(7 min read) St Stephens Cathedral — number 29 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — embodies Vienna’s role as Europe’s great crossroads.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Stephansdom (St Stephen’s Cathedral)

Official Name: Dom- und Metropolitankirche zu Sankt Stephan und allen Heiligen (Cathedral and Metropolitan Church of Saint Stephen and All Saints)

Location: Vienna, Austria

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1230-1511

Why It’s Great

St. Stephen’s Cathedral embodies Vienna’s role as Europe’s great crossroads, where Germanic Gothic traditions merged with imperial ambition to create a uniquely Central European architectural synthesis. As the ceremonial heart of the Habsburg Empire for centuries, it represents not just exceptional Gothic craftsmanship, but the political and cultural forces that shaped modern Europe.

Why It Matters: History and Context

This is the second post in a row requiring a mea culpa (though I’m pretty sure it will be the last needed in this series). For Stephansdom, the apology is about my photos — both quantity and quality.

Usually I struggle to winnow down to thirty photos (my semi-arbitrary maximum), especially as I climb higher in this list and want to show you increasingly beautiful things. But I only have twenty photos of St. Stephen’s worth sharing, and many don’t meet my usual standards. There are two main reasons for this.

First, I visited St. Stephen’s in summer 2022, before I’d decided that fall to seriously document Gothic architecture. True, six other buildings on my list — several already posted — were also visited before Stephansdom, and I managed full photo essays for those (I’ve long been obsessive about architectural photography).

Second I neglected St. Stephen’s because I was fed up with summer crowds being herded around in giant tour groups, church access was limited and weirdly ticketed (like five different tickets required), and I simply wasn’t in the mood to photograph much on either day I visited.

Excuses, excuses, I know. But that’s why I’m apologizing in advance. Stephansdom remains a great church, and this is still a solid essay with plenty of good shots. The photos just don’t meet my usual standards, and I wanted to explain why.

The cathedral we see today represents centuries of ambition, destruction, and renewal at the heart of European power.

The earliest church on this site dates to the 12th century, built during the reign of Leopold VI as Vienna emerged as a crucial trading hub between East and West. But it was the Habsburgs’ rise to prominence that transformed a modest parish church into one of Europe’s most significant Gothic monuments.

Construction of the Gothic cathedral began in earnest around 1230, though the building we see today largely reflects work from the 14th and 15th centuries. The western facade, with its massive Romanesque towers known as the Heidentuerme (“Pagan Towers”), survives from the earlier structure, creating that distinctive hybrid character that marks so many great medieval cathedrals. These towers were deliberately preserved — not from sentimentality, but because they already functioned as powerful symbols of Christian authority in a contested borderland.

Gothic transformations accelerated dramatically after 1359, when Duke Rudolf IV — known as “the Founder” — launched an ambitious rebuilding campaign designed to rival the great cathedrals of France and the Holy Roman Empire’s western territories. In this effort, Rudolf wasn’t just building a church; he was making a statement about Habsburg legitimacy and Vienna’s growing importance. The soaring nave, completed in the late 14th century, and the magnificent south tower (the Steffl), finished around 1433, represent High Gothic architecture adapted to local materials and Central European sensibilities.

What makes St. Stephen’s architecturally fascinating is how it reflects Vienna’s position as an imperial crossroads. Germanic Gothic traditions merge with Eastern European and even Ottoman influences — a reminder that Vienna stood on the frontier between Christendom and the Ottoman Empire.

