(9 min read) Siena Cathedral — number 32 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is a masterpiece of Italian Gothic architecture, where northern European structural principles blend harmoniously with distinct Italian decorative traditions.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Siena Cathedral

Official Name: Cattedrale metropolitana di Santa Maria Assunta (Metropolitan Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption)

Location: Siena, Italy

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1196-1348

Why It’s Great

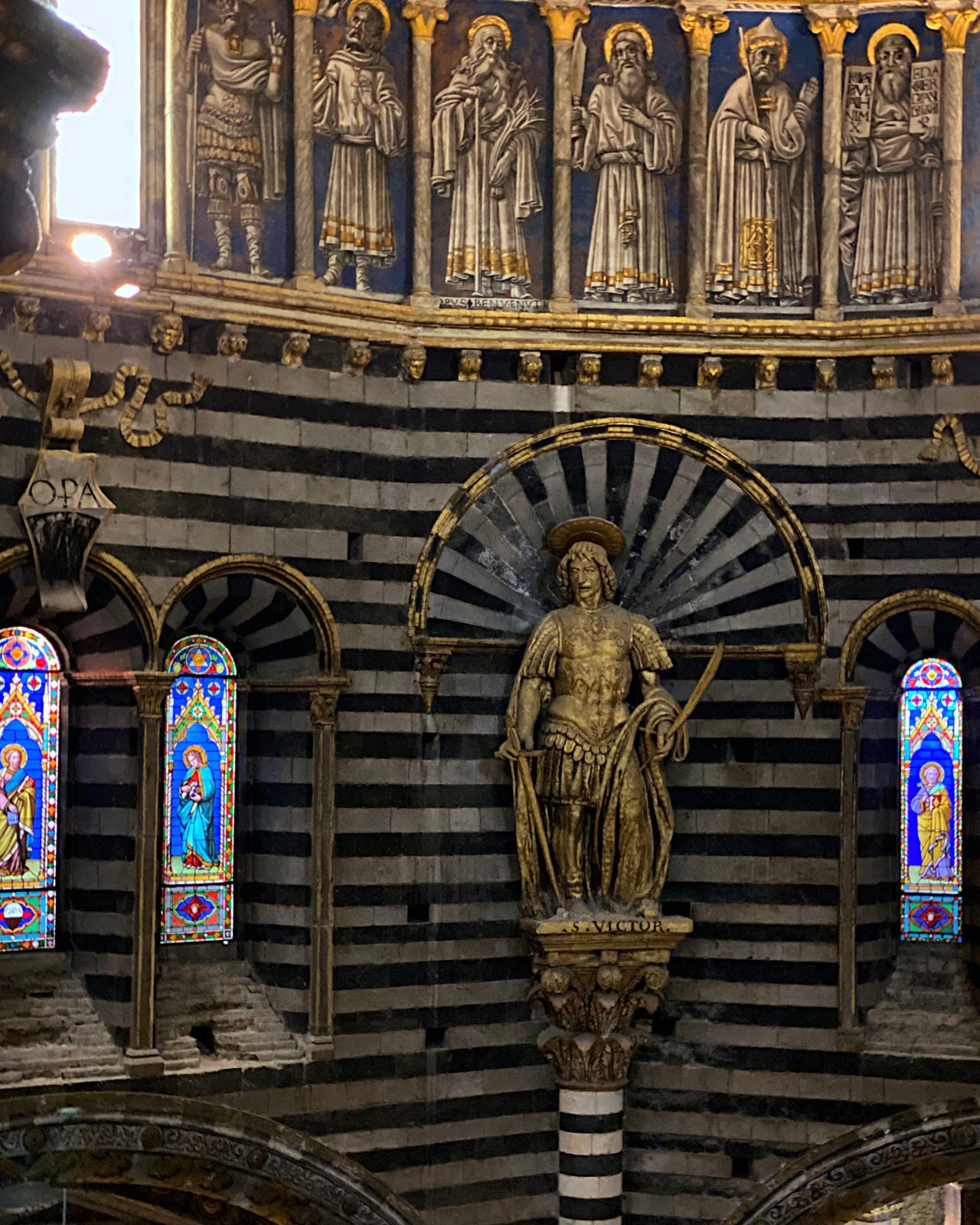

Siena Cathedral brilliantly synthesizes Gothic principles with Italian classical traditions, featuring the city’s signature black and white marble striping alongside exceptional sculptural work spanning the medieval to Renaissance periods. Its harmonious blend of northern European structural ambition with distinctly Italian decorative sensibilities — particularly evident in the baptistry’s remarkable ceiling paintings — makes it a perfect example of how Gothic architecture adapted to regional artistic traditions.

Why It Matters: History and Context

Siena Cathedral is one of Italy’s finest examples of Italian Gothic architecture, with several unique qualities. Its siting is one: it is oriented along on almost north-south axis, so its “west facade” actually faces SSW. In addition, unlike most city cathedrals, Siena’s is not positioned on the main square — the Piazza del Campo — but on its own elevated square, the Piazza del Duomo.

This placement atop one of Siena’s three hills emphasizes the cathedral’s spiritual and physical dominance over the medieval cityscape, while creating a distinct religious center separate from the civic heart of the community. Additionally, the cathedral’s most distinctive visual feature — its striking black and white marble striping — directly reflects Siena’s civic colors, symbolically linking the spiritual edifice to the city’s identity.

Construction began around 1226 (establishing dates of construction is unusually difficult with this cathedral) on the site of an earlier building, and the structure was largely complete by the end of the 13th century. Facade work, sculptures, and other detailing was still happening throughout the first half of the 14th C, however.

