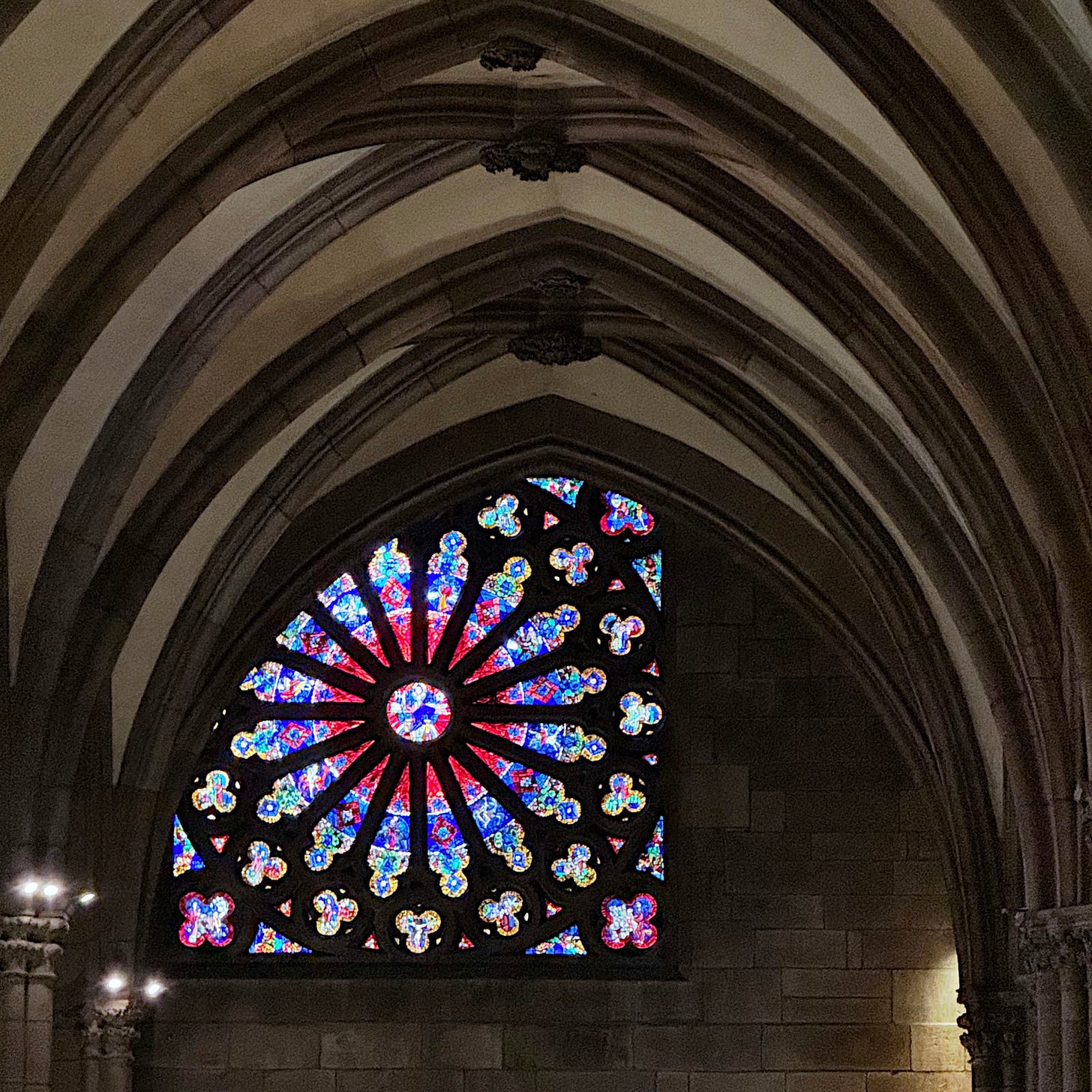

Many interesting seams and funky details exist here due to the the church’s growth over the centuries are are worth seeking out. The offset and partially obscured rose window at the end of the side aisle in figure 30 is a fun example. And a reminder that not everything can be — or even must be — “perfect.”

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 20 November 2024

Freiburg im Breisgau is more than a backdrop for the minster — it’s auniversity town at the edge of the Black Forest, known for its medieval street grid, market squares, and network of tiny canals called Bächle. Plan to spend at least a full afternoon here. After visiting the Minster, make time for the Augustinermuseum just a few minutes’ walk away — it holds many of the minster’s original sculptures, altarpieces, and stained glass panels, removed over the centuries for preservation.

Freiburg Minster bears the marks of history without being overwhelmed by them. The building’s layers — Romanesque to Gothic to Renaissance to Baroque to Gothic Revival — are not a patchwork but a record, each phase contributing to the whole. It is at once a monument, a memory palace, and a work in progress.

Incredible building, beautiful photographs. did you take them? Love the offset rose.