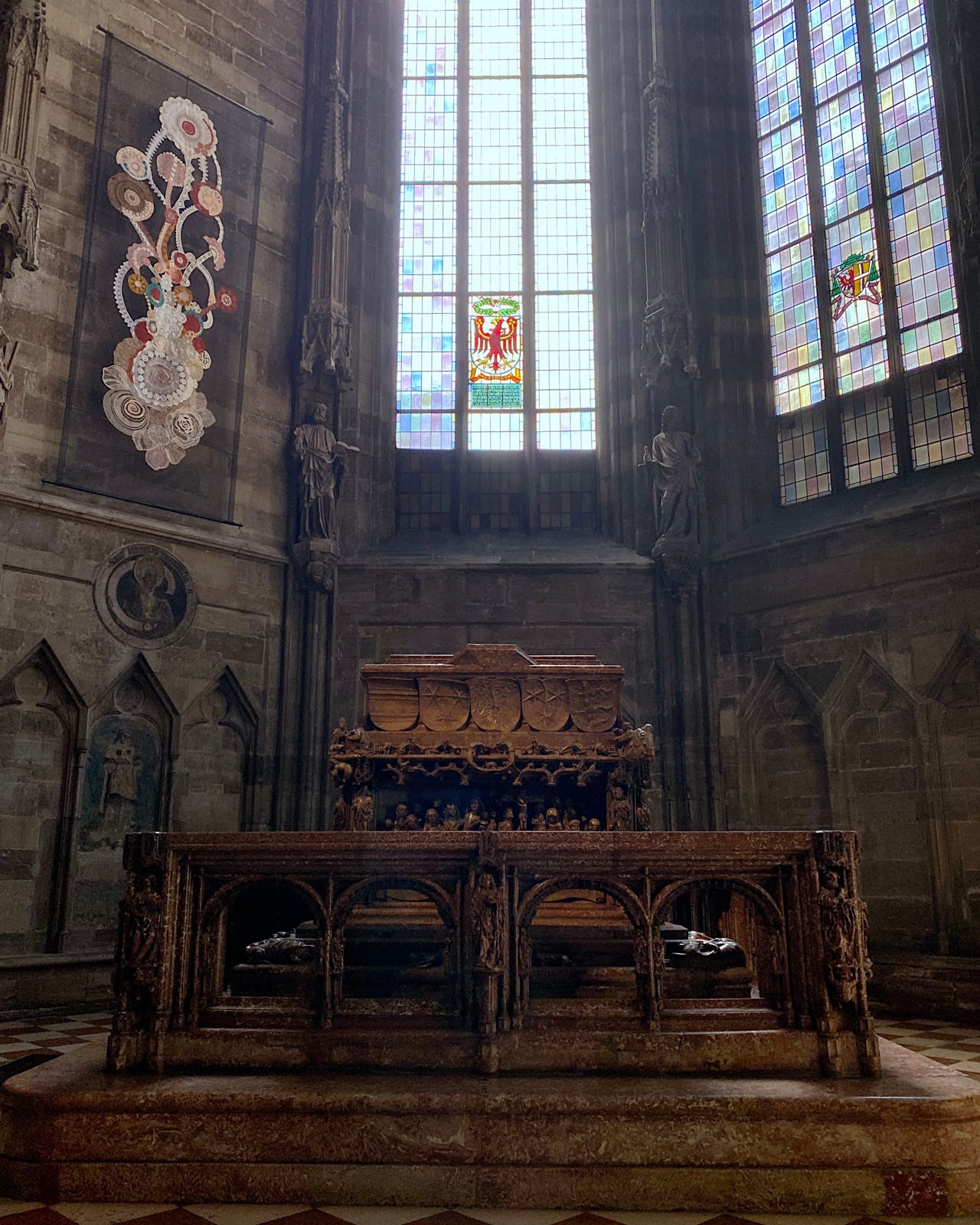

The building served as the ceremonial heart of the Habsburg Empire for centuries. Here, emperors were crowned and buried, royal marriages celebrated, and Te Deums sung for military victories. The cathedral witnessed Frederick III’s coronation as Holy Roman Emperor in 1452, and later hosted ceremonies marking Habsburg triumphs over the Ottomans. The “Ducal Crypt” underneath the chancel became a Habsburg mausoleum, housing the internal organs of emperors in elaborate urns — a macabre but deeply symbolic practice linking the dynasty to this sacred space.

Post-medieval additions generally respected the Gothic character, though Baroque altars and furnishings were added during the Counter-Reformation. The real trauma came in 1945, when Soviet artillery and a devastating fire destroyed much of the roof and interior. The cathedral’s resurrection became a symbol of Austrian renewal — the entire nation contributed to reconstruction efforts that lasted until 1962.

Today’s St. Stephen’s represents both medieval ambition and modern restoration techniques. While purists quibble with some 20th-century interventions, the rebuilding preserved the cathedral’s essential Gothic character while adapting it for contemporary use. The result is a building that embodies Vienna’s role as a bridge between worlds — architecturally, culturally, and politically — making it a worthy representative of Gothic architecture’s adaptability and enduring power.