The cathedral’s construction history took a dramatic turn in 1339, when Siena, then at the height of its power and wealth, approved an extraordinarily ambitious expansion plan called the “Duomo Nuovo” (New Cathedral). This scheme would have transformed the existing cathedral into merely a transept of an enormous new structure extending southward, creating what would have been the largest church in Christendom at approximately 140 meters in length. The motivation behind this plan was largely competitive — Siena had learned of Florence’s plans to build “the largest cathedral in all of Tuscany” (see [link]this post) and was determined to outdo its rival.

Work on the Duomo Nuovo progressed for nearly a decade, with substantial portions of the new walls and some vaults constructed. However, two catastrophic events halted this ambitious project forever. First, in 1348, the Black Death devastated Siena, killing as much as half to two-thirds of the city’s population. Then, in 1357, structural defects were discovered in the new construction, rendering it unsafe to continue.

The abandoned expansion left behind the “Facciatone” — an impressive unfinished façade with partial walls that now houses the cathedral museum (Museo dell’Opera) and offers visitors spectacular views of the city from its summit. This architectural fragment stands as a poignant reminder of Siena’s once-grand ambitions and the city’s dramatic reversal of fortune following the plague.

Another unusual feature of Siena Cathedral is its baptistry arrangement. Unlike Florence or Pisa, which built separate baptistry buildings, Siena — having to deal with a steeply sloping site — incorporated its baptistry beneath the cathedral’s choir and eastern end. The baptistry serves as both a functional support for the eastern extension of the cathedral and a spiritually significant space in its own right.

Over the centuries, the cathedral complex continued to evolve with additions like the Piccolomini Library, commissioned in 1492. In the 17th century, Baroque elements were incorporated, including Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s lantern atop the dome and sculptures in the Chigi Chapel.

Today, the cathedral complex encompasses five interconnected structures: the cathedral itself, the library, the baptistry, the cathedral museum with the Facciatone viewing terrace, the crypt (rediscovered in 1999 during excavations). Together, they represent not just the architectural evolution of Gothic style in Italy, but also Siena’s complex history of ambition, competition, catastrophe, and remarkable artistic achievement.

