(8 min read) Krakow’s St Mary’s Church — number 30 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — showcases a spectacular revivalist renovation and contains the rightly famous Veit Stoss altarpiece.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: St Mary’s Church

Official Name: Kościół Wniebowzięcia Najświętszej Marii Panny (Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary)

Location: Krakow, Poland

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: c1220-c1480; interior 1887-91

Why It’s Great

St Mary's showcases one of Europe's finest Gothic Revival interiors, where Jan Matejko's brilliant polychrome murals and Wyspianski/Mehoffer's jewel-toned stained glass create an immersive medieval atmosphere that feels both authentically Gothic and distinctly Polish. The church also houses Veit Stoss's magnificently massive wooden altarpiece, one of the greatest works of late Gothic sculpture.

Why It Matters: History and Context

By all rights, St Mary’s Church in Krakow should be around 40th in my countdown, not at 30. I am not sure what I was thinking when I ranked it so highly back in December when I put my list together — except that the stunning interior I had seen just two months earlier left quite an impression. If and/or when I turn this countdown into a book, I’ll adjust things.

In the meantime, I will simply lean on the subjectivity of my “artistry” criterion (see my list of criteria in the introduction to this series), as well as “regional and stylistic context,” to justify the placement. Because the Revivalist interior is gobsmackingly gorgeous. And while Gothic Revival buildings are excluded from my survey, I do include original Gothic buildings with Revivalist renovation work.

With those caveats out of the way, let’s discuss the church itself and its history.

St Mary’s Church fronts the northwest corner of Krakow’s main market square, where a Romanesque church had existed since the early 13th century. The current Gothic structure began around 1290 and was consecrated in 1320. Over the next two centuries — particularly from 1355-65 during Casimir the Great’s reign, and again in the 15th century — major changes and additions took place.

The asymmetrical twin towers — one of Krakow’s most recognizable features — reflect this extended building campaign. The taller north tower, completed in the early 15th century, served as the city’s watchtower and is famous for the hourly trumpet call (hejnał) that still echoes across the square today. The shorter south tower housed the church bells.

