(8 min read) York Minster — number 31 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — represents the pinnacle of English Gothic unity in the north.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: York Minster

Official Name: Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York

Location: York, UK

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: c1220-1472

Why It’s Great

York Minster is the North’s great Gothic cathedral. No other English church north of the Trent rivals its size, clarity, or consistency. Despite a two-century construction period, it is not a patchwork of eras but a unified vision in stone and glass. Its vast nave, soaring choir, and immense east window form one of the most coherent expressions of English Gothic from the Early to Perpendicular eras.

Why It Matters: History and Context

A series of previous churches occupied the site of York Minster for some six centuries before the Gothic structure we see today.

The Christian history of York begins in 627 CE when King Edwin of Northumbria was baptized in a small wooden church here. This was replaced by a more substantial stone structure dedicated to St Peter, which was expanded over the centuries but suffered extensive damage from fire and during the Danish invasions.

The Norman conquest of 1066 brought dramatic changes to England's religious landscape and and led to the destruction of York's existing church. In 1080, Archbishop Thomas of Bayeux began construction of a new Norman cathedral at York. While nothing remains above ground of this Romanesque structure, the crypt does reveal some of its form (figures 26-27).

The York Minster we see today began in 1220, when Archbishop Walter de Gray — inspired by the emerging Gothic style he had witnessed at Canterbury and in France — initiated construction of the transepts (figures 3, 6, 17-19), both completed in the 1250s.