Photo Tour

Stephansdom is located in Stephansplatz, the center of medieval Vienna. I do not recall why I have no photos of the west facade; it was likely behind scaffolding or something. But figures 1 & 4-9 show much of the exterior, including the spired south tower (figures 5-6), finished in 1433 and the north tower, left as a stub in 1511 and then capped in 1578 (figures 1, 7-8).

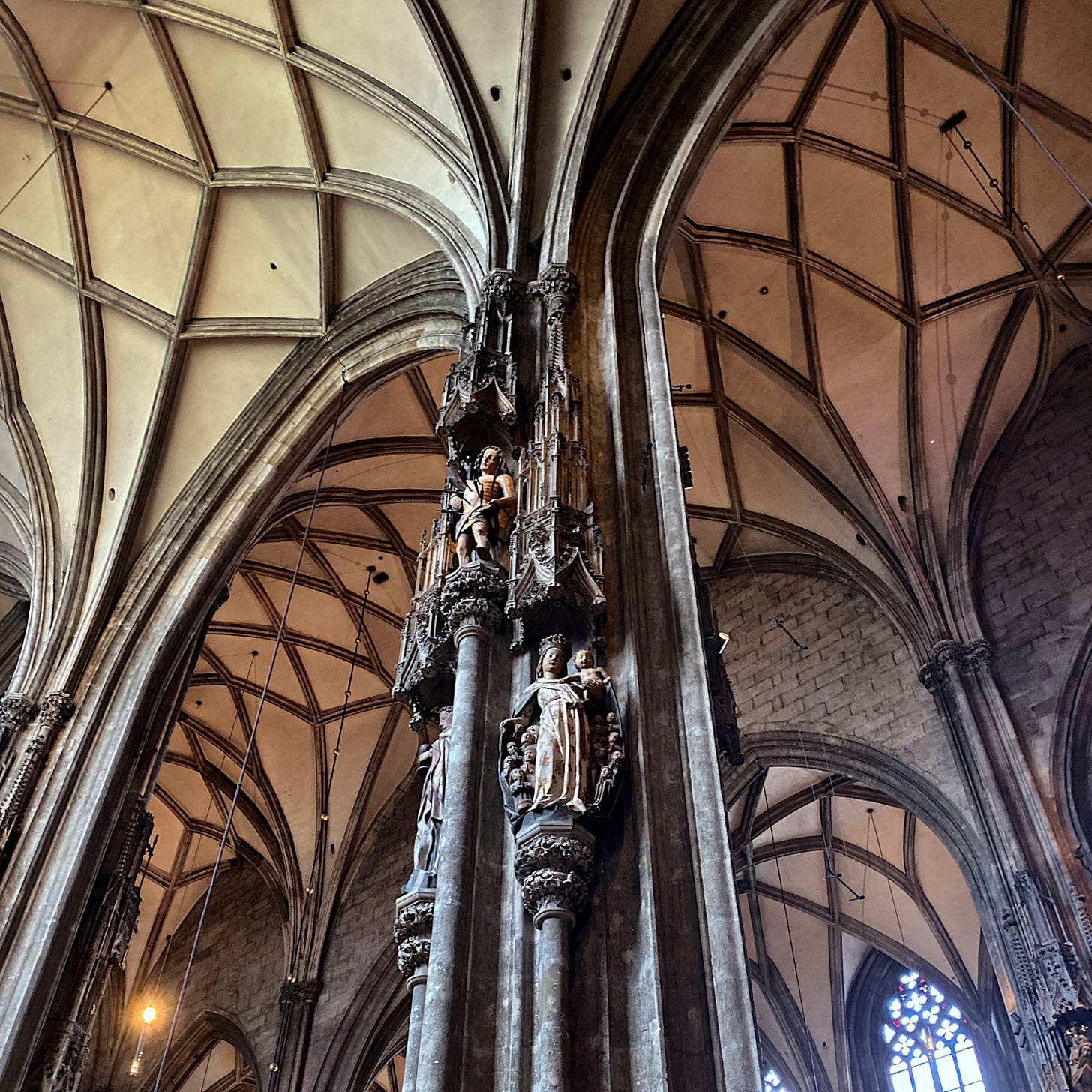

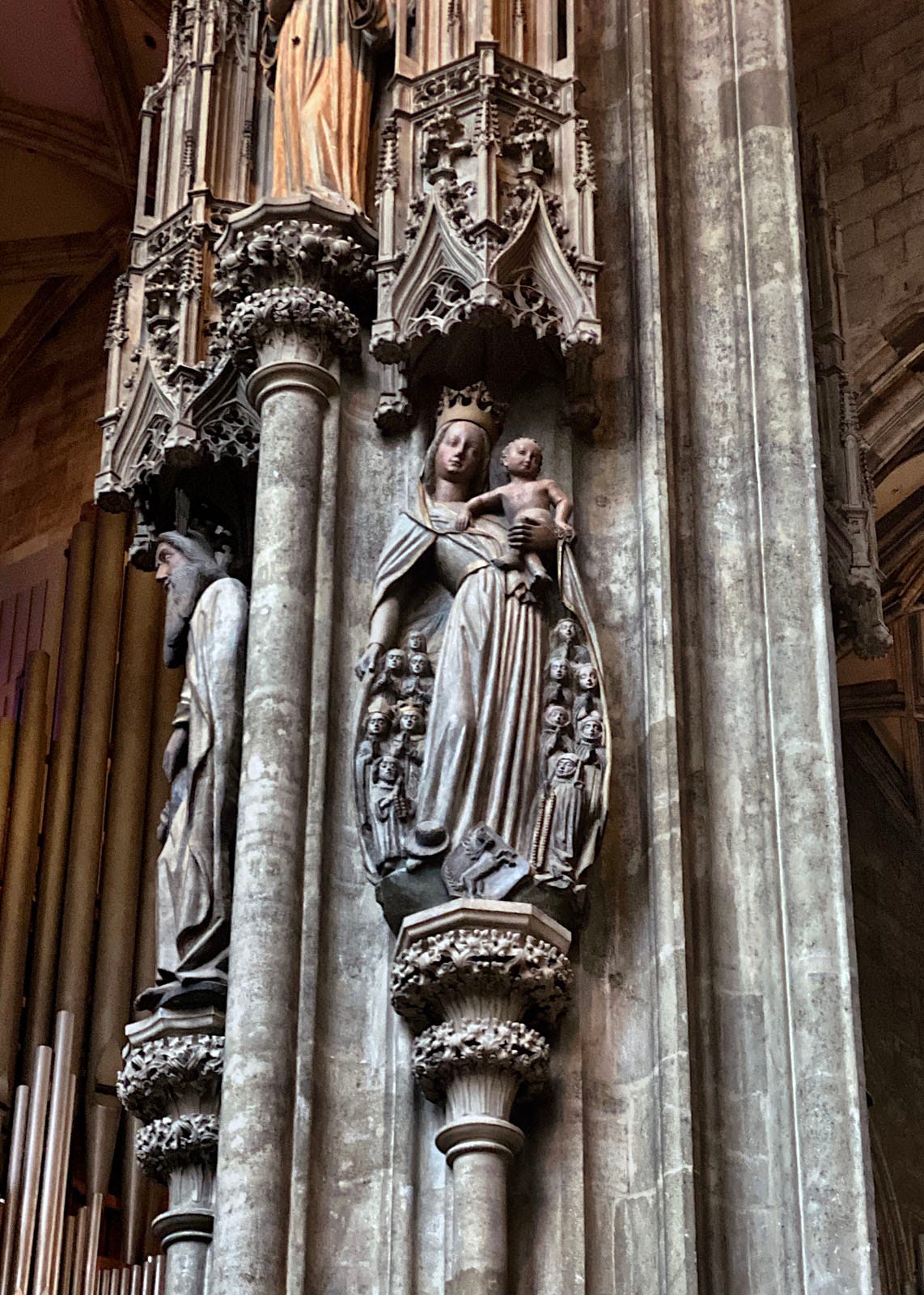

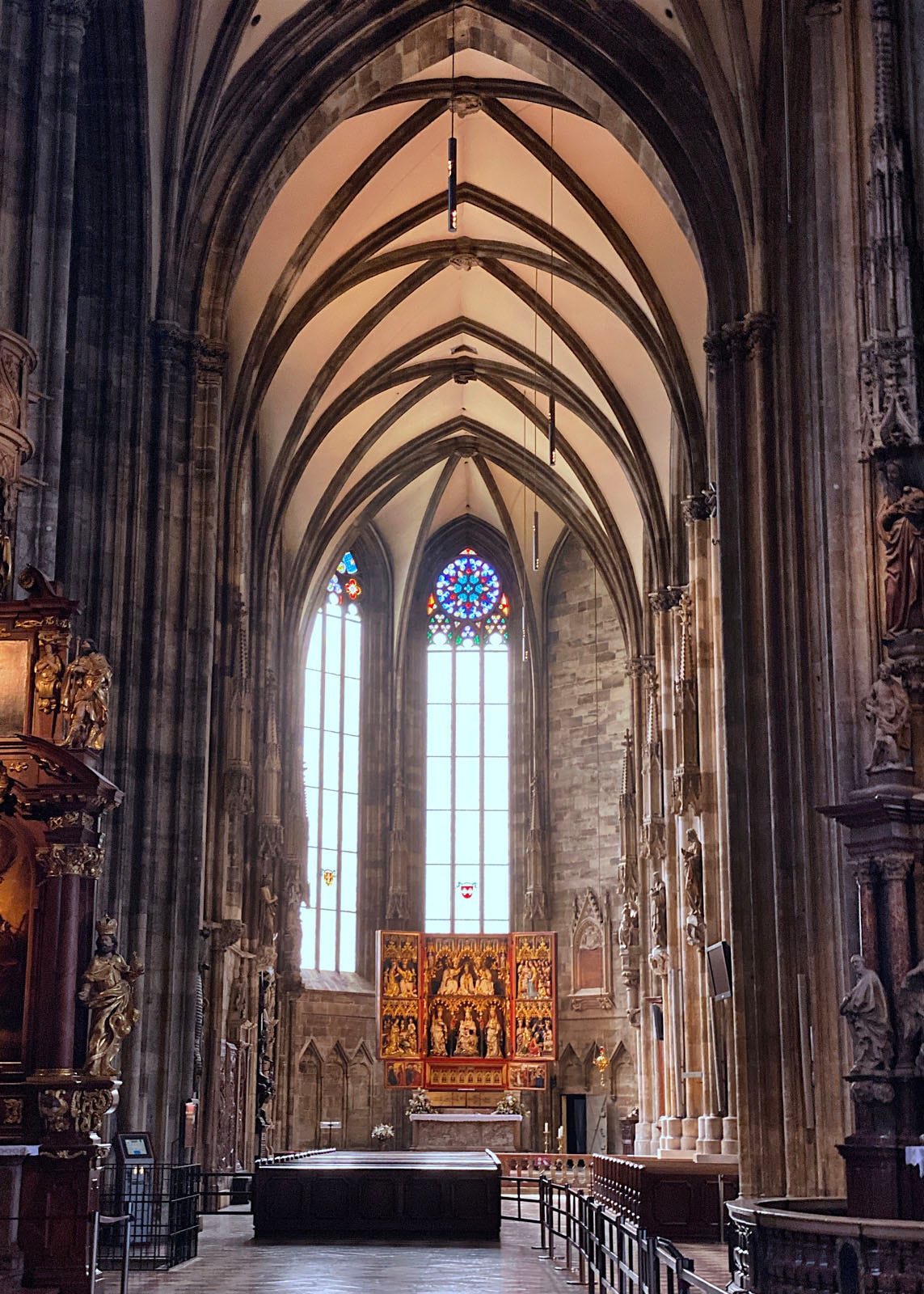

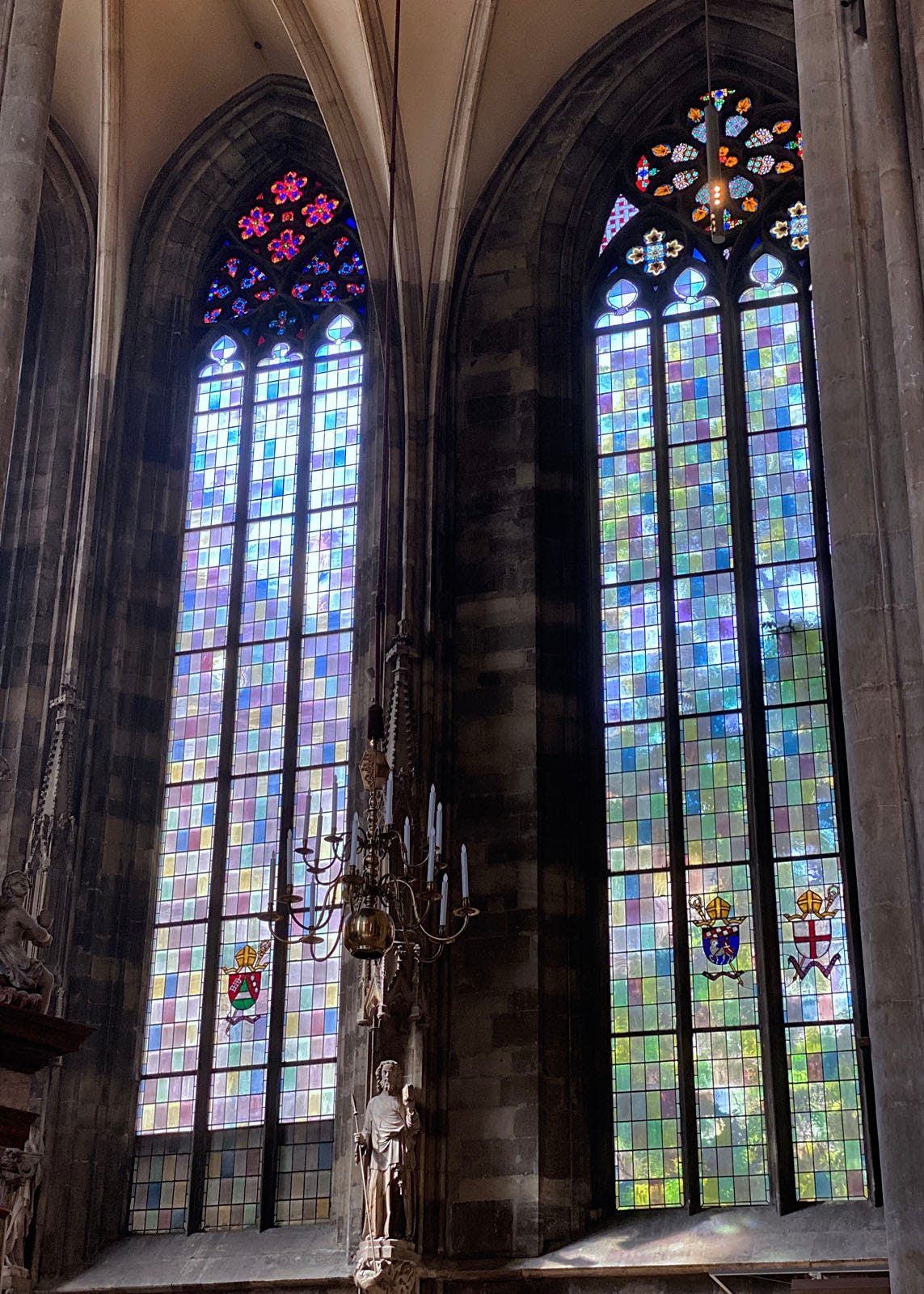

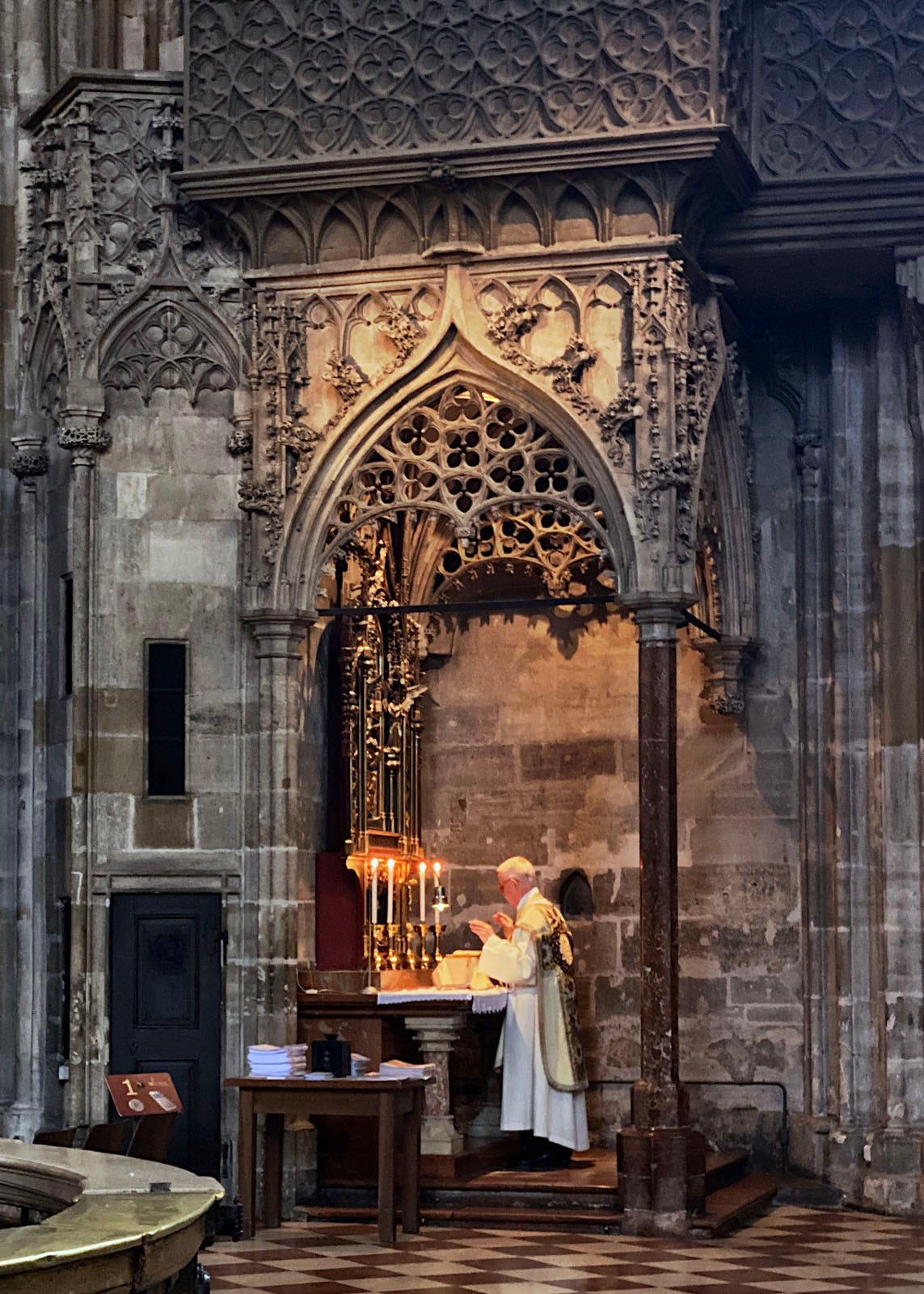

