Greatest Gothic, #26: Magdeburg Cathedral

The First German Gothic & Otto the Great’s Resting Place

(9 min read) Magdeburg Cathedral — number 26 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is not just Germany’s first Gothic cathedral, but also the burial place of Otto the Great, and home to some exceptional medieval sculpture.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Magdeburger Dom (Magdeburg Cathedral)

Official Name: Dom zu Magdeburg St. Mauritius und Katharina (Cathedral of Saints Maurice and Catherine)

Location: Magdeburg, Germany

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1209-1520

Why It’s Great

The Cathedral of Saints Maurice and Catherine in Magdeburg earns its place as one of the most historically significant Gothic buildings in Europe through a unique combination of imperial legacy, architectural innovation, and artistic achievement. More than juat Germany’s first Gothic cathedral, Magdeburg represents the intersection of political power, religious transformation, and artistic evolution across some seven centuries.

Why It Matters: History and Context

The story here starts three centuries before the Gothic cathedral was begun, when King Otto I chose Magdeburg as his palatinate residence and gave the city to his wife, Eadgyth (Edith) — grand-daughter of Alfred the Great — as a wedding present.

In 937, Otto founded a Benedictine monastery and church dedicated to Saint Maurice, intended as a burial site for his immediate family. When Queen Edith died in 946, she was buried in the church. Otto was given the moniker “the Great” when his troops defeated the Magyars in 955, and in the same year he commissioned an imperial basilica at the monastery site.

In 962, Otto was crowned Holy Roman Emperor, becoming the first German king with the title. In 968, he selected Magdeburg as the seat of an archdiocese, making the basilica a cathedral. Otto died in 973, and was buried in the cathedral next to his wife.

The Ottonian cathedral was destroyed on Good Friday in 1207 by a city fire. The archbishop at the time, Albrecht von Kaefernburg immediately tore down the few surviving walls, as — having seen the Gothic churches now being built in France — he wanted a completely new and “modern” church.

The result was the first Gothic cathedral in Germany. As there were no previous examples of Gothic architecture in Germany, and German craftsmen were still very unfamiliar with the style at the start of construction, their progress can be seen in small architectural changes over the construction periods. Construction began in 1209 and continued for over three centuries until completion of the steeples in 1520.

Much of the eastern end is in a late Romanesque/proto-Gothic style, but by 1235 — under Archbishop Wilbrand — the Gothic influence increased considerably.

The building process was neither smooth nor uncontroversial. As construction was supervised by different people over 300 years, many changes were made to the original plan, and the cathedral size was repeatedly expanded.

Construction stopped in 1274 for several generations, began again after 1325, and was then halted in 1360. Not until 1477 did construction restart this time around, and in 1520 — with the finalization of the west facade’s north tower — the cathedral was finally complete.