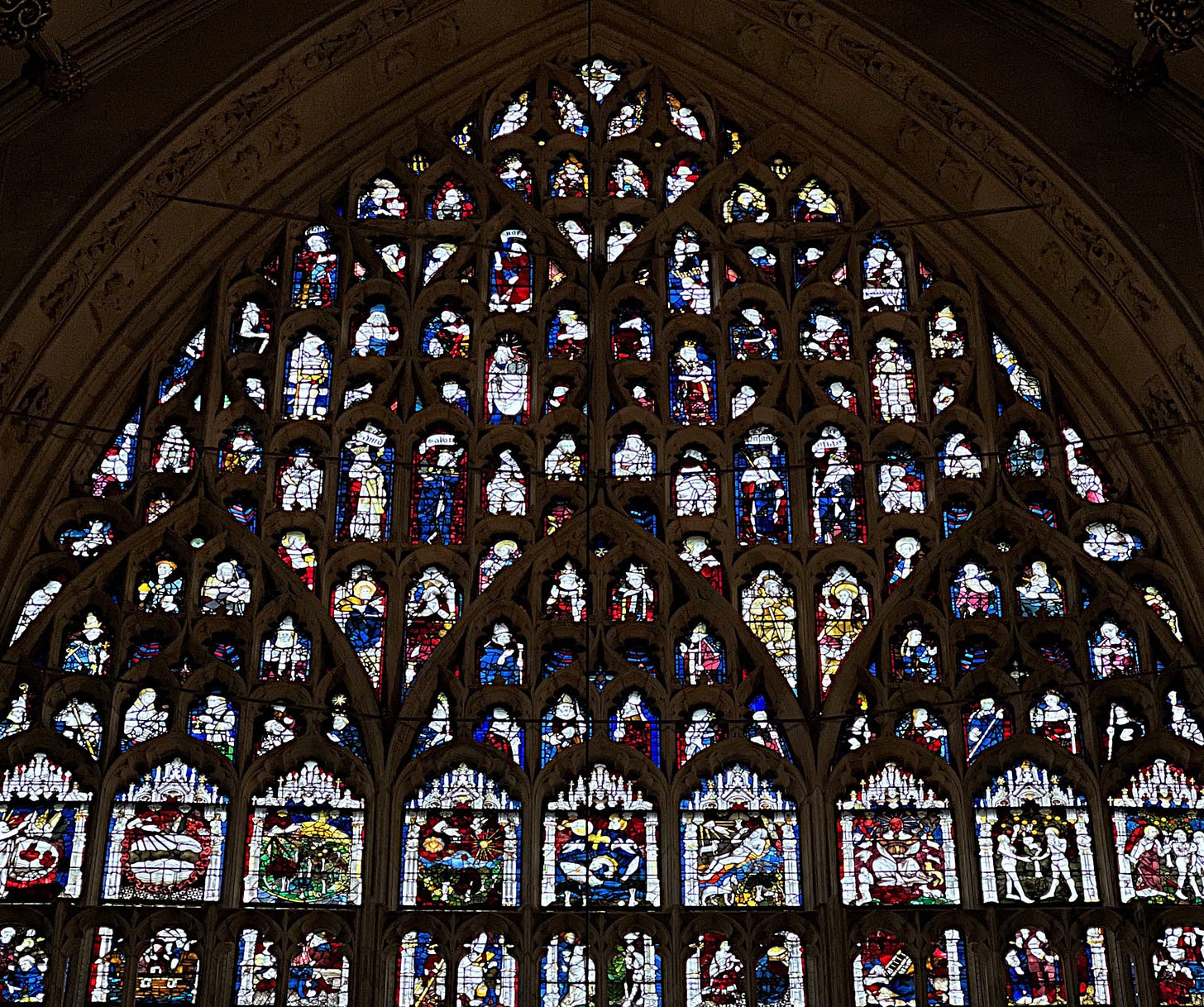

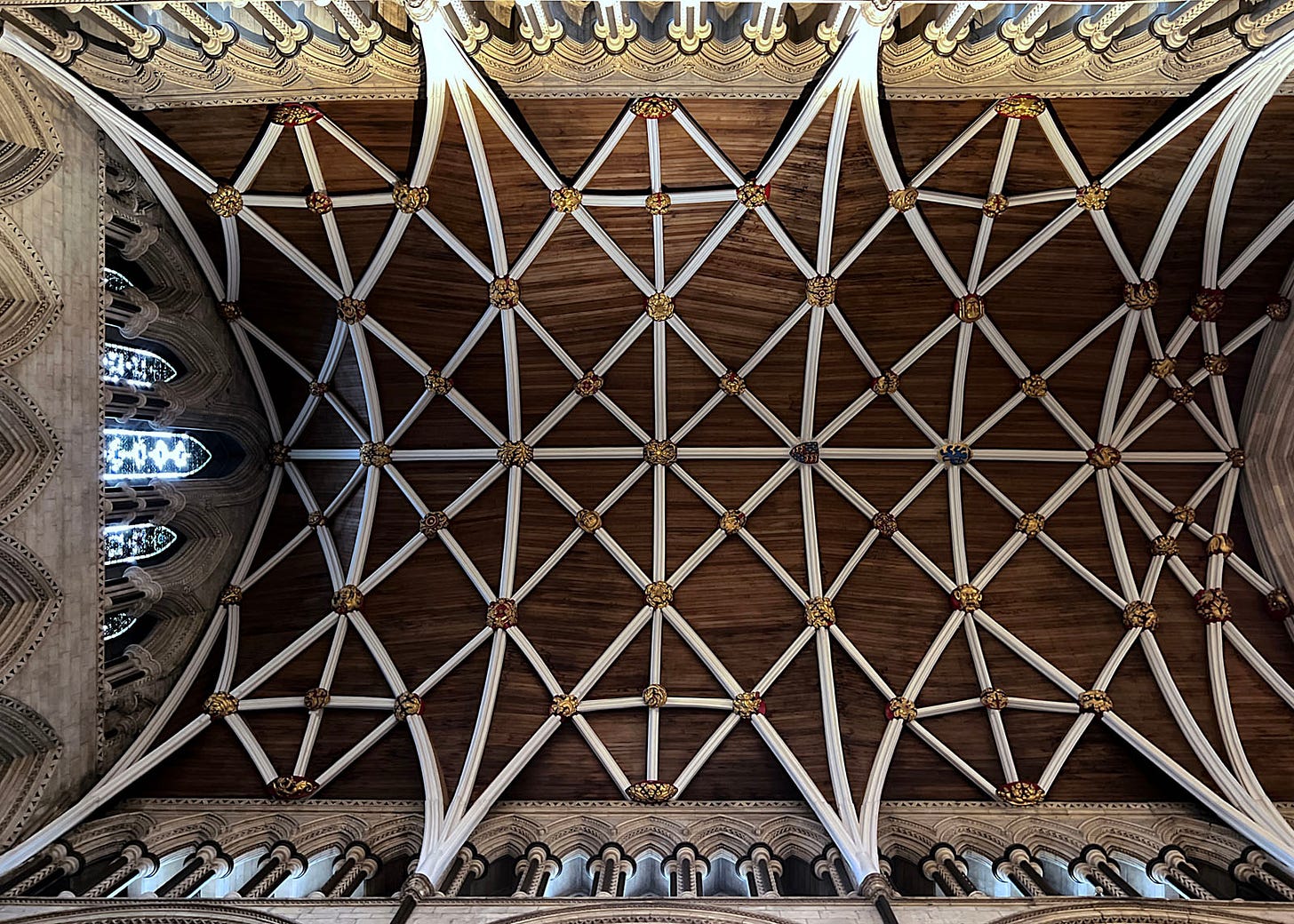

Between 1280 and 1350, the nave (figures 1, 13-16) was entirely rebuilt in the Decorated Gothic style. Its width and elegant proportions create a distinctly English interpretation of Gothic, prioritizing horizontal development and harmonious proportions over the extreme verticality found in French cathedrals of the period.