The interior of St Stephen’s (figures 2, 10-20) is very open, with large bays and high side aisles, and contains some spectacular net vaulting. The famous late Gothic pulpit (figure 13), completed around 1515, exemplifies St. Stephen’s role as a crossroads of artistic traditions. Carved by the Netherlandish master Anton Pilgram, it showcases the kind of international talent that Vienna’s imperial status could attract.

The side aisles reveal St. Stephen’s unique spatial character, where Germanic Gothic traditions created unusually open and unified interior volumes. Unlike French cathedrals with their clear hierarchical divisions, the side aisles here feel almost as important as the nave itself.

Photos 17-19 show some details. Frederick III’s tomb (figure 18) — created by Niclas Gerhaert van Leyden around 1467-1513 — represents both the artistic pinnacle of late Gothic funerary sculpture and a powerful statement of Habsburg imperial ambition.

The view in figure 20 across the side aisles and nave captures what makes St. Stephen’s architecturally distinctive: the sense of horizontal flow and visual connection between spaces that characterized mature Germanic Gothic.

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Dates: 22 & 27 June 2022

As I mentioned at the start of the essay, St Stephens has limited hours and limited public access. Entry beyond the narthex requires a ticket (which can be purchased on site), and entry into the towers, crypts and some other areas require additional tickets. It is one of the least user-friendly cathedrals I have ever visited. You may want to plan in advance and buy tickets online.

That said, Stephansdom is one of the greatest works of Gothic and no visit to Vienna would be complete without a visit to appreciate it.

I agree with your assessment of the visitor experience. The only time I visited it was so cold that I (uniquely) forgot to remove my hat, a small wool cap. Normally I remember that it's the Christian God who abhors hats and the Jewish God who abhors bare heads. As soon as I entered a repulsive little priest shoved his way through a crowd of baseball capped Americans to berate me for my act of sacrelage. 1 out if 5, would not recommend. Especially as Vienna contains so many wonderful monuments, from the Kaisergruft to the Imperial treasury.

I enjoyed this essay as I do all of yours. Excellent insights along with your photos. I was especially touched by the priest celebrating mass because it connected the history with the present.