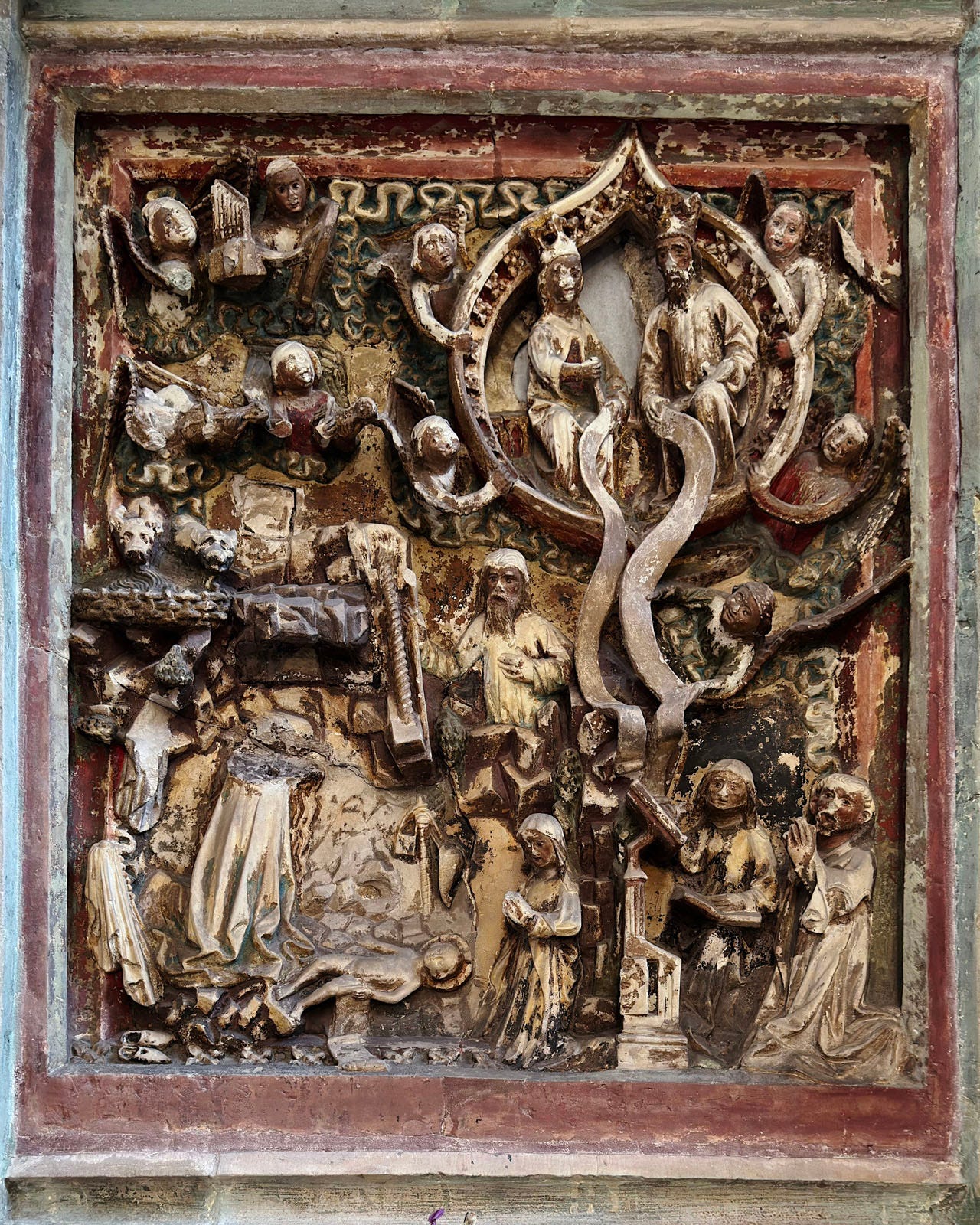

What emerged from this protracted construction was not merely Germany’s first Gothic cathedral, but one of its most artistically interesting. The cathedral’s sculptural works (figures 1, 5, 10, 27-30 and “In Detail” below) are exceptional and include works from late antiquity and Ottonian times integrated into the Gothic fabric, as well as Gothic sculptures made as the present cathedral was being built. Particularly important are the mid-13th century sculptures, including a statue of St Maurice (the first depiction of a Black African in central European sculpture), and a skillful portrayal of the Wise & Foolish Virgins.

In 1524, Martin Luther came to Magdeburg at the request of Mayor Nicolaus Sturm and preached to overwhelming crowds. On 17 July 1524, nearly all of the city’s churches committed themselves to Lutheranism and the Catholic Mass was abolished. Magdeburg gained a reputation as a stronghold of Protestantism and became the first major city to publish the writings of Martin Luther, earning the nickname “Our Lord God’s Chancery.”

This Protestant identity proved catastrophic during the Thirty Years’ War — in 1631, Magdeburg was sacked and only a small group of 4,000 citizens survived, seeking refuge in the cathedral. However, as the Catholic forces left Magdeburg, the cathedral was completely looted, losing stained glass, much art, and (likely) the grave goods in Otto’s tomb.

Between 1826 and 1834 Frederick William III of Prussia financed much needed repairs and reconstruction; these were overseen by Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

Magdeburg Cathedral saw a lot of damage during World War II as well, though it remained intact. All of the windows were destroyed over the course of frequent area bombings, and on January 16, 1945, a firebomb hit the cathedral, destroying the west facade and the organ. Magdeburg fell under Soviet control in 1949, but despite communist leaders’ efforts to suppress religious activity the cathedral was re-opened in 1955.

Reconstruction efforts began in 1983 and are still ongoing, though they do not substantially detract from a visit.