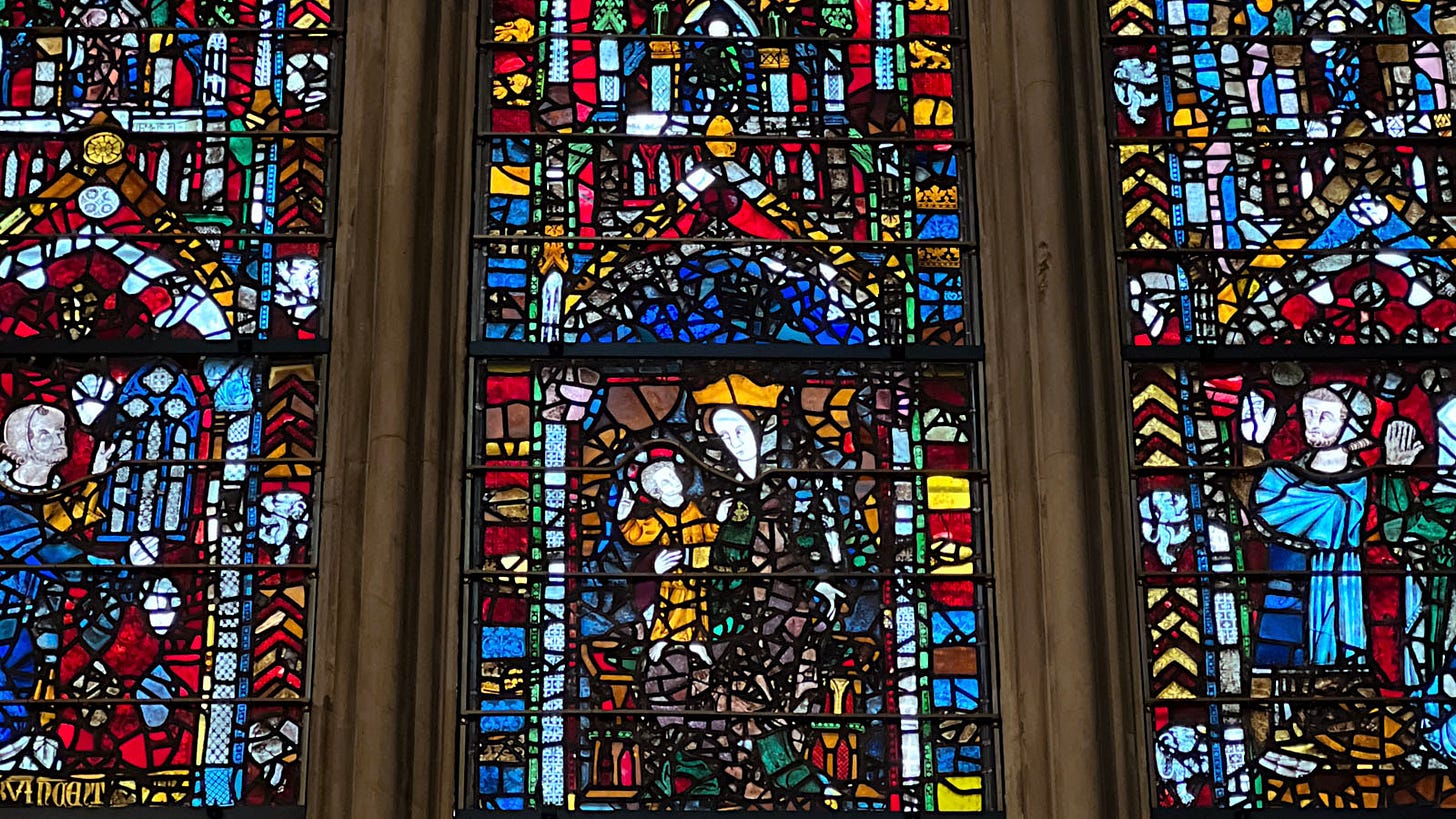

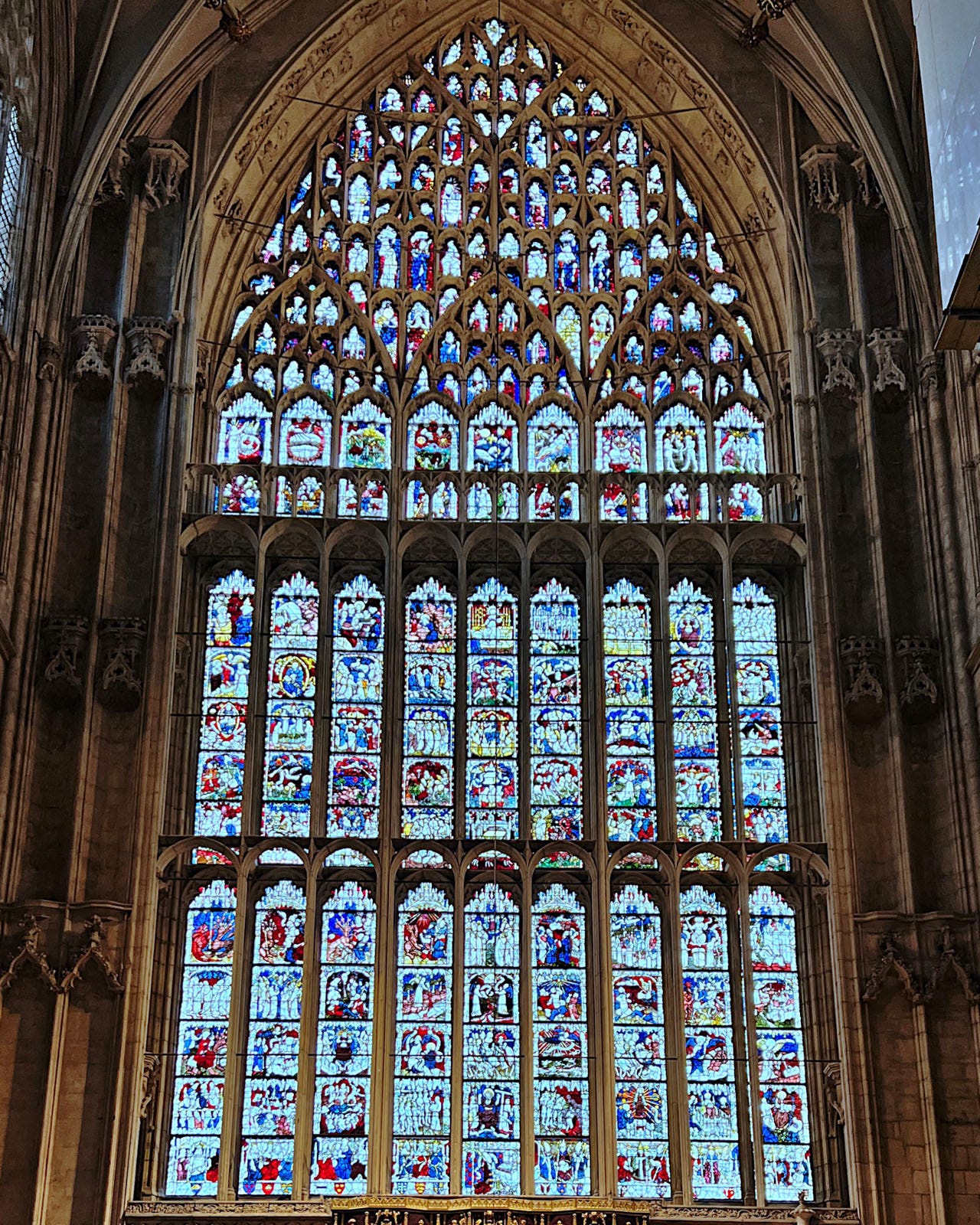

The eastern end of the cathedral (figures 22-25), including the choir and presbytery, was reconstructed between 1361 and 1405 in the Perpendicular Gothic style. Master mason Robert Prentys and master carpenter William Hyndeley ensured the new choir maintained coherence with the earlier sections while also introducing signature elements of Perpendicular. The magnificent East Window, completed in 1408, remains the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the world.

The final major Gothic work here was the central (figure 2) and western towers, built from the 1420s to 1472. The cathedral was finally consecrated in 1472, marking the completion of a building campaign spanning two and a half centuries.

York Minster's history reflects the city's importance as England's second city and the ecclesiastical capital of the North. As the seat of the Archbishop of York (the Primate of England, second only to Canterbury), the cathedral stood as a symbol of northern power. This regional significance meant the Minster received patronage not only from the Church but from northern nobles eager to display their piety and wealth.

The English Reformation brought dramatic changes to the Minster's function and appearance. In the 16th century, much of its medieval statuary was destroyed, and the elaborate wall paintings were whitewashed. The cathedral narrowly escaped the wholesale destruction that befell many English monasteries, partly due to its status as a secular cathedral rather than a monastic institution.

During the English Civil War of the 1640s, York was besieged by Parliamentary forces, but the Minster was — unlike many cathedrals across England — largely spared from damage. The 18th century brought a period of relative neglect, though the Minster remained an important center of worship and civic pride. The 19th century saw extensive restoration work, sometimes heavy-handed by modern standards but essential for the building's survival.