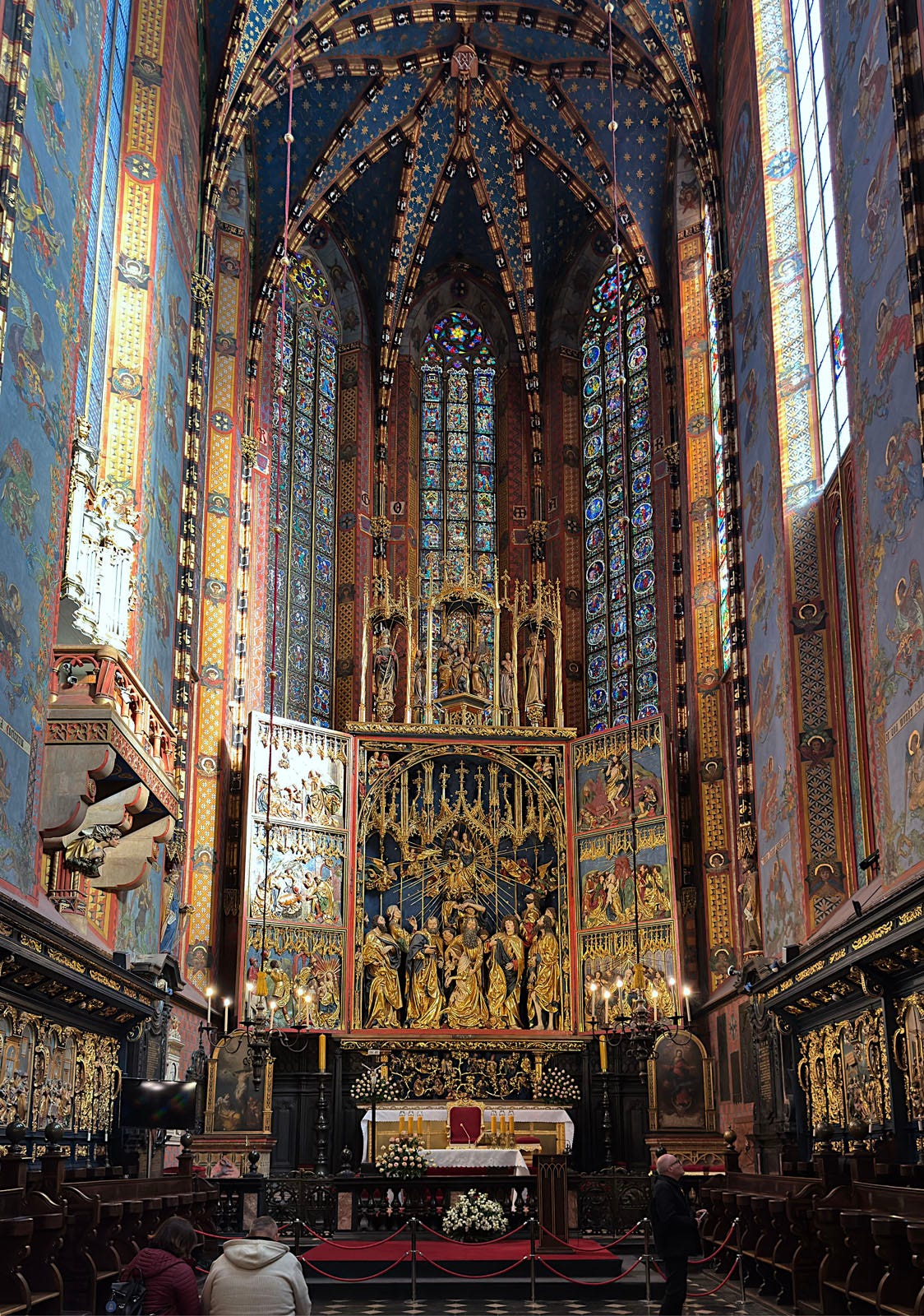

The interior took shape gradually through the 14th and 15th centuries, culminating in the installation of Veit Stoss’s magnificent wooden altarpiece between 1477 and 1484 (figures 22 & 25, and “In Detail” below). This German master sculptor created what many consider the finest Gothic altarpiece in Europe — a towering polychrome masterpiece depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary.

The church’s Gothic character was essentially complete by 1480, featuring the characteristic pointed arches, ribbed vaulting, and soaring proportions we associate with the style.

But like many medieval churches, St Mary’s underwent significant changes in subsequent centuries. The Baroque period brought particularly dramatic alterations in the mid 18th century, when the interior was overlaid with ornate decorations, curved forms, and gilded elements that completely obliterated the Gothic atmosphere. Some two dozen Baroque side altars were installed, and elaborate stucco work masked much of the original stonework. For over a century, visitors experienced a heavily Baroque church that bore little resemblance to its medieval origins.

This all changed dramatically in the 1880s, when Krakow’s cultural elite — living under Austro-Hungarian rule during Poland’s partition — decided to reclaim their Gothic heritage. The comprehensive renovation from 1887 to 1891, led by architect Tadeusz Stryjenski, aimed to strip away inappropriate Baroque additions and restore the church’s medieval character. This wasn’t mere preservation but creative revival: where original Gothic elements had been damaged or lost, they were carefully recreated based on surviving fragments.