Photo Tour

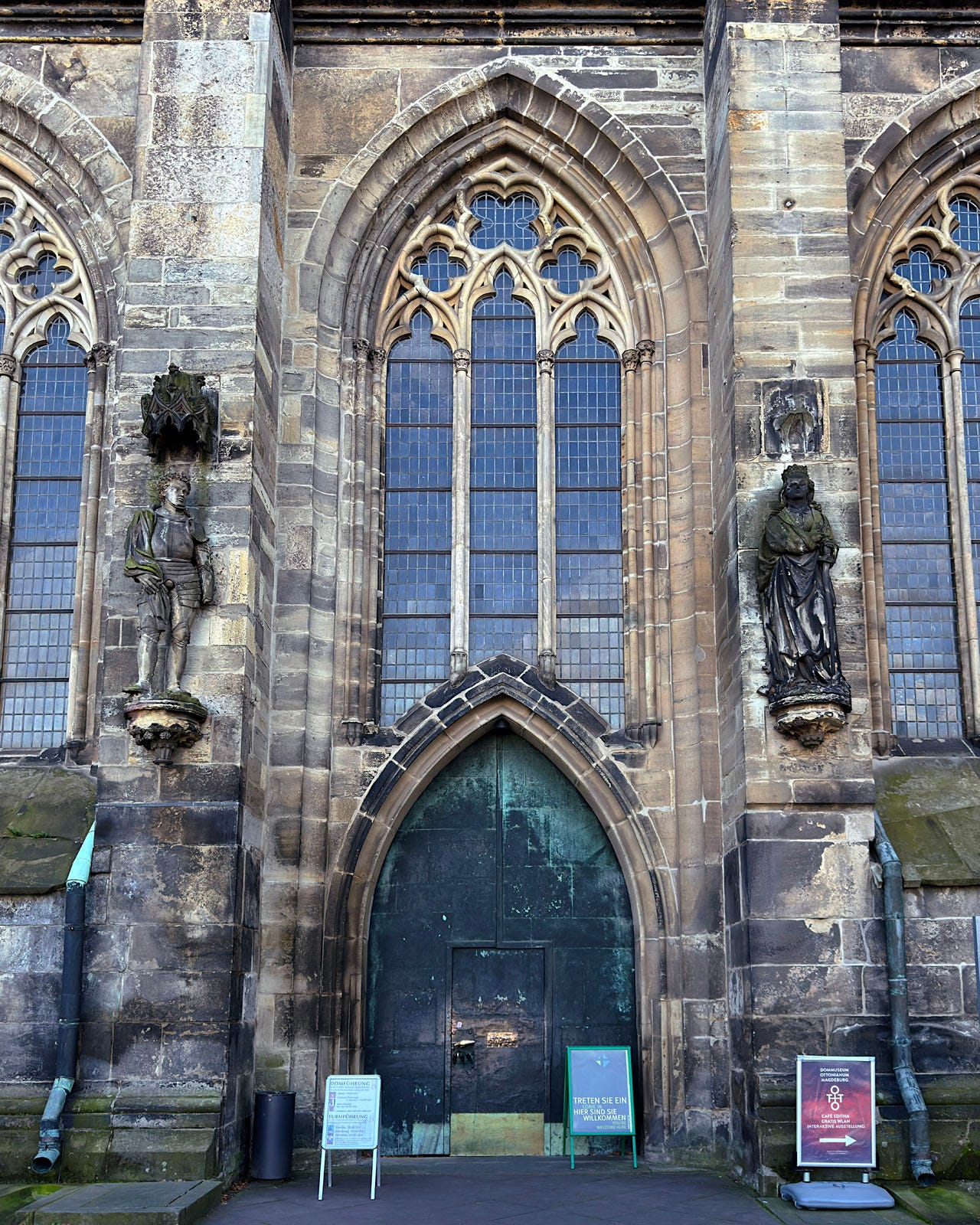

Magdeburg is surrounded by a car park to the north, cloisters to the south, and a large plaza — complete with labyrinth (figure 8) — to the west. Entrance to the cathedral is on the north side (figure 10), for reasons that become apparent when you visit the narthex (figures 11-12).

On the ground floor in between the towers is the narthex (figures 11-12), where a tomb was built in the early 16th century for the bishop at the time. It is gated

The soaring nave (figures 2, 13-15) is exceptionally light-filled, with large clerestory windows and verticality emphasized by the clean lines of the columns and arches. The baptismal font has a central location in the western end, and is a piece from late antiquity, brought here in Ottonian times.