More recent times have witnessed both tragedy and triumph. A devastating fire in 1984, caused by a lightning strike, severely damaged the south transept roof. The ensuing restoration project became one of Britain's largest, demonstrating modern craftsmanship that honored medieval techniques. Between 2007 and 2018, a major conservation project restored the East Window's stained glass to its former glory.

Today, York Minster stands not only as a triumph of medieval architecture but as a testament to continuous care and adaptation. Its Gothic splendor remains remarkably unified, despite the centuries of construction, restoration, and change — a quality that sets it apart from many of its northern contemporaries and earns it a distinguished place in this countdown of Gothic architecture.

Photo Tour

I spent an entire week in York in November 2022, and there was not a single day without fog. While that hindered proper documentation of the exterior (figures 7-12), it did allow me to get some wonderfully moody black-and-white shots, six of which are shown in the “In Detail” section below.

The nave at York is broad, bright, and graceful — a Decorated Gothic space that avoids visual clutter while still impressing with its scale and ornament. These photos show the harmony of proportion, the delicate rib vaulting, and the intricately carved bosses that quietly assert the craftsmanship of the 14th century.

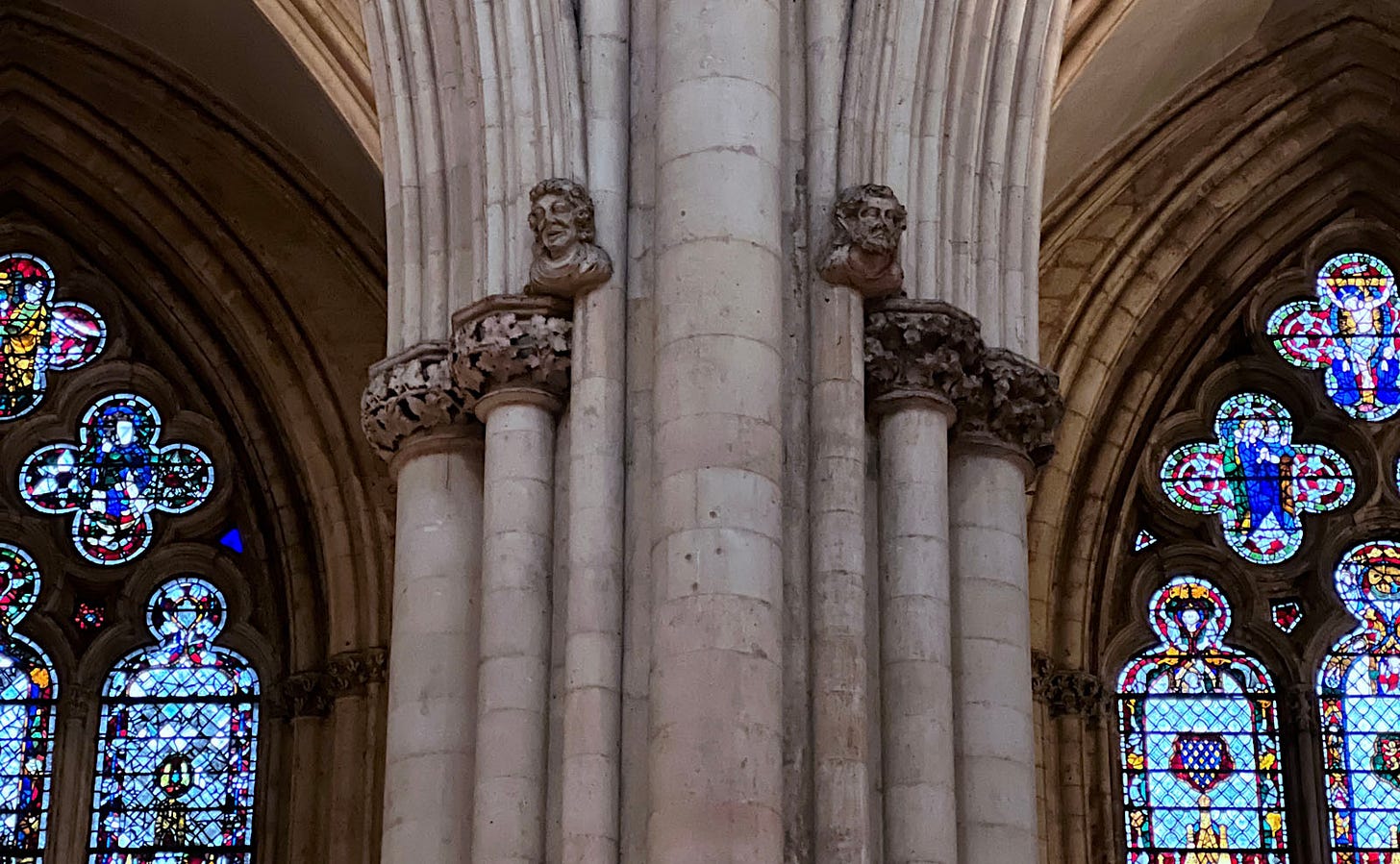

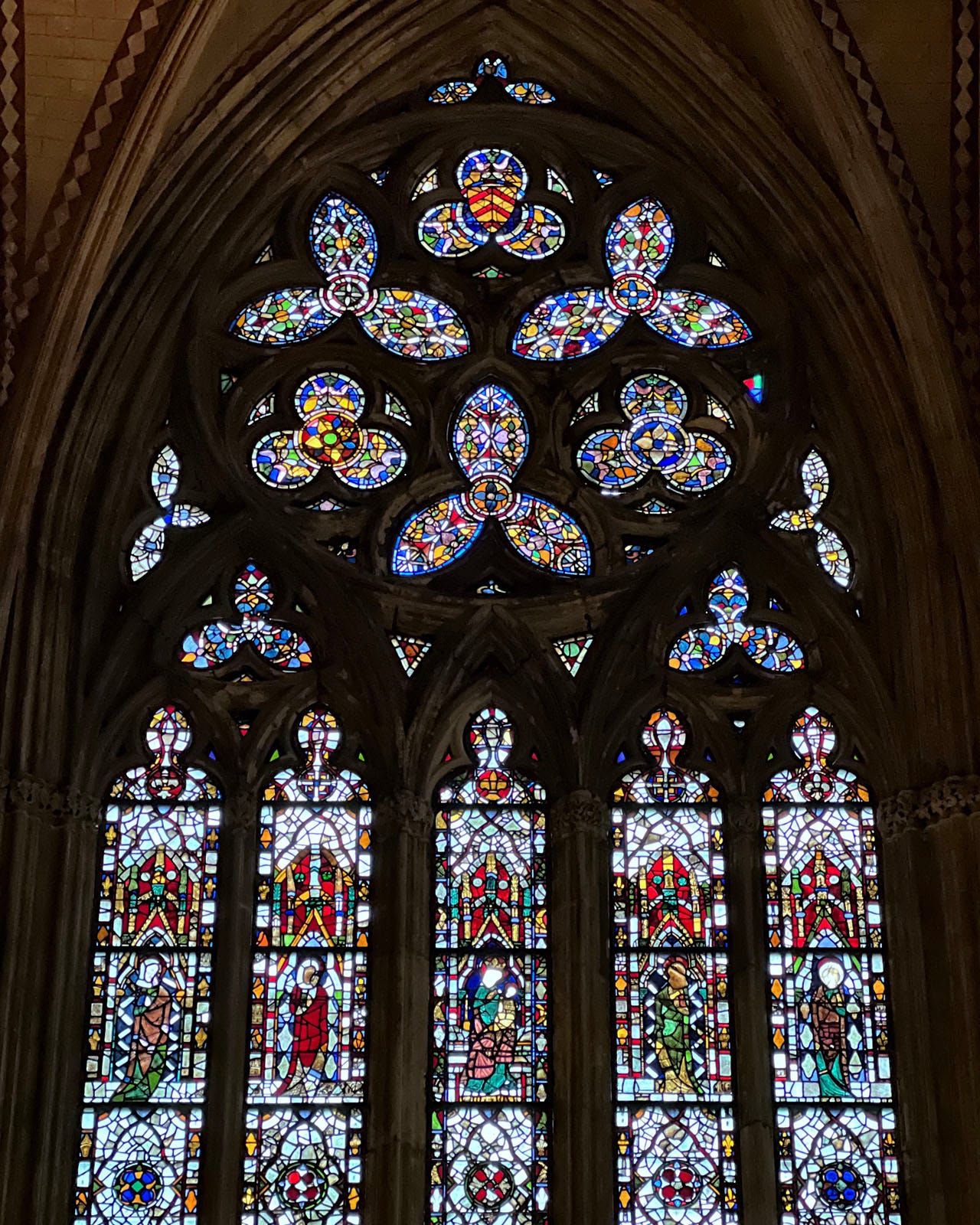

The transepts were the first Gothic parts of the new cathedral, built in the mid-13th century. Their window schemes are notably different — the north with the famed “Five Sisters,” the south with a small rose above lancets.