Photo Tour

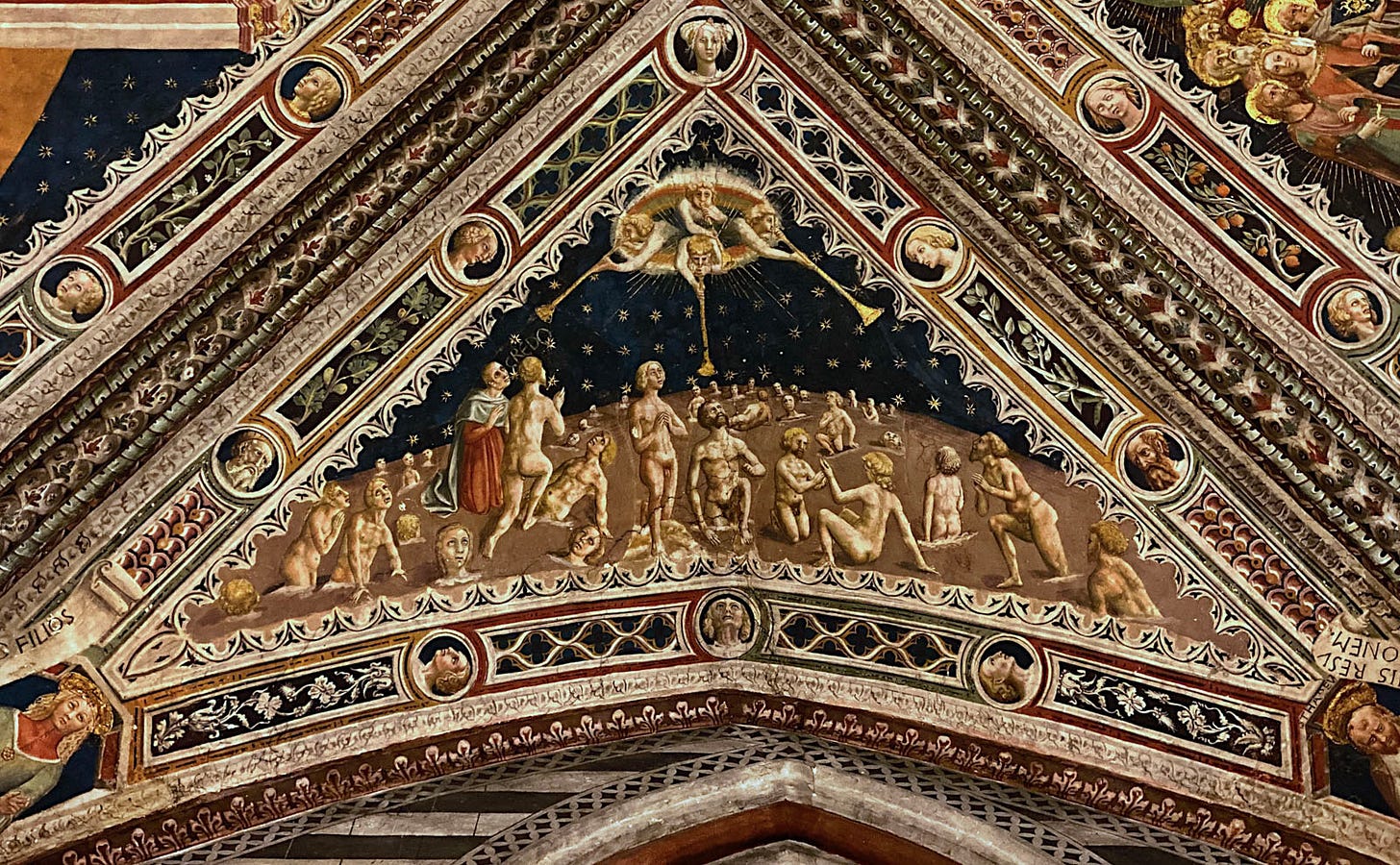

The baptistry, built c1320 under the chancel and accessed from the east side of the cathedral, is perhaps my favorite part of the whole place. It’s hard not to be enchanted by all the amazing frescoes (figures 1, 5, 9 & 11), of course, and the smaller scale versus the cathedral proper lets you get reasonably close to see them.