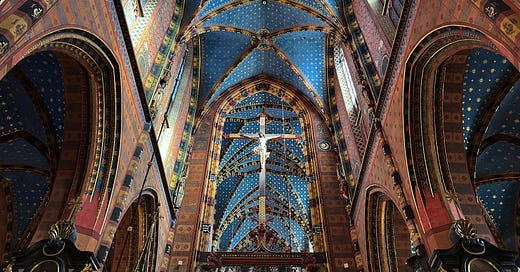

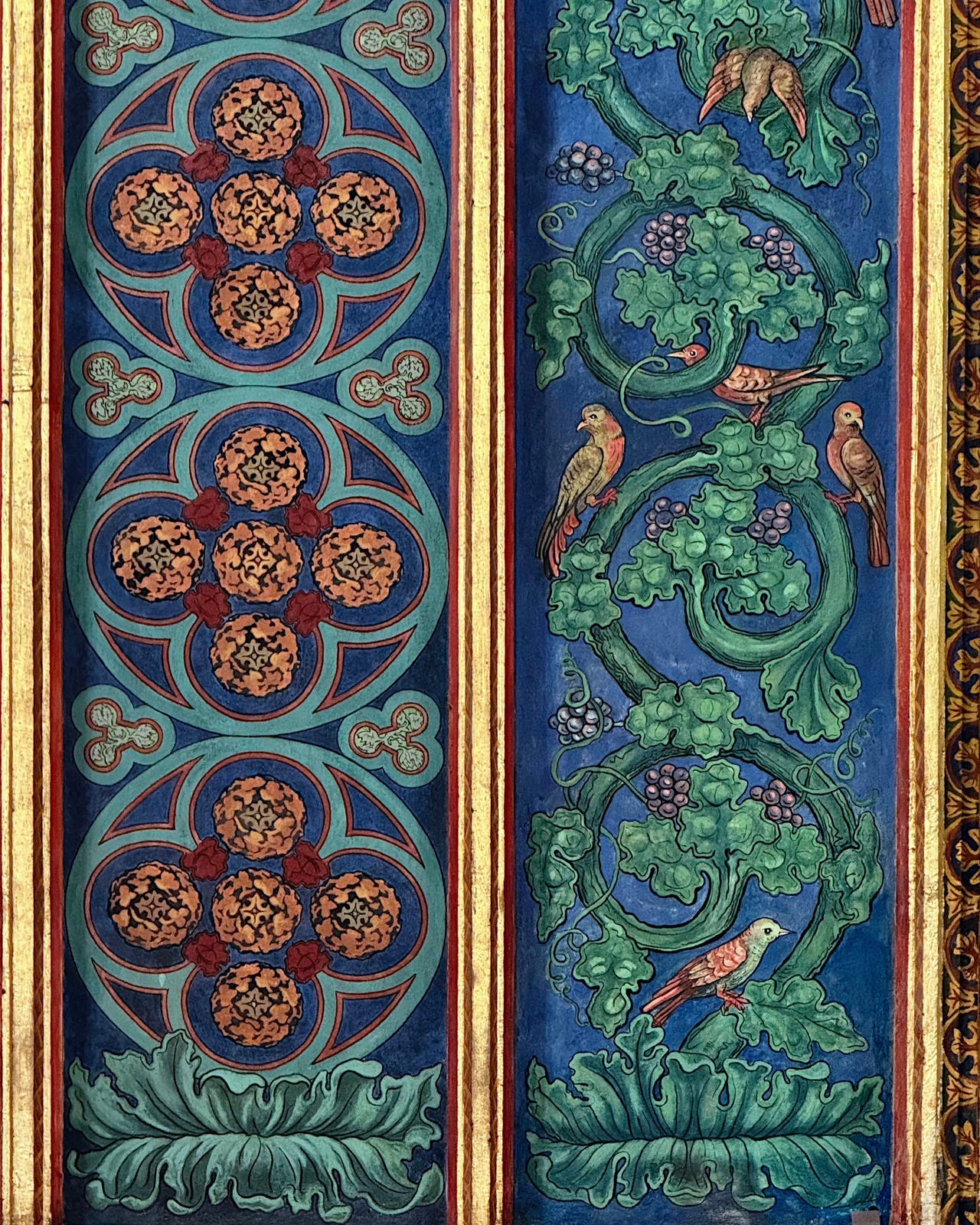

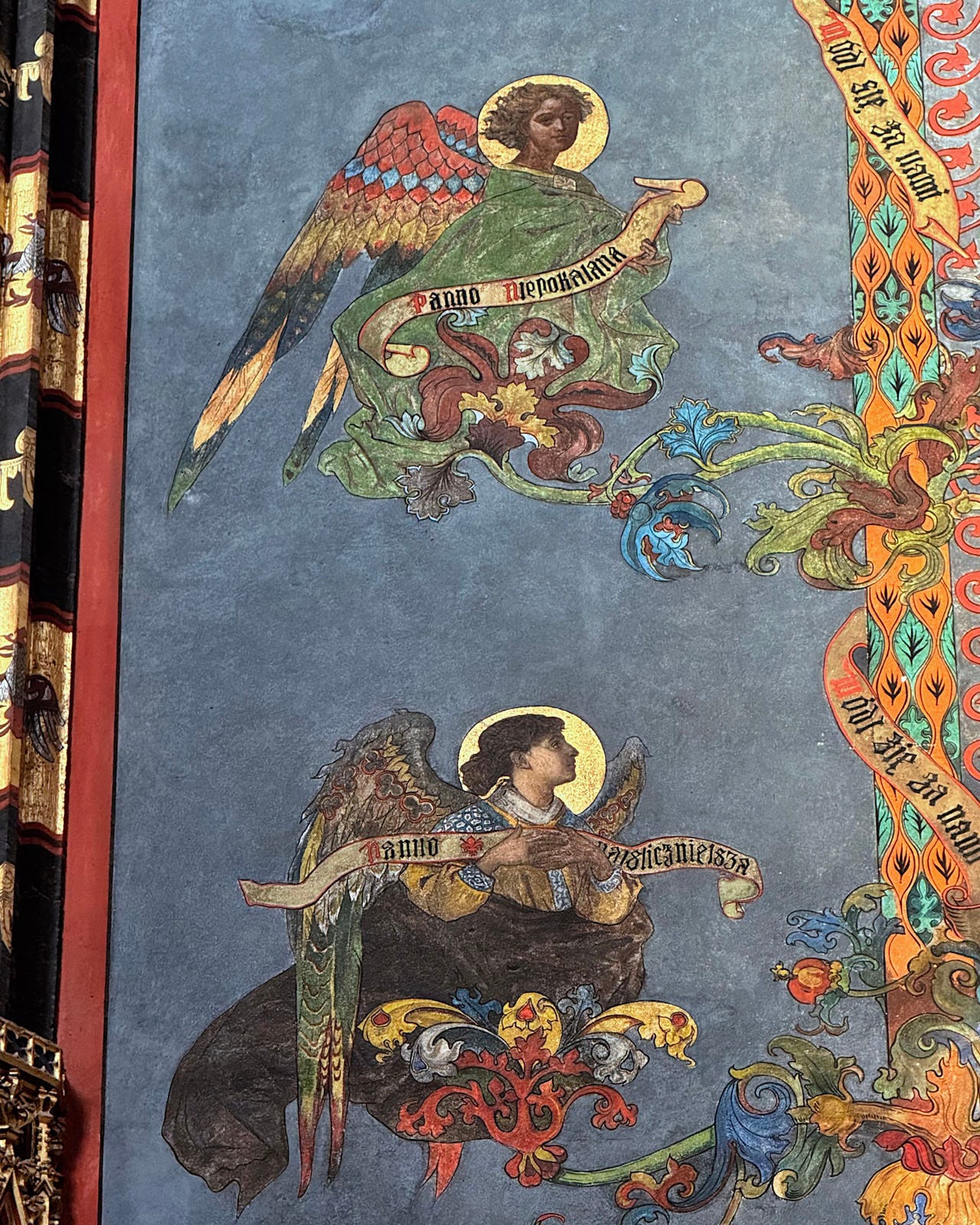

The transformation was spectacular. Jan Matejko, Poland’s most celebrated painter, designed an ambitious polychrome program that covered virtually every interior surface with vibrant murals, biblical inscriptions, and ornamental patterns in medieval style. The vaulted ceiling became a deep blue field scattered with golden stars, evoking the heavens above. Meanwhile, Stanislaw Wyspianski and Jozef Mehoffer, created stunning new stained glass windows that flooded the space with jewel-toned light.

Crucially, this wasn’t the fantastical Gothic Revival often common in 19th-century Europe. Rather than inventing medieval imagery from romantic imagination, Matejko and his team drew carefully from actual surviving Gothic precedents. Many details were discovered underneath the Baroque renovations which provided guides for their work. In addition, the the starry ceiling echoes Sainte-Chapelle in Paris while the overall polychrome approach follows patterns found in authentic medieval churches across Europe. This archaeological sensibility — part of the broader “Vistula Gothic” movement — represented a more scholarly approach to revival than the theatrical fantasies of Pugin or Gilbert Scott.

The political context demanded authenticity: Gothic was promoted as “the most appropriate expression of the venerable national Polish style in opposition to the Byzantine Revival in church architecture officially endorsed by imperial Russia.”

Today's visitor experiences this 1890s vision almost unchanged. The neo-Gothic interior remains one of the most visually stunning church interiors in Europe, where Matejko's brilliant polychromy and the artists' stained glass create an immersive environment that feels both authentically medieval and distinctly Polish.