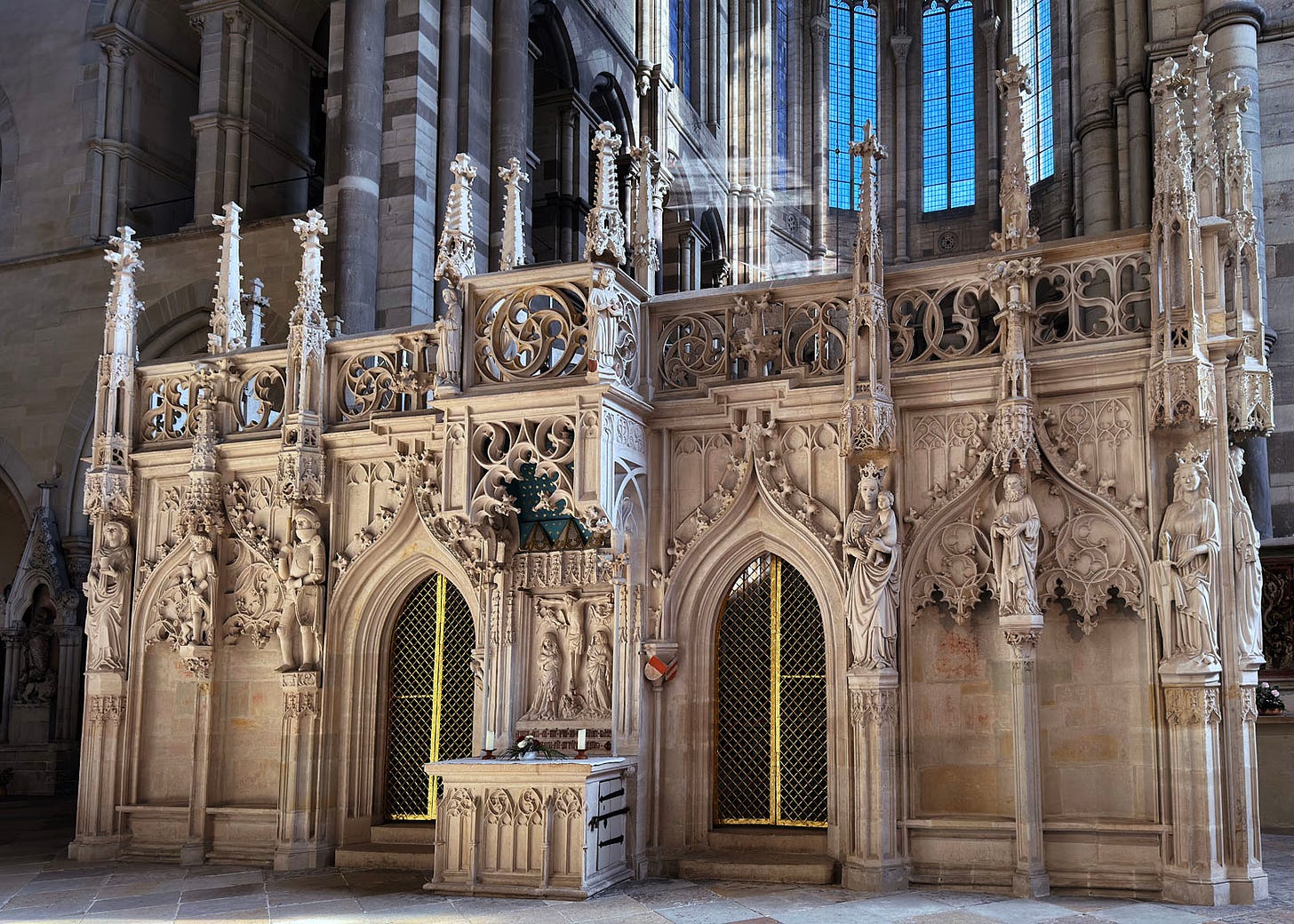

The chancel contains the tomb of Otto the Great (figures 17-18), as well as an exceptional array of stone sculptures in the apse triforium (figures 1 & 17, “In Detail” below) and a fine set of choir stalls and misericords (figure 19 & “In Detail” below).

Both the chancel and the ambulatory (figures 20-23) were the earliest parts of the church to be built and in a transitional Gothic style, with Romanesque carvings in the capitals (figure 21 & “In Detail” below) and heavier forms than the nave and side aisles, though with similarly clean lines and styling.

The cloister (figures 4, 24-27) is to the the south of the cathedral, and contains the only portion of the previous cathedral still standing — the southern arcade (figure 24).

There is a late Gothic chapel built off the side of the northern arcade (figure 27), which is notable for two reasons. One is the skeletal “flying ribs” holding up the ceiling, a feature I have only otherwise seen — so far as I can recall — in St Mary’s Warwick (UK). The other is a very modern and moving Crucifixion, made of bronze in the 1980s.

As I mentioned in the main section above, Magdeburg is home to a lot of great sculpture. I have described and shown much of the more “integrated” sculpture — column capitals, jamb and apse figures — above and in the “In Detail” section below. But figures 28-30 show just a few samples of the photos I took of more “random” sculptural pieces I found while wandering around the building complex.

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

In Detail

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 23 October 2024.

A visit to Magdeburg Cathedral reveals the complex forces that shaped medieval and early modern Europe. It remains the burial place of the first German Holy Roman Emperor, the first Gothic structure built on German soil, and home to several significant sculptural programs.

Entry is free but there is a nominal fee to take photographs.

There is also a small but informative museum across the square (the “Dommuseum Ottonianum Magdeburg”). Labeling is largely in German only, but if you want to know more about the history of Ottoman Magdeburg and the present cathedral, it is worth a visit after your time in the cathedral. (I show a few pieces from the museum in the final embedded Note in the “In Detail” section above.)