The ceiling frescoes are largely the work of Lorenzo di Pietro (aka “Vecchietta”) and were done between 1447 and 1450. Most of the wall frescoes show the miracles of St Anthony of Padua and were done in c1460 by Benvenuto di Giovanni.

When I visited, the famous baptismal font was in process of being restored, and so it was closed off and only partly visible through some windows. The font was a collaborative work in which many well known artists contributed bronze panels between 1417 and 31. The baptism of Christ (figure 10) is by Lorenzo Ghiberti.

The white marble of the west facade really gleams in the Tuscan sun, as does the gable mosaic (figures 13-14), which shows a Coronation of the Virgin. The oculus below that has a couple sculpted Virgin Marys in the central top and bottom positions, and is surrounded by some three dozen prophets and patriarchs.

Work on the facade occurred in two stages, from about 1284-1317 and then again from maybe the 1330s to 1360s.The style features a mix of Romanesque, Gothic, and Classical influences.

Most of the lower sculptures were overseen by Giovanni Pisano, who oversaw all of the the first phase work. Copies are in place now, but many of the original sculptures can be seen in the on-site museum (see the “In Detail” section below). The upper work was overseen by Giovanni di Cecco — is more ornate and properly “Gothic,” and was likely inspired by Orvieto Cathedral (which we explore later in this series).

The black and white banding that we saw on the exterior (figures 3 & 12) becomes at least as striking on the inside, especially in the nave.

Figure 17, looking down at the nave, shows the large panels of figurative images in the flooring. These are spectacular and are shown in more detail in the “In Detail” section below.

Separating the lower level from the clerestories is a cornice studded with some 172 busts of popes, starting with St Peter and ending with Lucius III (Pope from 1181-85). And in the spandrels on either side of the arches are the busts of 36 emperors. (Figure 18 shows all this best).

The clerestory level, along with the upper portion of the west facade, are the most properly “Gothic” portion of the cathedral, with the pointed arches and windows, clustered columns, tracery and stained glass.

Figures 21-24 show the crossing and chancel/choir, including the very irregularly shaped dome.

You may noticed that a lot of the photos above came from the clerestory level of the cathedral. Getting up here requires a special ticket and a timed entry for a tour, but it is well worth it and definitely recommended if you visit here.

Outside the main floor plan of the cathedral cross you find some later additions: side chapels in the Baroque style with statuary by Donatello and Bernini, and the Renaissance Piccolomini Library (figures 6 & 26).

Under the cathedral proper, near the baptistry, you can enter a series of spaces that must have once been the original chancel and north transept of the previous cathedral. There’s a series of 13th C frescoes here that were only discovered in 1999, and they are in remarkably good shape and still incredibly vibrant (figures 29-30).

In Detail

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Dates: 28-29 October 2021

Ticketing is complex, but my recommendation is to buy a ticket that allows entry to everything, and if you have an option for a guided tour up in the clerestory level, take it.

Siena is typically just visited as a day trip, but there is a lot to do here — a medieval painting museum and the Palazzo Pubblico, for starters — and spending a night or three will allow you to fully explore the place. Busloads of daytrippers crowd the streets most of the day, but if you spend the night you can explore in peace in the morning and evening.

Siena Cathedral represents one of Italy's most successful adaptations of Gothic architecture to regional tastes and building traditions. What it may lack in the soaring verticality of northern Gothic cathedrals, it more than compensates for with its remarkable synthesis of architectural styles, spectacular decorative program, and the ingenious way it accommodates its hillside setting.

Fantastic essay about this gorgeous cathedral! I’m stunned to learn how fast the majority of the cathedral got built in the 13th C 🤯 Really speaks to the wealth of the city and their choice to invest in such a showstopper of a house of worship. Totally agree that the clerestory tour is well worth it. Learned tons and the views are amazing. The thing that impresses me most is your photography skills - while this cathedral is eminently photogenic, it’s also challenging to convey the impact it has on the viewer. You capture that awe-inspiring experience so well. Also, how did you manage to avoid the crowds in your shots?!? The cathedral was heaving when I visited. Thank you so much for this treat! 🙌