Photo Tour

Krakow’s medieval center retains much of its old charm, and Rynek Glowny — the large town square bisected by a medieval/Renaissance cloth hall turned museum — is its focus. In turn, the focus of Rynek Glowny is St Mary’s. Figures 4 & 7-9 show the exterior.

Figures 5 & 10-14 show the nave.

The side aisles (figures 15-17) take on essentially the same design patterns as in the nave.

While the painting schemes of the nave, side aisles and chancel retain an authentic medieval feel, the artists took more freedom in the side chapels, it seems to me, as you can seen figures 18-20.

As splendid as the nave’s interior is, things are taken to another level — with even more intricate designs and paintings — in the chancel and apse, the real heart of worship here.

While dark Baroque elements still line much of the ground level, as your eye is drawn upward you encounter a vision of color and light.

In Detail

Here is a Note with six photos of the Veit Stoss altarpiece:

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Dates: 15 & 17 October 2024

There is an entry fee for tourists, and the hours here for visitors are limited, so check in advance. Krakow itself is a wonderful city worth at least a few days of your time. In addition to a several more Gothic churches and probably a dozen sights within the old medieval city section, there’s the Wawel Castle complex just outside it — itself worth the better part of a day.

St Mary's stands as both a masterpiece of archaeologically informed Gothic Revival and a showcase for Poland's greatest medieval treasure, making it essential viewing for anyone interested in either Gothic art or 19th-century cultural nationalism.

I only had pictures with a very bad quality from my visit, so thank you for all the detailed pictures!

Great info! Lovely photos! Thanks!