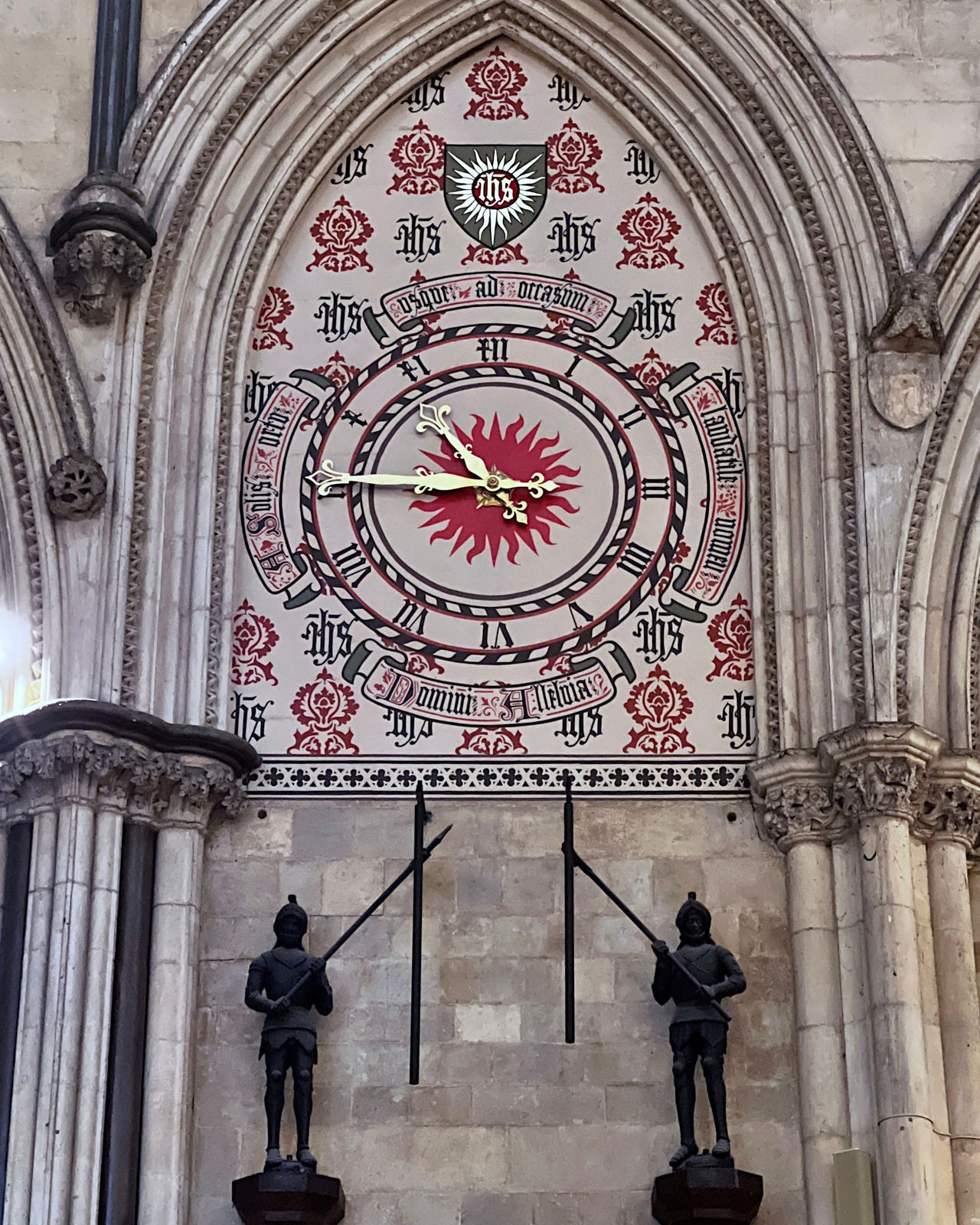

Two elements stand out at the crossing. The Hindley Clock — in the north transept adjacent to the crossing — combines an 18th-century mechanism with a Victorian face, flanked by two 16th century carved figures, Gog and Magog, who strike the quarters.

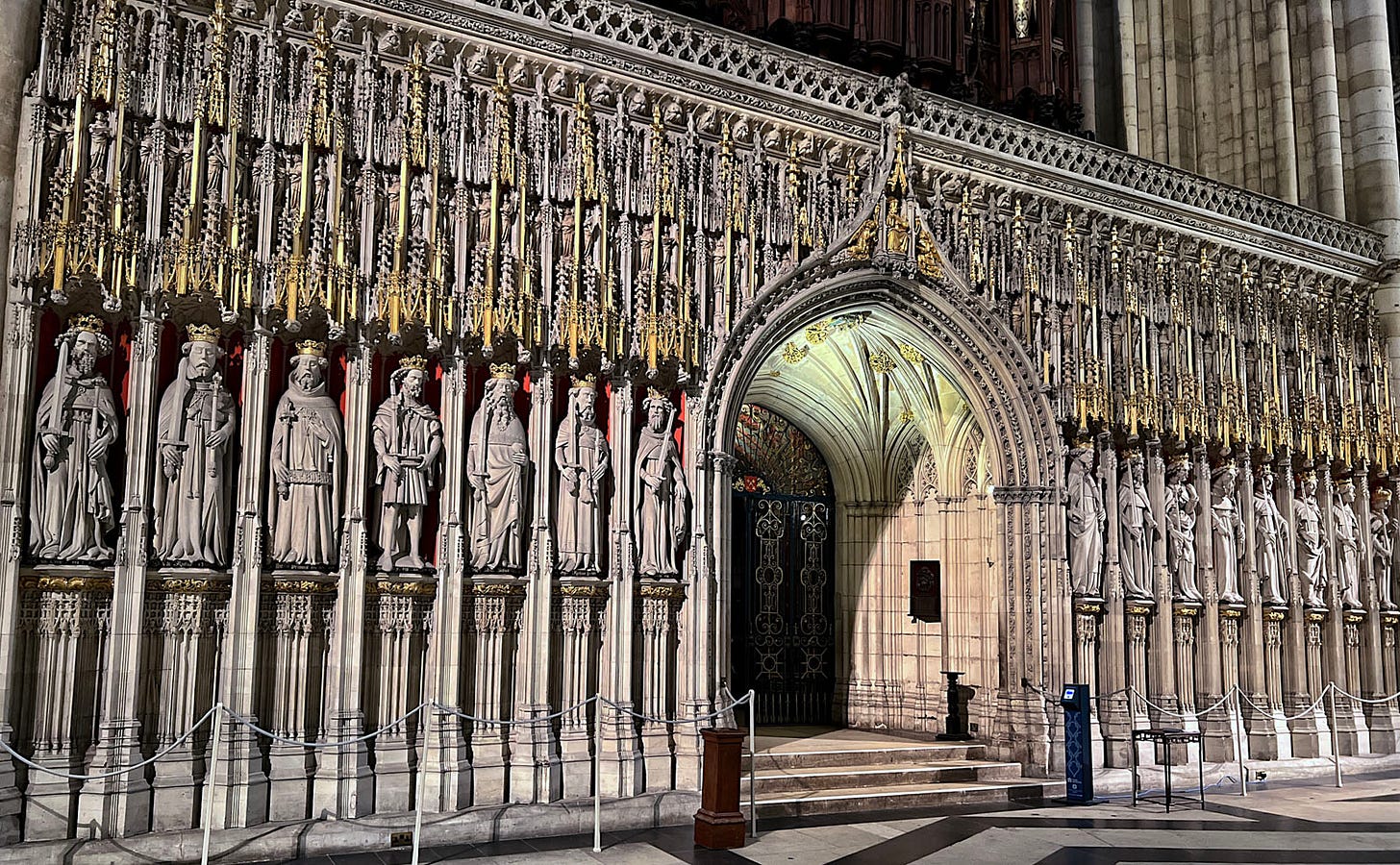

At the crossing the typical medieval “rood screen” has been transformed into a a late medieval masterpiece of English sculpture, featuring all the English kings from William the Conqueror to Henry VI line its niches, blending dynastic propaganda with architectural framing. (See “In Detail” below for more shots of the screen).

Moving into the choir, the architecture shifts to Perpendicular — more linear, more vertical. But the harmony with earlier sections is preserved. These views show how the space flows toward the immense East Window, and how side aisles and choir stalls maintain a unity of rhythm despite stylistic evolution.

Underneath the east end of the cathedral is the crypt (figures 26-27) and undercroft. The crypt includes some remains of the Norman church and the tomb of St William of York, archbishop who died in 1154. The undercroft has a small museum with a number of interesting artifacts; one of the embeds in the “In Detail” section below feature pieces from it.

York’s Chapter House (figures 8, 28-30) was built from c1265-c95 and is unique in being an octagonal shape without a central column, a structural triumph for the time. Its niche benches on the walls also feature some wonderful carvings, which are explored in one of the “In Detail” embeds below.

In Detail

More information about and photos of the Chapter House, King’s Screen, and crypt are below. But first some mood shots:

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 14 November 2022

York Minster charges for entry unless you're attending a service. The undercroft museum is small but worthwhile, and you can also climb to the roof and central tower for a fee. Just hope for less fog than I had.

York itself is worth a stay of at least a few days, and walking its city walls will provide some excellent views to the Minster’s exterior.

Few cathedrals reward repeated visits as richly as York Minster — not just for its scale or glass or stone, but for the way it anchors the city around it, a Gothic heart still beating at the center of the North.

Wonderful work as always Ben, thank you.

Brilliant - love it! 👍👏🫡